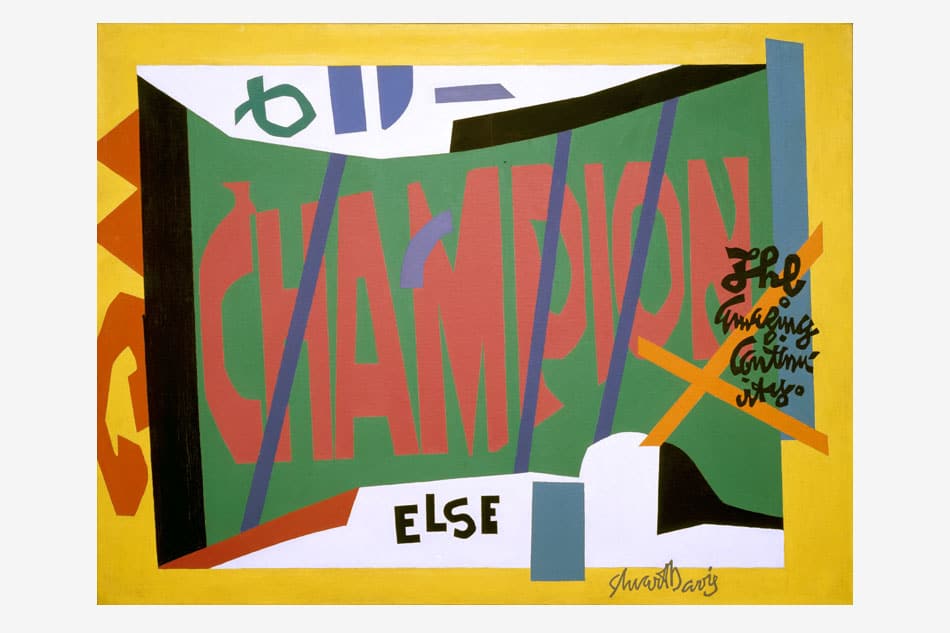

May 8, 2017In its latest stop, the retrospective “In Full Swing” brings works by 20th-century American abstract painter Stuart Davis — seen above in his studio in 1947 — to San Francisco’s de Young Museum, where it will be on view through August 6. Top: Egg Beater No. 2, 1928. All images courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

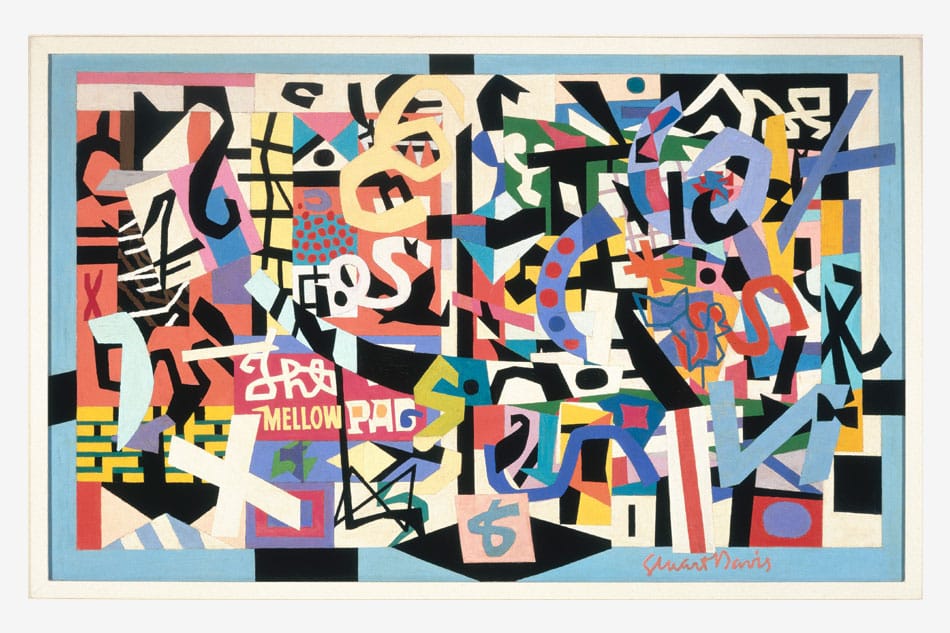

The exhibition “In Full Swing” lives up to its title. It swings with energy — the energy of the paradigmatic American modernist Stuart Davis. Lent by premier institutions including the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the 100 or so stunning and art-historically significant works have been smartly curated by Barbara Haskell, curator of the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Harry Cooper, the National Gallery of Art’s modern art curator.

