October 25, 2020When Pierre Guariche announced to his parents in 1946 that he wanted to study design, they were less than thrilled. His mother and father had him undergo a “psychotechnical” exam to assure them, he recalled in an interview in the late-1960s, that “firstly, I was not out of my mind, and then, that I was fit for such activities.”

In retrospect, they need not have worried.

Guariche went on to become one of the most successful French designers of the postwar period. Today, he is best known for his furniture and lighting. Incredibly prolific, he created some 60 different light fixture models in the 1950s alone. One of the first was a floor lamp, which Charlotte Perriand used in a private interior she was creating. The two designers were both represented by MAI at Saint-Germain-des-Prés, a gallery whose roster included such other notable mid-20th-century names as Pierre Jeanneret, Alvar Aalto, and Gino Sarfatti.

In parallel to his work creating furnishings, Guariche had a decades-long career as a highly sought-after interior designer. His commissions ranged from apartments in Paris and residential resort development on the French Riviera to a ministerial building in Cameroon and countless corporate headquarters.

Guariche was entrusted with completing Le Corbusier’s Maison de la Culture, an arts complex in Firminy-Vert, to the southwest of Lyon, after the great man’s death, in 1965. He also spent some 15 years working on the La Plagne ski resort in the French Alps, where his interventions included outfitting apartments, a bank and a chapel as well as imagining a series of wonderfully sleek, cube-like cable cars.

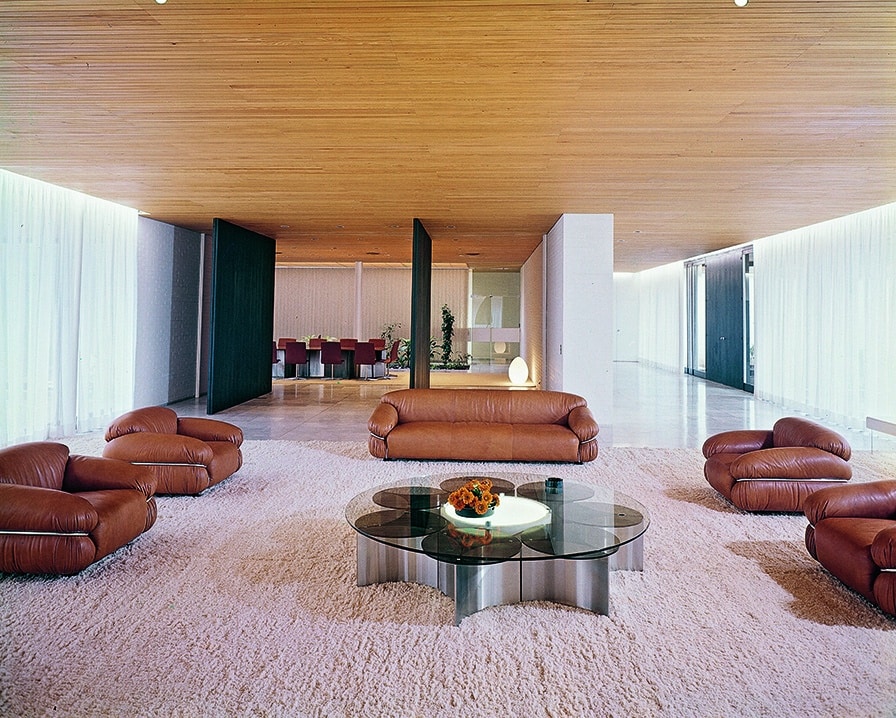

In the large reception room in the prefect’s residence of the Préfecture de l’Essonne — an administrative building from the late 1960s in Évry, south of Paris — Guariche used Oregon pine for the ceiling and slabs of white marble for the floor. To these, he added Tobia Scarpa Soriana sofas and armchairs and a large stainless-steel and smoked-glass coffee table. The apartment’s dining room can be seen in the background.

Guariche, who died in 1995, has not received the same acclaim as his contemporary Pierre Paulin, born just a year earlier and a far better self-promoter. In recent years, however, Guariche’s work has been gaining increasing traction with discerning tastemakers, such as interior designers Robert Stilin; Julie Hillman; and Alexandra and Michael Misczynski, of Atelier AM.

