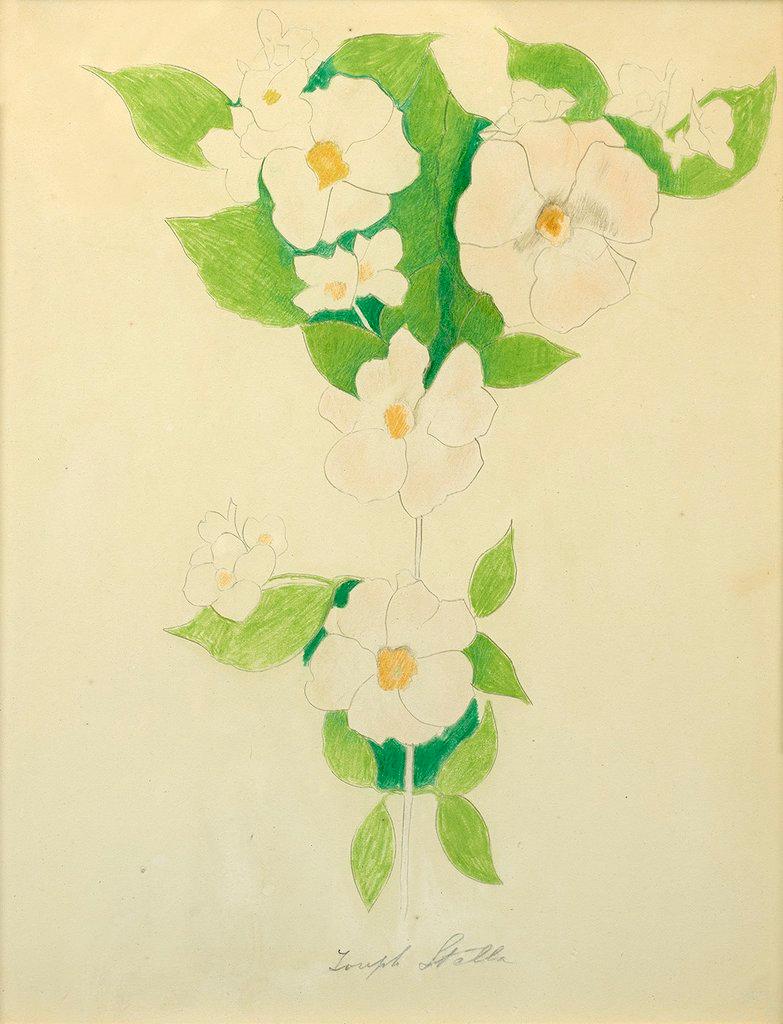

Silverpoint and colored pencil on paper, 29 x 23 in.

Signed (at lower right): Joseph Stella

Executed about 1919

EXHIBITED: Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, November 23, 1985–January 4, 1986, American Masterworks on Paper: Drawings, Watercolors, and Prints, pp. 6, 46 no. 47 illus. // (probably) Richard York Gallery, New York, October 5–November 17, 1990, Joseph Stella: 100 Works on Paper, no. 36

EX COLL.: [Dudensing Galleries, New York]; sale, Christie’s, New York, December 7, 1984, lot 324; [Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, 1984]; to private collection, 2006 until the present

An independent-minded artist who adhered to the credo “Rules don’t exist,” Joseph Stella explored a range of styles, media, and themes, willfully ignoring the “barricades erected by ... [the] self-appointed dictators” of the art establishment (Joseph Stella, “On Painting,” Broom 11 [December 1921], pp. 122–23; Joseph Stella, “Discovery of America: Autobiographical Notes,” Art News 59

[November 1960], p. 41). By doing so, he produced a diverse and highly eclectic body of work, ranging from realist figure subjects, pulsating Futurist cityscapes, and modernist religious images to poetic portrayals of natural forms and sensuous tropical landscapes. However, whatever his subject or mode of expression, Stella infused his paintings and drawings with two consistent elements: a masterful handling of line and a visionary quality that was uniquely his own.