The show opened at the Whitney last summer, headed to the National Gallery at the end of the year and is now at the de Young, in San Francisco, where you can catch it until August 6.

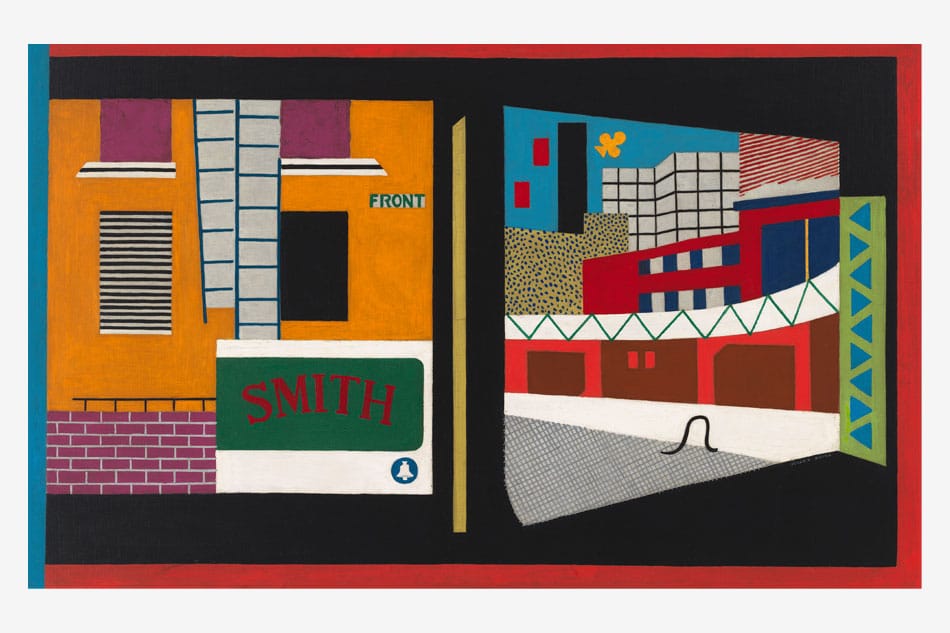

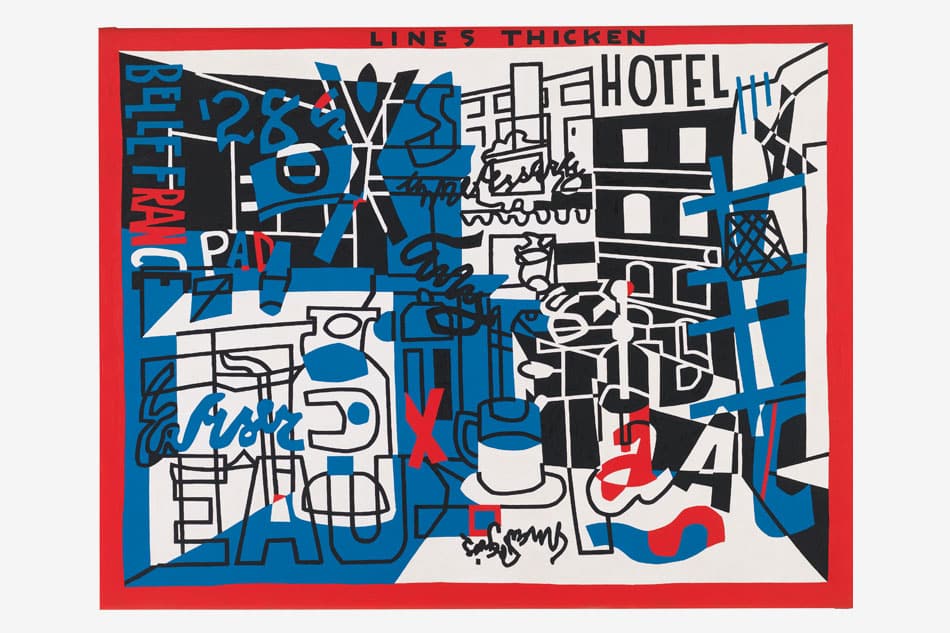

Davis was born in Philadelphia in 1892 and left high school there to study in New York with Robert Henri, whose Ashcan School must have appealed to Davis’s taste for gritty docks and city thoroughfares. His watercolors were displayed in the 1913 Armory Show beside pieces by the likes of Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp and other European modernists, who inspired his own artistic development with their assertion that neither color nor form was beholden to observed reality. After a 1928 trip to Paris, Davis returned stateside, hit full stride in the ’30s and represented the U.S. in the prestigious 1952 Venice Biennale. He became quite famous and remained active until his sudden death, in 1964.

The exhibition brings together around 100 works from Davis’s half-century-long career.

Salt Shaker, 1931

As those dates indicate, Davis’s career spanned 50 years of wonderfully complex historical events and individuals that shaped American identity, from New England fisherman, to waves of immigrants, to the Civil Rights movement, to the death of Camelot, to Pop art, to Club 57, to The Beatles’ British invasion. In weird and absolutely terrific ways, his art anticipated and embraced all of this.

Davis was one of a handful of Americans — along with Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz and Arthur Dove — who bravely carried the modernist banner in a pre-1950s, pre–Jackson Pollock America that was more at home with good ole no-nonsense realism. To be sure, he fell under the sway of European abstraction, but more thoughtful curatorial projects like this major traveling overview, as well as “Path to Abstraction,” at New York’s Hirschl & Adler last spring, reveal work that’s adventuresome and multi-sourced.

Hirschl & Adler associate director Tom Parker reminds us that Davis was no simple Europhile. Yes, Henri Matisse, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin shocked his realist roots, and Paris taught him abbreviated form, but a trip to Cuba and an extended stays in Gloucester, on the coast of Massachusetts, watching the thick seas, just as surely inspired his saturated colors and use of light. “Even in his most abstract works, Davis worked from lived experience, so he remained at all times a humanist, and that underlies his whole career,” Parker says.