And now, a wonderfully detailed and comprehensive new monograph, Pierre Guariche (Norma Editions), is sure to bring the designer to the attention of a much wider public.

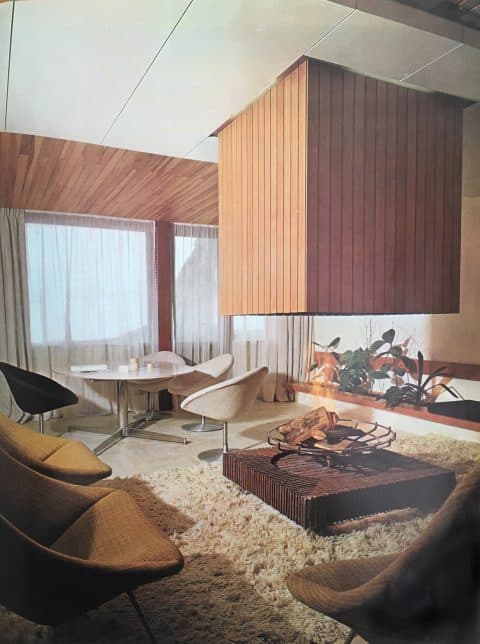

In the 1960s, Guariche designed the interiors of vacation apartments, including this studio, in a complex by architect Jean Dubuisson in Bandol, on the French Riviera.

There is nothing superfluous in the work of Guariche, who adhered firmly to the “form equals function” school of thought. The beauty and appeal of his pieces lie in their interplay of lines and shapes, and the quest they embody for ever-simpler forms.

“I think he’s an incredible designer,” says Hugues Magen, of Manhattan’s Magen H Gallery. “I love the rationality of his lines. Everything became extremely essential.”

Guariche’s work feels almost utopian, not far removed from the modernist, Technicolor world of Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle. “He had a sort of mission to bring good taste to the French household,” notes interior designer Hugues Disderot, whose father, also named Pierre, produced Guariche’s lighting. In the early part of his career, at least, Guariche had Communist leanings and a desire to create a better world for the masses.

That didn’t prevent him, however, from later leading a relatively bourgeois life and driving a bright red Porsche 911.

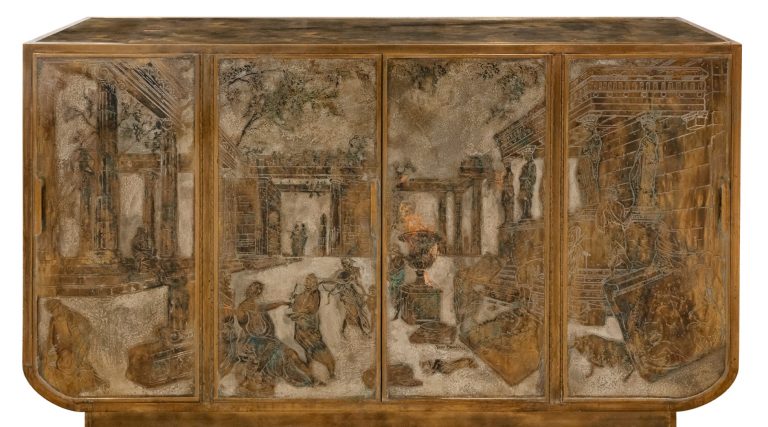

A looser, even louche, Guariche is on display in the reception area of the Hôtel Méridien on the Boulevard Gouvion Saint-Cyr in Paris, which he designed in high glam style between 1970 and 1971.

Guariche was born on June 6, 1926, in Bois-Colombes, a suburb to the west of Paris. He studied engineering before enrolling at the École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, in Paris, graduating in the same year as another postwar French design star, Alain Richard.

A pair of collaborations defined the next chapter of his career. In 1954, Guariche set up a design collective called ARP (Atelier de Recherche Plastique) with a pair of school friends, Michel Mortier and Joseph-André Motte. The venture lasted three years, during which time the partners worked on numerous interiors projects and produced some 30 furniture designs. Then, in 1960, the furniture company Meurop appointed Guariche as its art director.

