January 8, 2018Taxidermy remains popular among designers, including Ken Fulk, who mounted a giraffe head over the fireplace in his Warren Callister–designed San Francisco home. Photo by Douglas Friedman. Top: This Manhattan apartment by Ryan Korban features a taxidermied grey crowned crane. Photo by Brittany Ambridge

Taxidermy captures animals in an eternal moment of animation, so perhaps it’s fitting that the deployment of these preternaturally preserved creatures as decorative accents has endured far longer than the sell-by-date for most design trends. Certainly, its style-setting enthusiasts are as passionate as they are many.

Martha Stewart is a lifelong lover of the preservationist’s art, and she has proudly posed with the vintage game birds, foxes and bears that adorn Skylands, her 1920s retreat in Seal Harbor, Maine. Angelina Jolie began an avian menagerie when her daughter Shiloh brought home a dead bird she wanted to keep as a pet. Danielle Steel has an elegant Paris residence packed with exotic specimens, including a giraffe in the foyer. A few years ago, Sean Parker hosted a taxidermy party at Davos complete with taxidermied animal heads with laser beams shooting out of their eyes. If that sounds like the climax of this craze, think again. Over-the-top taxidermy remains the flashy signature of party planner and decorator extraordinaire Ken Fulk.

Curiously enough, the latest iteration of this decorative trend had rather modest, if wry, beginnings. Mounted deer heads and antlers started appearing on the walls of hipster pads and boîtes around this century’s turn, when the young and design savvy were blending urban and rustic styles as part of a new back-to-nature movement. Then, in 2003, Brooklyn designer Jason Miller supercharged the movement’s ironic posture with his pricey ceramic-cast Superordinate Antler chandelier, which became a ubiquitous fixture in posh homes. Rather than fading out by decade’s end, the decorative obsession with animal parts was fueled by the debut, in 2007, of the starkly beautiful Stag T stool and benches by the high priest and priestess of fashion forward, Rick Owens and Michele Lamy.

“Most people wouldn’t go for this, but the client thought it was fun,” says Summer Thornton, who added a taxidermied antelope head above the nightstand in this French Tudor–style home in Bloomington, Illinois. “The homeowner isn’t the hunting type, so this feels extra playful.” And it’s guilt-free: “When we do use taxidermy, we always source vintage pieces so that we’re reusing something beautiful and natural without harming any animals.” Photo by Werner Straube/Josh Thornton

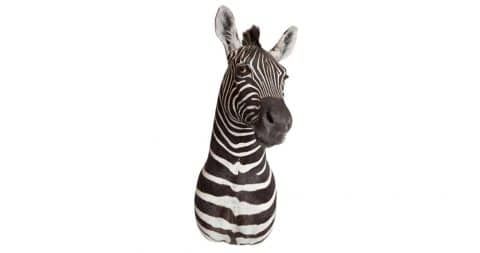

In a Central Park South apartment, Ryan Korban, designed the living room “to feel like a new take on traditional,” he says. “The mixture of various materials with a common thread of black, white and gray became a fresh way of using romantic references. The zebra was created by François Daneck in Paris.” Photo by Brittany Ambridge

For Chicago decorator Summer Thornton, the reason for taxidermy’s persistent appeal is obvious: “There’s nothing more beautiful than natural creation.” New York designer Ryan Korban, agrees: “They add a layer of whimsy to a room that no other decorative arts element can give.” Patrick Mele, another New York designer, thinks there’s a spiritual component to this attraction. These creatures, he says, “are a special gift to be around. Birds, especially, are so colorful they look hyper-real. They remind us those crazy colors are right there in nature.” So passionate is Mele about taxidermy that he’s included a carefully curated collection of specimens in his new eponymous shop in Greenwich, Connecticut, which specializes in the rare and marvelous.

Some observers thought the trend peaked a couple of years ago, when just about every other published interior featured a peacock glamming it up on a pedestal in the corner, tributes perhaps to the albino and jewel-hued pair in Trevor and Alexis Traina’s fabulous San Francisco mansion designed by Thomas Britt and Ann Getty. But Jamie Creel, of Creel and Gow — a Wunderkammer of splendid creatures, exotic objects, textiles and jewelry located on Manhattan’s Upper East Side — says the boutique “still sells a crazy amount” of the alluring birds, along with a constantly changing inventory of other handsome beasties.

The shop recently shipped a stuffed zebra to Palm Beach — “for the season” Creel jokes. In addition, Creel and Gow handles requests from all over the country for custom taxidermy pieces. When we spoke, Creel was busy gathering a bevy of game birds to serve as part of the decor for a Christmas party in Charlottesville, Virginia, artfully arranged to look as if they were running down the dining room table.