Born in Muro Lucano, a hill town near Naples, Italy, Stella was a son of Vincenza Cerone Stella, a prominent lawyer, and his wife, Michele. As a young boy, he developed an interest in drawing, acquiring––in keeping with his country’s rich artistic past––a strong appreciation for the work of the Old Masters, particularly the artists of the Italian Renaissance. In 1896, after completing his classical education in Naples, Stella moved to New York, where his older brother, Antonio, had established a successful medical practice and was a respected member of the Italian-American community. At the urging of his sibling, Stella began studying medicine. However, in the late fall of 1897 he abandoned this endeavor and studied simultaneously at the College of Pharmacy of the City of New York and at the Art Students League of New York. As it turned out, Stella’s affiliation with both institutions was brief. In 1898, determined to pursue an artistic career, he enrolled at the New York School of Art (known today as Parsons, the New School for Design), where, over the course of three years, he refined his skills as a draftsman under the tutelage of William Merritt Chase, who shared his admiration for Old Master painting. Under Chase’s guidance, Stella developed a passion for line that remained with him for the rest of his career. Stella would eventually emerge as one of the finest draftsmen of his generation, known for his painstaking technique.

During his early years in New York, Stella supported himself by working as an illustrator for leftist publications, such as The Outlook and Everybody’s Magazine, making detailed and highly sensitive drawings of workers, factories, and European immigrants newly arrived in New York. In his spare time, he painted urban subjects, emulating the down-to-earth realism of Ashcan School painters such as Robert Henri. A turning point in his career occurred in 1909, when Stella went back to Europe, dividing his time between Italy and France. While in Paris, he roamed the galleries, viewing examples of Fauvism, Orphic Cubism, Symbolism, and Italian Futurism that subsequently provoked his new concern for vanguard precepts of form and color.

Returning to New York towards the end of 1912, Stella exhibited a fauvist-inspired still life at the groundbreaking Armory Show (International Exhibition of Modern Art) and joined the circle of progressive-minded artists, such as John Marin and Max Weber, who gathered at the West Side apartment of the art patron Conrad Arensberg. He also befriended the influential dealer and photographer, Alfred Stieglitz, and the pioneering Dadaist Marcel Duchamp. Responding to the energy, chaos, and “dazzling array of lights” he encountered in the urban environment, Stella went on to paint his Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras (1913–14; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut), a swirling semi-abstract composition in which he conjoined the fragmented forms of Cubism and Futurism with a prismatic palette (“I Knew Him When,” Daily Mirror [New York], July 8, 1924). It was, he said, his “first truly great picture,” and it continues to be viewed as an icon of American modernist painting (ibid.). In the ensuing years, Stella continued to work in a progressive style, applying the precepts of Modernism to images of Manhattan’s lights and landmarks, particularly the Brooklyn Bridge, which, as Barbara Haskell has pointed out, he “elevated ... into a spiritual symbol at once majestic and monstrous” (Barbara Haskell, Joseph Stella, exhib. cat. [New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994], p. 85). However, in keeping with his non-conformist outlook and his refusal to affiliate himself with any single movement, Stella took his art in entirely different directions as well. Indeed, around 1919, seeking to create a blissful environment filled with tranquility and innocence, Stella