At the height of its success, the Belgian firm had some 6,000 employees and 42 showrooms in six different countries. Its aim was to make well-designed pieces accessible to the masses — or, as Guariche quipped in an interview in the late-1960s, “to mass-produce good-taste furniture at the price of bad-taste furniture.” He designed for Meurop until 1972.

Through ARP (Atelier de Recherche Plastique) — a collective he set up in 1954 with two friends from design school, Michel Mortier and Joseph-André Motte — Guariche created this interior for the magazine La Maison française in 1955. It features a sofa composed of his G2 seats and a desk chair by Harry Bertoia.

According to Aurélien Jeauneau, one of the new book’s coauthors, the pieces Guariche designed for Meurop represent his “modernist manifesto,” and are the most interesting part of his oeuvre. While at the firm, “he created a vast diversity of different types of furniture,” Jeauneau explains, “and he pushed the purification of forms to the limit.”

This quest for purity is exemplified by the rectilinear Nathalie daybed and Robert chair, the latter slightly reminiscent of the work of Jean Prouvé, with its leather-clad seat and wooden armrests.

This virtuosic marrying of function with refined form characterizes pieces from throughout the designer’s career. Matthijs Hoveijn, founder of the Dutch gallery Morentz, is a fan of Guariche’s lighting in particular. With those, “he created something fresh, new and interesting,” the dealer says. “You really feel movement in his lamps.”

Nowhere is this more evident than in Guariche’s most iconic design — his G23 floor lamp from 1953, whose pair of pendulum-style arms are masterfully arranged in a precisely calculated equilibrium that allows them to be positioned at different angles and heights. The two sheet-metal shades — one larger and fitted with a perforated reflector —produce different types of light: direct and indirect. The lamps currently sell for about $42,000.

Also sought after is Guariche’s rotating Kite sconce, model G25, whose gently crimped white deflector seems almost to float in the mid-air, and his rare chair designs. Among these are the Vallée Blanche chaise, designed in 1963 with an elegantly reclined seat supported by a spiky chromed-metal base, and the wingback Prefacto model, originally part of a series of furniture with metal-tube frames that he imagined for the French firm Steiner.

Guariche’s aesthetic is remarkably consistent throughout the 1950s and ’60s, at least in part because he rolled out several variations on particular designs. One spread in the book juxtaposes the Tonneau, Amsterdam and Tulipe chairs. The family resemblance is striking: The models all have similarly shaped tapered backs, each sporting an oval cutout.

Starting in the early 1970s, Guariche turned his back on furniture design and devoted himself almost exclusively to interiors. Some of his projects, such as small studio apartments in La Plagne, show him as a master of both economical and space-saving solutions. He favored versatile modular furniture and astutely created 180–square-foot dwellings that could sleep up to five

Other interiors have a sassier look, with splashes of orange and carpeted walls. His own apartment in Paris’s 15th arrondissement featured Paulin’s Little Tulip dining chairs, plus a sofa and two armchairs from Gianfranco Frattini’s Sesann collection.

