July 3, 2022The Oxford Dictionary defines provenance as “a record of ownership of a work of art or an antique, used as a guide to authenticity or quality.”

Provenance can enhance value: Being associated with a nobleman, connoisseur or noted collector adds to the status of a painting or work of art or antique or vintage couture.

Then there is provenance as pedigree. In the early 1900s, Duveen Brothers marketed British portraits belonging to the British aristocracy to Americans Henry Clay Frick, J.P. Morgan and Henry Edwards Huntington.

“The association of a painting with an aristocratic name or, better yet, a princely one was particularly important when selling a portrait,” Elizabeth A. Pergam writes in Provenance: An Alternate History of Art, a 2012 Getty Research Institute book edited by Gail Feigenbaum and Inge Reist.

“In using the vocabulary of breeding, dealers reinforced the idea that the quality of a painting could be judged by the prestige of the family who had owned it,” Pergam writes. “Both Duveen Brothers and M. Knoedler & Co. explicitly called a painting’s provenance and its exhibition history the work’s ‘pedigree.’ ”

The power of provenance is as strong today.

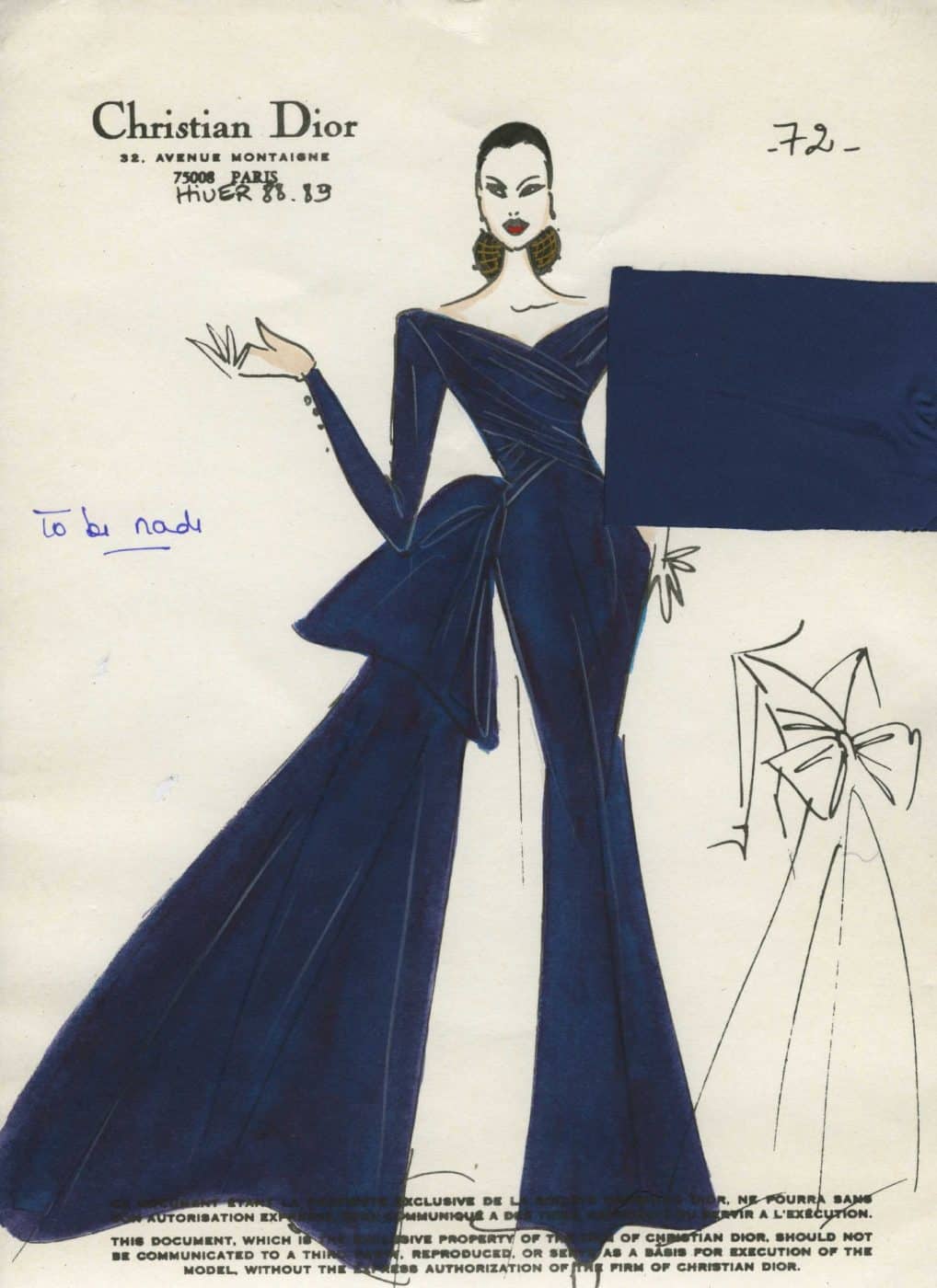

Betsy Bloomingdale’s Christian Dior Gown

“Provenance is the exclamation point when you are making a sale,” says Elizabeth Mason, the owner of The Paper Bag Princess Vintage Couture, in Beverly Hills. “It doesn’t have to be a celebrity. To the right person, provenance is important. My pieces come mostly from clients who had incredible lives, like Betsy Bloomingdale and Leonore Annenberg. So, I like to share the history of pieces and their former owners.”

Bloomingdale was known for her haute couture wardrobe — she was a regular on the international best dressed list — and generous hospitality extended to friends like Nancy Reagan, Joan Collins, Nan Kempner and Lauren Bacall. Mason’s relationship with the Bloomingdale family is both close and enduring — today Bloomingdale’s grandson’s wife is a client.

“I made several visits to Betsy’s couture closet over the years — every gown had a tag listing when she wore it, the name of the event and who attended the party,” Mason recalls. “I got a large collection of gowns from her.”

One of them is now for sale: a long, blue silk-taffeta gown from the Christian Dior Haute Couture Collection of 1988–89.

Originally from Toronto, Mason is a certified appraiser and has her own archival design research department, with a library of fashion books and sketches. Her list of customers includes Julia Roberts, Catherine Zeta Jones, Donatella Versace and Kourtney Kardashian.