In all Davis’s pieces, representational elements — but almost no people — bleed subtly into our recognition from hued planes and black tendrils. The effect is reminiscent of an ordered melodic structure running through the cacophony of a Miles Davis improvisation.

“In Full Swing” delivers one stunning, if safe, masterwork after another. In the process, it excludes pieces from his formative early years and aesthetic sidebars that may not have made for such a neat narrative but were nonetheless instrumental to the artist Davis became. Still, to see textbook works from the mid-1920s to the ’30s in this elegant, intelligent dialogue is a real treat.

“Even in his most abstract works, Davis worked from lived experience,” says Hirschl & Adler’s Tom Parker, “so he remained at all times a humanist, and that underlies his whole career.”

Odol, 1924

Many of his classic pictures exude an American maleness, charming because they are laced with a human warmth rather than misogyny. In Lucky Strike (1921), for example, Davis borrows the layout of the cigarette packaging — its green, red, black, gold and lettering — to construct a geometric architecture evocative of a modern cityscape. There’s no virile spokesman selling stuff we may not need, and even the product name is sidelined to the left and treated more like pure form.

The painting Odol (1924), an image of a popular 1920s deodorant by that name, likewise transforms the product into shapes and text, including the marketing motto: “It Purifies.” A celebration/parody of American consumerism and our obsession with tidy bodies worthy of Andy Warhol, this work was painted — shockingly — four years before Warhol was even born.

Like the musicians who mastered our quintessential American mutt music — fabulous jazz — Stuart Davis scavenged everything around him to create eloquent works with ingenuity and intensity. Yet he also retained a Yankee sense of play and hopefulness that you just don’t see in the works of hard-core European abstractionists, with their search for ultimate purity. Davis preferred the underbelly, the side street, the burlesque bar and a rich and varied landscape. Hands down.