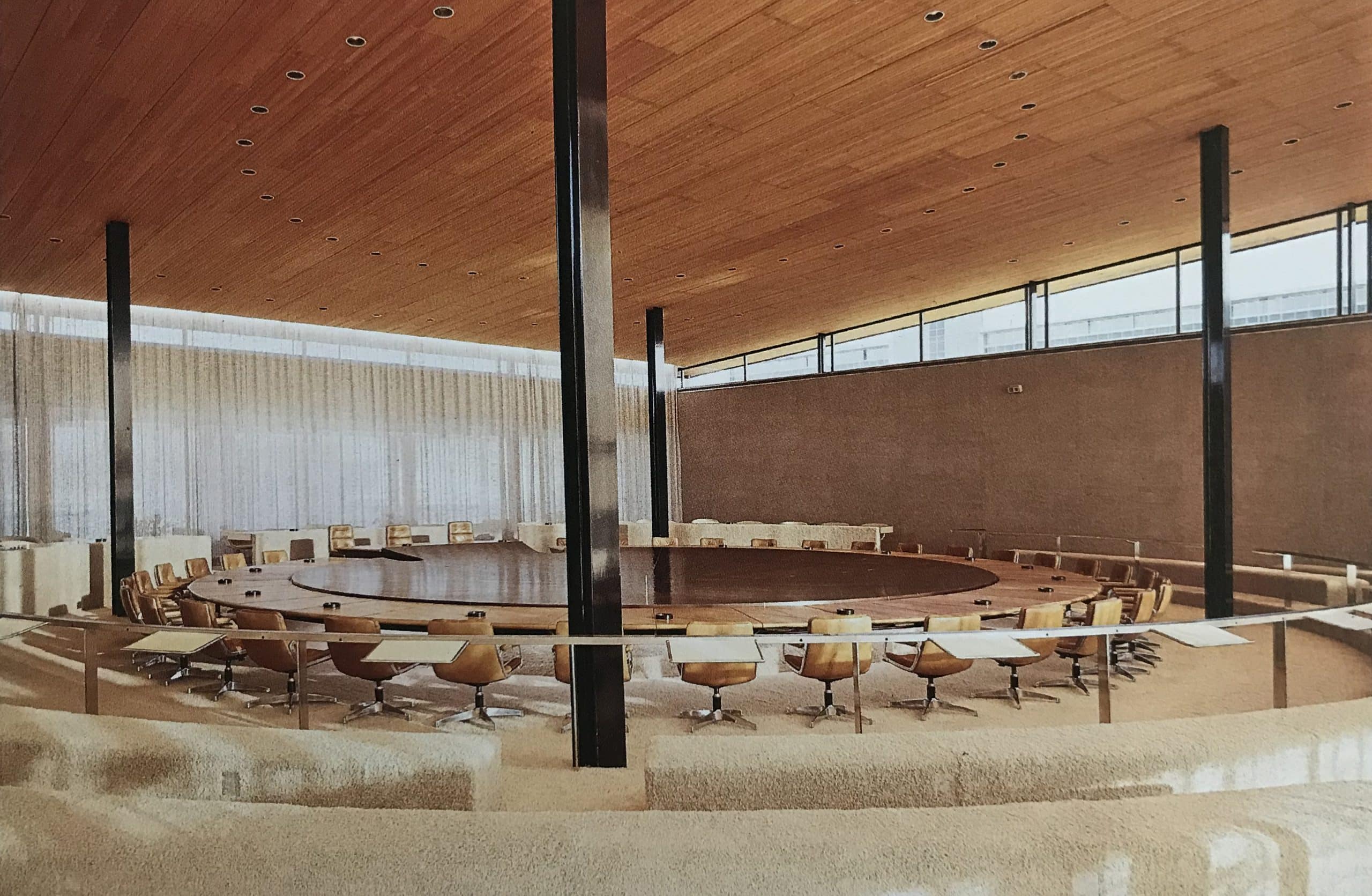

But his most majestic interior may well have been that of the Préfecture de l’Essonne, an administrative building designed in the late 1960s by architect Guy Lagneau in Évry, to the south of the French capital. Although the structure remains standing, the Guariche interiors unfortunately no longer exist. If they did, they would make a perfect setting for a James Bond film.

The book contains captivating images shot soon after the building opened. The plenary hall is dominated by a huge ring-shaped table clad in leather, and the prefect’s apartment has a sunken pit in the living room and furniture by the likes of Paulin, Poul Kjærholm, Charles and Ray Eames and Eero Saarinen.

Strangely, Guariche regarded himself as neither designer nor decorator. “I would consider myself rather to be a mini city planner,” he once said. According to Hugues Disderot, he called himself an architect to the end of his career, despite having built only three houses.

“He loved hanging out with architects,” says Disderot. “I guess he must have had a kind of complex.” For Jeauneau, meanwhile, Guariche was quite simply a man of his times: “He captured the spirit of his era. He never looked back and never stood still. In that sense, he was a true modernist.”