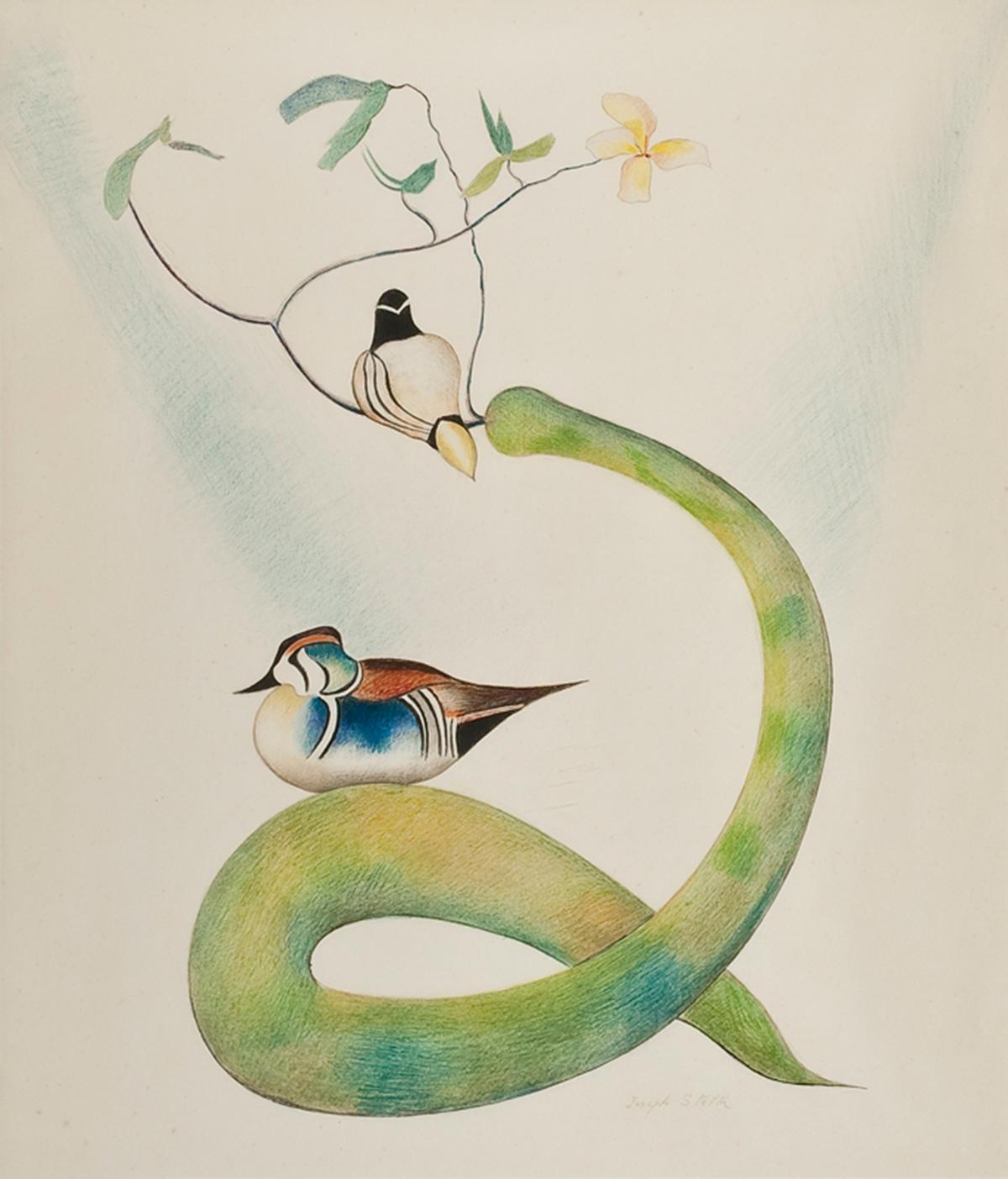

turned his attention to intimate drawings of flowers, birds, and butterflies conceived as spare, minimalist shapes isolated against an unadorned background in a manner not unlike that found in Asian art. (Flowers were particularly important to Stella, who once said: “My devout wish, that my every working day might begin and end––as a good omen––with the light, gay painting of a flower” (Joseph Stella, “Thoughts, II,” undated manuscript, quoted in Haskell, p. 220). Rendered in silverpoint and colored wax pencil with an amazing degree of precision, these personal excursions into representational realism exude a contemplative tone, their gentle lyricism acting as a foil to Stella’s frenetic, motion-filled cityscapes and mechanistic industrial scenes. (Along with artists such

as Thomas Wilmer Dewing and Philip Leslie Hale, Stella was among the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century American painters to embrace the art of silverpoint, a demanding technique, first used by ancient scribes and artists and later Old Masters, which involved drawing with a fine-tipped silver rod on a surface often primed with a light coating of gesso. Drawn to the thin, pure line created by silverpoint, as well as by the medium’s inherent light-reflecting quality, Stella once described the meticulous process of cutting “with the sharpness of my silverpoint” as a “sensuous thrill.” (See Joseph Stella, “Autobiographical Notes,” Joseph Stella Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., reel 346, frames 1260–76. See also, Haskell, pp. 120–27.)