A pair of taxidermied peacocks flank the window in the dining room of Trevor and Alexis Traina’s San Francisco home designed by Thomas Britt and Ann Getty. Photo by Simon Upton

“Taxidermy is at once extravagant and naïve, appealing to both our sense of fantasy and our innate fascination with our wild distant cousins on the taxonomic chart.”

In the mid-19th-century home he designed for his parents, Patrick Mele set on the mantel a taxidermy bird sourced from Creel and Gow, his “go-to guys” for taxidermy. Photo by Brittany Ambridge

Such a table adornment wouldn’t have been out of place at Versailles. And that’s part of the timeless charm of the taxidermic tableau. It’s at once extravagant and naïve, appealing to both our sense of fantasy and our innate fascination with our wild distant cousins on the taxonomic chart.

Some of the finest examples of the taxidermist’s art can be viewed at the venerable Parisian shop Deyrolle. I first became acquainted with that storied venue more than 30 years ago, when my Vogue office mate returned from a jaunt to the City of Light with an extraordinary souvenir: a beautifully mounted stag beetle. Jet black, with enormous, menacing mandibles, it was as chic as a bug could be. Which was fitting, as my office mate was none other than Isabella Broughton, later the celebrated style setter under her married name, Blow.

Issie regaled me with descriptions of the extraordinary emporium, with its elaborate displays of fauna ranging from beetles and butterflies, seashells and coral to cheetahs and lions, monkeys and owls, polar bears and peafowl — in short, just about the whole of earthly creation. (Let me hasten to state here that almost all the animals at Deyrolle died of natural causes, with a few culled to curb overpopulation. The specimens at Creel and Gow and Patrick Mele departed similarly.)

Issie was taken with not just the glamour of Deyrolle but also its history. Since its founding, in the 19th century, this national treasure has been on a mission to educate the French about the beauties of the natural world through both its gorgeously preserved and imaginatively displayed specimens and the exquisitely illustrated books, charts and models it produces.

The current owner and steward of this much-cherished enterprise is Prince Louis Albert de Broglie, a committed environmentalist and gardening entrepreneur with a château in the Loire Valley where he sustainably farms 650 varieties of tomatoes. To promote Deyrolle outside France, he has just published a lusciously illustrated book, A Parisian Cabinet of Curiosities: Deyrolle (Flammarion).

In his London townhouse, Hubert Zandberg created a Wunderkammer to house his personal collection of taxidermy, curiosities, objets trouvés and contemporary art, combining these with design furniture and industrial salvage pieces. Among his treasures is a rare pair of original deer-antler walking-stick stands, 1900–20, displayed atop glass cases. Photo by Simon Upton

“The antler trophies, which I purchased at auction, reflect what traditionally would have been found in the entry hall of a French country house,” Timothy Corrigan writes in his book An Invitation to Château du Grand-Lucé, about his home in France. Photo by Eric Piasecki

An appreciation of the natural world has inspired many great artists. Some of the best Flemish and Dutch Old Masters focused their talents on depicting then-exotic birds and animals, retrieved from faraway lands by explorers, in highly dramatic, utterly unlikely compositions. For the past four years, the Dutch collaborative Darwin, Sinke & van Tongeren has been creating taxidermy compositions that riff on those Old Masters’ works, attracting a devoted following among natural history enthusiasts, art collectors, museum curators and interior designers. Perhaps the most famous and notable of these is Damien Hirst, who, at the collaborative’s second gallery show in London, in 2015, bought up nearly every piece for his personal collection, Murderme.

Typical of the enterprise’s prankish spirit, this threesome is actually a pair, Ferry van Tongeren and Jaap Sinke, who up until six years ago worked together in van Tongeren’s ad agency, Doom & Dickson. They gave a nod to Charles Darwin in their name because their work is dedicated to showing the beauty and magic of nature.

In addition to their Old Master–inspired compositions, the two also photograph the skins and pelts of creatures in the soapy basins used to wash them. Van Tongeren got the idea when, as an apprentice, he was struck by the image of a collapsed ostrich in a huge concrete tub. “The bird faded out in the milk-colored water like an aquarelle,” he recalls. For their series “Unknown Poses,” the duo positioned the animals in ways that would be impossible in life, a feat that “took a lot of practicing,” says Van Tongeren, but the images are as captivating as they are original.

Irony abounds in this new decorative obsession. When taxidermy’s techniques were perfected, in the 18th century, it was largely to assist amateur naturalists in their study of birds. Yet this was also the century that marked the dawn of the Industrial Age, which many scientists today claim is when the earth entered the Anthropocene Era, a geological period distinguished by humanity’s significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems, including species extinction. Today, even as we continue to delight in living — and decorating — with beautifully preserved wild creatures, their living counterparts are vanishing forever from the earth. And there is nothing glamorous about that.