She is candid about how she determines an item’s price.

“I ask myself: ‘To whom did it belong, and who designed it? Does it transcend fashion? Is it a collector piece? What is the condition? Rarity? Aesthetic? Is there anything similar for sale? What will the market bear?’ ”

Grand Ducal Tables from Stoneleigh Abbey

Bill Rau, the third-generation owner of M.S. Rau, in New Orleans, is an expert on provenance. He takes out a daily ad in the Wall Street Journal that focuses on one single antique, its history and appeal, often including a stellar lineage.

He is currently selling a pair of large pietre dure consoles with a “triple provenance.” The top surfaces are covered with rectangular panels depicting birds and flowers in intricate detail using rare decorative hard stones, such as lapis lazuli and pietra paesina. They are attributed to Florence’s grand ducal workshops of the first half of the 17th century. Established in 1588 by the famous art patron Grand Duke Ferdinando I de Medici, these ateliers were known for the high level of their craftsmanship, attracting a clientele that included popes and European royalty.

The baroque table bases are equally illustrious in origin. They were carved around 1714 by the renowned Venetian wood sculptor Andrea Brustolon, dubbed the “Michelangelo of wood.” (His work is in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Ca’ Rezzonico in Venice.) Here Brustolon has carved cupids, masks and foliage in three dimensions to great effect.

The tables’ pedigree is also great.

Former owners include Lord Leigh, whose family held the country estate Stoneleigh Abbey (now a National Trust house), near Coventry, from 1561 to 1990. He sold the tables at Christie’s in 1962 to a family in Florence that, a half century later, sold them to Rau.

Asked about the importance of provenance, Rau replies, “It depends on the piece. Provenance is used for two things. It can authenticate something, or it can add value. Sometimes who owns a piece is more important than anything.”

“In the early nineteen sixties,” he continues by way of example, “[President John F. Kennedy] bought twelve plain rocking chairs because they supported his bad back. They were nothing special. If you saw a similar one in a consignment shop, you might spend thirty dollars for it. Now, when the JFK rocking chairs come up for auction, they go for between four hundred thousand dollars and six hundred thousand dollars apiece.”

