February 18, 2018Designer Ghiora Aharoni opened his eponymous design studio in 2004, after stints with Polshek Partnership Architects (now Ennead) and Daniel Libeskind (portrait by Beowulf Sheehan). Top: His own open-plan apartment combines living and dining rooms in one 50-foot-long space (photo by Belén Imaz).

Ghiora Aharoni is soft-spoken and moves through life with poise. At the same time, he is willing to upend tradition.

As a boy in Israel, Aharoni studied Jewish texts with his grandfather. Now a New York–based interior designer with a knack for creating soulful spaces, he is also a frequent creator of text-based art. As part of his Hebrabic series, Aharoni devised a modified version of a traditional daily prayer that men say: “Thank God for not making me a woman.” He changed it to “Thank God for making me a woman” and had a calligraphic version cut into a block of stainless steel to form a sculpture. Several versions are on display in his Manhattan studio, as are many other pieces for which texts provide both concepts and physical forms. For Aharoni, words don’t just express ideas — they’re a material.

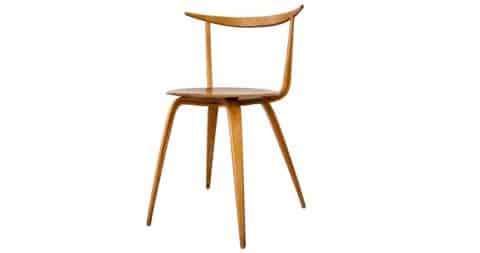

As an interior designer, Aharoni is working on projects as varied as an international tech firm’s headquarters in Manhattan, a gallery in Tokyo, and several New York apartments. Some of them will contain furniture and objects he designed, but he doesn’t insist on it. His own home, in the West Village, features a Finn Juhl sofa, George Nakashima dining chairs and a pair of lithographs by Robert Longo. Aharoni made a point, he says, of selecting items “that relate either through form or material, creating conversations.”

The place to get a sense of Aharoni’s varied output is his Fifth Avenue studio. Hanging high overhead are several ribbon-like sculptures, resembling bits of calligraphy that have flown off the page. “I am trying to portray language in three dimensions,” Aharoni says of the wood-and-plaster pieces. Elsewhere is a group of seven dramatic glass assemblages, each representing a day in the Old Testament story of creation. Aharoni etched biblical passages onto vintage chemistry lab glass (flasks, beakers, tubes); infilled the words with black ink; juxtaposed the glass elements with 18th- and 19th-century Torah finials from Yemen, Iraq and Morocco; then connected all the elements with laboratory rods and clamps. Imagine a shimmering glass bouquet on a steampunk armature, and you’ll start to get the picture.

Some of Aharoni’s objects are clearly art. Others are functional, such as his Deco-inspired Jobim 276 coffee table, made of powder-coated steel and wire glass. Still others are uncategorizable, like his “Hyper-Cubes,” a series of unique pieces inspired by the concept of the fourth dimension, where, he says, “space and time are unified.” He explores that possibility by placing a black walnut cube (divided into halves that could be trays or drawers) within a larger cube of metal. “The blur between art and design is what I love,” says Aharoni.

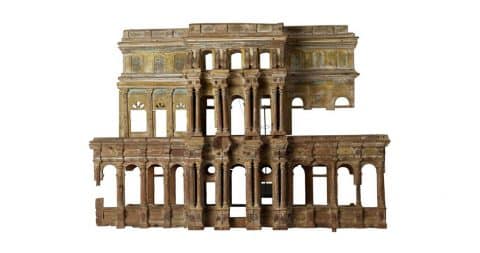

In Aharoni’s light-filled open-plan Fifth Avenue studio, a quartet of his “Rondolinear” sculptures hangs high on the white wall above the work stations. Under the mezzanine sit artworks from the same series as those in his installation piece the The Road to Sanchi, currently on view at New York’s Rubin Museum through October 15. Photo by Avid Bar-Ness

The Road to Sanchi is composed of a series of glass-domed pedestals holding vintage Indian taxi meters that Aharoni rewired with small screens. These show videos he shot on his journeys to holy sites on the subcontinent. Photo by Avid Bar-Ness

The descendant of Yemeni Jews, Aharoni grew up near Tel Aviv. His grandfather taught him to read at an early age, then introduced him to the central texts of Jewish mysticism. He left Israel at 21 to study at the City University of New York. From there, he went to architecture school at Yale, which led to jobs with Polshek Partnership Architects (now Ennead) and Daniel Libeskind. But, he says, “I wanted to have the studio I’ve always dreamed of, where I can tackle all the disciplines I adore.” He opened Ghiora Aharoni Design Studio in 2004 and in 2012 moved to the Fifth Avenue space, which features spectacular views of the Empire State Building through a large skylight.

His textual interests go beyond Hebrew. Since his student days at Yale, Aharoni has been creating a language he calls Hebrabic, in which Hebrew and Arabic characters are intertwined, with the lighter, longer Arabic strokes providing a counterpoint to the somewhat blockier forms of Hebrew. Each sculpture is composed of a phrase — such as “Let my people go” — in Hebrabic. More recently, as part of his exploration of India (a country he has visited 20 times in 14 years), Aharoni created a similar melding of Urdu and Hindi, called Hindru, which presented an additional challenge as Urdu is read from right to left and Hindi from left to right.