Stella’s depictions of the natural world include Lily and Bird, which features a sparrow resting on a meandering tendril in the lower

register of the composition. A Madonna Lily––its stem as straight as a ramrod––occupies the center of the design. (The composition is almost identical to that of Lilies and Sparrow [about 1920], in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. See Jane Glaubinger, “Two Drawings by Joseph Stella,” Bulletin of The Cleveland Museum of Art 70 [December 1983], pp. [392]–94; and Haskell, p. 113.) Both the bird and the lily held symbolic significance that Stella was surely aware of, the former serving as a visual metaphor of freedom (one thinks of Stella’s own desire for aesthetic independence) and the latter interpreted as an emblem of purity, devotion, and rebirth. A second, smaller blossom, which hovers in space behind the sparrow, adds an enigmatic, otherworldly quality to the vignette, reminding us that Stella’s drawings of flora were magical––a world apart from traditional botanical illustration and Victorian flower painting. The ethereal quality that permeates the image is further enhanced by the limited palette of soft greens, golds, browns, and subtle greys, attesting to the fact that Stella was just as comfortable using a restrained color scheme as he was with bold, vivid hues.

In 1920, Stella had his first retrospective exhibition, held at The Newark Museum in New Jersey. During that same year, he was appointed to the exhibition committee of Katherine Dreier’s Société Anonyme, along with Duchamp and Man Ray. He also published his first lecture on art in Broom, a magazine devoted to contemporary art and literature, and in 1923, he became an American citizen. However, Stella’s emotional ties to the Old World remained strong. In 1926, he deposited his work with the Dudensing Galleries (his dealer from 1925 to 1935) and set sail for Europe, where, for the next eight years, he divided his time between Paris and Italy while making the occasional trip back to America for exhibition purposes. Inspired by visits to locales such as Siena and Assisi, he painted a series of dramatic Madonna pictures, combining the strategies of Modernism with a distinctly

Italian spirit, as in The Creche (The Holy Manger) (about 1929–33; The Newark Museum, New Jersey). Stella’s work from this period also includes fantastical paintings with highly simplified forms that reflect the impact of Surrealism, as in his Tree, Cactus, Moon (1927–28; Reynolda House, Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina) and Lotus (1929; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.)

Upon returning to New York in the autumn of 1934, Stella found himself at the fringe of the art world, having lost touch with many of his former friends and associates. Moreover, his latest work, theatrical and reflective of his Italian roots, was generally ignored, eclipsed by the new taste for Regionalist painting and by the advent of Abstract Expressionism. To make ends meet, he painted

oils for the easel division of the Works Progress Administration and began experimenting with collage. A trip to Barbados with his ailing wife in 1937 resulted in brightly colored portrayals of the tropics.

In 1940, Stella was diagnosed with heart disease. Three years later his condition, coupled with newly developed thrombosis in the eye, led to frequent periods of confinement in his bed. Nevertheless, Stella continued to work, producing drawings of flowers and fruit until the spring of 1945, when a fall down an elevator shaft curtailed his artistic activity altogether. Stella subsequently died of heart failure on November 5, 1946. For many years, his position in the annals of American art rested on his pre-1923 work, especially in relation to his role as a pioneer of American modernist painting. However, this oversight was rectified in 1994, when the Whitney Museum of American Art organized Joseph Stella, a major survey exhibition which emphasized the broad diversity of his creative activity and his multicultural point of view. As observed by Holland Cotter, the show represented the work of a “maverick” artist who embraced an “internationalist sensibility whose sources stretch far beyond the confines of modernism” (Holland Cotter, “Painterly Synthesis of a Wanderer’s Life,” New York Times, April 22, 1994).