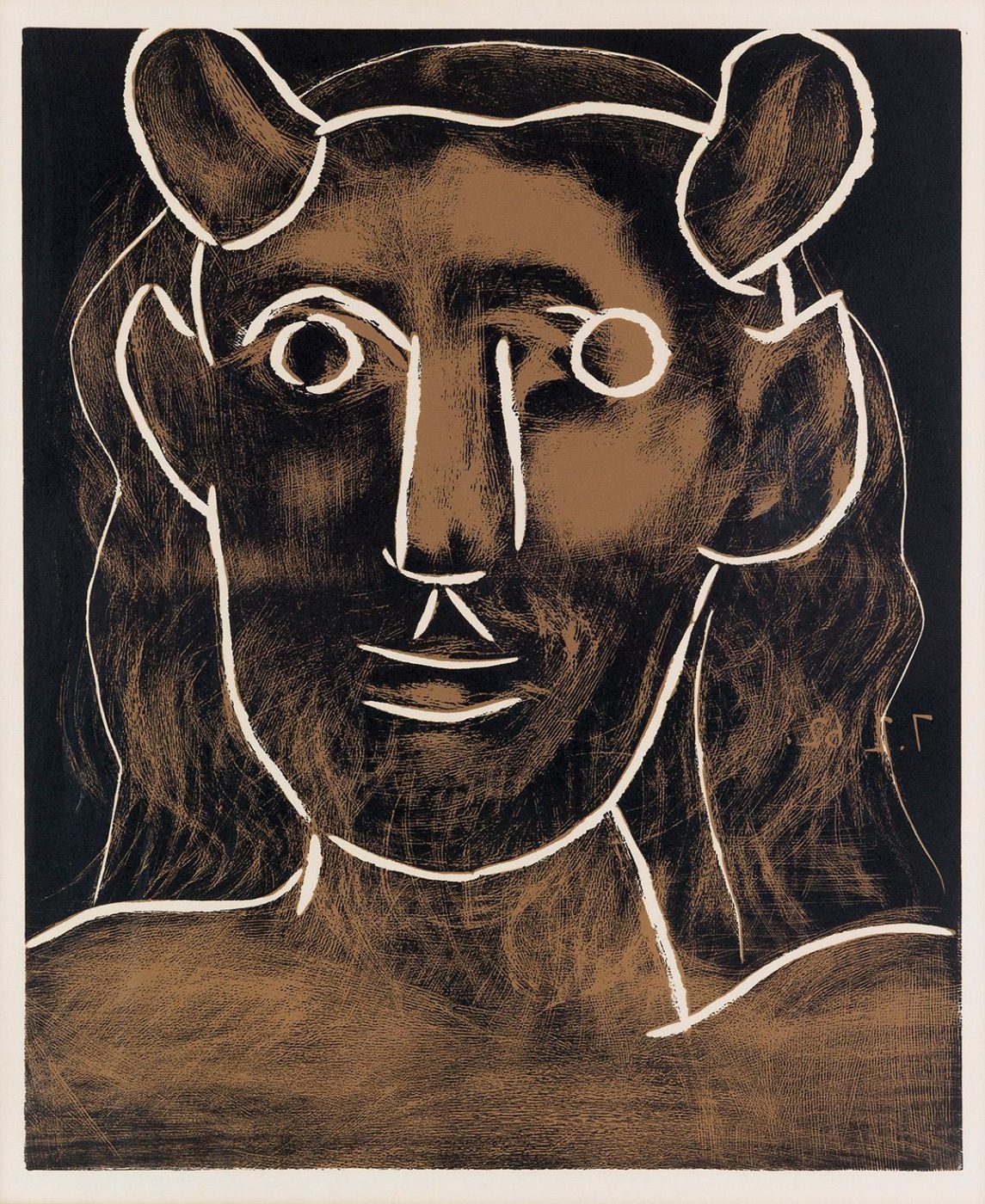

A Picasso Print from the Artist’s Granddaughter

Provenance is important in fine art as well.

Kristina Weyman and her brother-in-law Ross Weyman are codirectors of the Chicago- and New Jersey–based gallery DaMats Fine Art Collaborative, which opened in 2020.

They are currently offering a 1962 linocut printed by the late Hidalgo Arnéra, of Vallauris, France, of a Picasso Tête de faune. It is an unsigned, unnumbered proof (there are 50 numbered impressions), but it has an important past.

The print was inherited by Marina Picasso, Picasso’s granddaughter, and bears her ink collection stamp on the reverse side. After she sold it to someone else — she loathed her grandfather — DaMats bought it.

“Provenance is very important in terms of authentication,” Kristina Weyman says. “A strong provenance directly affects an item’s value.”

Dodie Rosenkrans’ Mughal Sword

Joseph Saidian and Sons, fourth-generation estate jewelers in Manhattan, have a 19th-century bejeweled Mughal sword that once belonged to Dodie Rosenkrans. A beloved San Francisco philanthropist, international society hostess and haute couture devotée, who died in 2010, Rosenkrans was known for her patronage of the arts and her large, extravagant jewels.

Her sword, called a shamshir because it has a curved Persian-style blade, is 39 inches long. The horse-head-shaped gold hilt is elaborately set with emeralds, rubies and diamonds. The blade is inlaid with gold calligraphy that the gallery surmises is a kind of religious blessing. The weapon is so spectacular it may have been commissioned as a gift or as regalia for a special ceremony.

The Saidians bought it from a middleman who purchased the Rosenkrans jewelry collection from her estate.

“We don’t know how or where she got this gold Mughal sword, but it’s a rarity to have something like this come out of India,” says Ariel Saidian, noting that families don’t tend to part with special pieces like this one.

It is also unusual that the sword-and-sheath set has never been broken up. “Normally, a piece like this would end up in an institution or a museum,” says Saidian. “But I think it will go to a private collector, a man who will mount it on the wall of his home office.”

Bunny Mellon‘s Bracelet

With a provenance like Bunny Mellon, even a piece of costume jewelry can command a solid-gold price. Mellon stands for old money, classic chic — pedigree, in other words.

Mark Walsh and Leslie Chin — partners in Vintage Luxury, a fashion, accessories and jewelry dealer in Riverdale, New York — have a Mellon costume bracelet that looks like the real thing.

It is a 1950 bangle made of gold-washed sterling silver studded all over with faux diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds.

“Bunny Mellon was not glamorous, but she had fine clothes. In fact, a lot of them are in museums now,” says Walsh. “She became good friends with Givenchy and Balenciaga.

“When she was photographed, she wore real jewelry,” he continues. “But she had mounds of costume jewelry. Bunny Mellon shopped to the point where she bought anything that grabbed her attention. It was insane.”

Walsh has sold other of her pieces to customers whom he describes as “really cool, chic people.”

Mellon bought this bracelet from Jolie Gabor, a Hungarian-born American jeweler who was the mother of the glamorous Hollywood sister/actresses Magda, Zsa Zsa and Eva.

Jolie — who owned five jewelry shops in Budapest before coming to America, in 1945, and marrying Count Odon de Szigethy — had a shop at 699 Madison Avenue.

Glamorous and social, she was a regular at the popular Manhattan nightclub El Morocco and, in 1975, coauthored her memoir with prominent gossip columnist Cindy Adams. Jolie died at age 100 in Palm Springs, where she had another shop.

Asked if illustrious provenance made for higher prices, Walsh says, “It helps a little but doesn’t help the intrinsic value of a piece that much. It’s not like quadrupling the price.”

After a pause, he continues, “Of course, if we found a picture of Bunny wearing the bracelet, it would be more.”

Shirley Temple Black’s Settee

Automaton, a vintage furniture store in Culver City, California, has a fine piece of 1950s outdoor furniture with a true sentimental celebrity provenance: the settee belonged to Shirley Temple Black, America’s sweetheart.

As a child, Shirley Temple was Hollywood’s number-one box-office draw from 1934 to 1938, acting, singing and dancing in scores of movies. As an adult, she served as U.S. ambassador to the U.N., Ghana and the Czech Republic, dying at the age of 85 in 2014.

Dexter Hutchison, the owner of Automaton, purchased the settee from

Black’s estate and meticulously restored it. It was designed by the California architect Walter Lamb for Brown Jordan in about 1955, with a tubular copper frame and nylon cording for support. Hutchison calls it an “example of functional mid-century modern art.” Lamb’s patio furniture designs for Brown Jordan are still popular and continue to be made — but not this settee.

As for its provenance, Hutchison adds: “If you happen to love Shirley Temple and you were in the market for Walter Lamb furniture, which would you choose if two options of the same piece were offered at the same price? Maybe you would even pay a little more for the one owned by her if that provenance can be confirmed. It’s an incredibly rare example from the early years of Lamb’s work with Brown Jordan,” Hutchison says. “It’s sexy and curvy.”