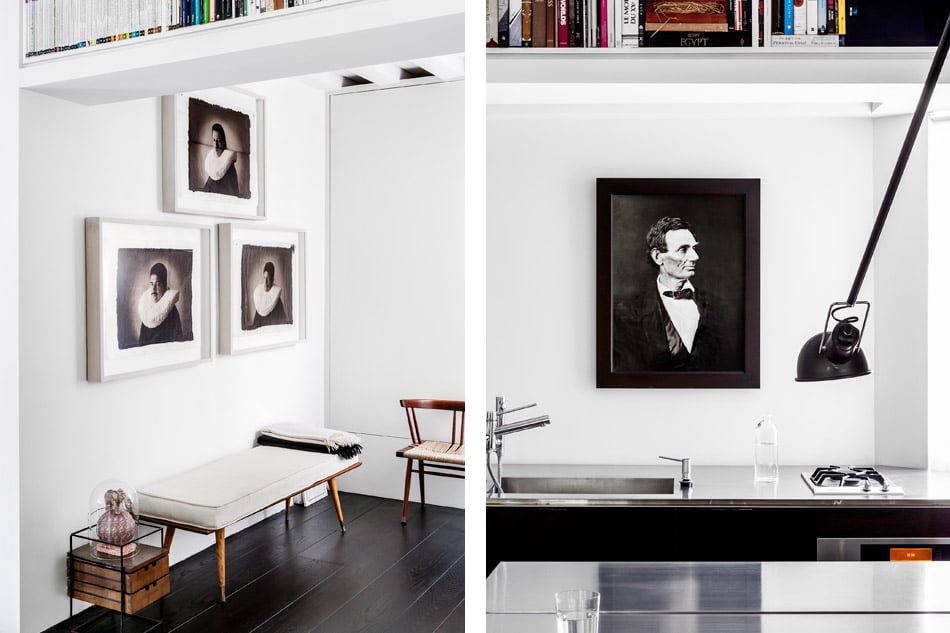

But Aharoni thrives on design problems. His own apartment was formed by joining two small units; the resulting living room has eight large windows. “You open the door, and it’s a shock,” he says of the contrast between the tenement building’s modest exterior and the wonderland he created inside. He revealed the apartment’s turn-of-the-century roots by exposing brick walls, ceiling beams and wooden studs that had been hidden behind plaster. By painting everything white, he was able to meld those rough materials into a minimalist contemporary backdrop. To make the 1,100-square-foot space flow, he opened up the kitchen (avoiding upper cabinets and full-sized appliances), and outside each window, he installed planters, now filled with evergreens and ivy, to extend his domain beyond the apartment’s four walls.

“I wanted to have the studio I’ve always dreamed of, where I can tackle all the disciplines I adore,” says artist and interior designer Ghiora Aharoni.

Uptown, Aharoni recently turned an apartment in a late-1930s building into an ethereal, otherworldly oasis. After gutting the unit, he rebuilt it with as few surfaces as possible, and he covered these in as few materials as possible, for maximum aesthetic continuity and calm. White oak, gently illuminated by cove lighting, was used for floors, walls and ceilings. Lithographs by the Indian artist M.F. Husain were installed in a long row above an equally long row of low USM Haller storage units, emphasizing the horizontal sweep of what had once been a conventional apartment.

In one of the two living areas in Aharoni’s own apartment, a Finn Juhl sofa and chairs sit under works from Robert Longo’s “Men in the Cities” series. Photo by Belén Imaz

In Chelsea, Aharoni created a pied-à-terre for a client who, he says, asked for a “complete work of art, a Gesamtkunstwerk.” Inspired by the building’s exterior details, he responded with a streamlined Deco interior. First, he removed most of the walls; then, he converted the right angles where the remaining walls meet the ceiling into curves. The continuous flowing lines create a sense of movement that expands the perception of the space, he says.

Most strikingly, he covered the upper half of the apartment in hand-applied silver leaf and the lower half in oak — mirroring, he says, “the magnificent dialogue between the earth and the sky, the terrestrial and celestial.” The celestial is particularly stunning: The shimmering silver leaf ceiling makes the space seem infinite, he says. But he didn’t neglect the terrestrial. He chose the widest oak boards he could get for the floors, their dimensions “subtly extending the sensation of space.”

Even this Gesamtkunstwerk contains pieces by other designers. Aharoni placed Mies van der Rohe dining chairs around an Angelo Mangiarotti table, also selecting a Vladimir Kagan Swan sofa, a Zig-Zag chair by Gerrit Rietveld and artworks by Richard Serra. “I would never think to do everything myself,” says Aharoni. His designs are about connections between times and places.

As is his art, which includes the The Road to Sanchi, an installation on view at the Rubin Museum of Art through October 15. Aharoni shot videos of his travels in India to places sacred to several major religions — including Sanchi, where a giant stupa rests on relics of the Buddha. The videos are displayed on small screens inserted by Aharoni into vintage taxi meters that he collected in Indian cities. The meters themselves are compelling objects, their relative crudeness making the images shown on them seem other-wordly. The resulting installation — 12 of the meters are set on pedestals under glass domes — is a compelling meditation on life’s journey: Aharoni deliberately shows only the pilgrimages, not the destinations.

Ghiora Aharoni’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs