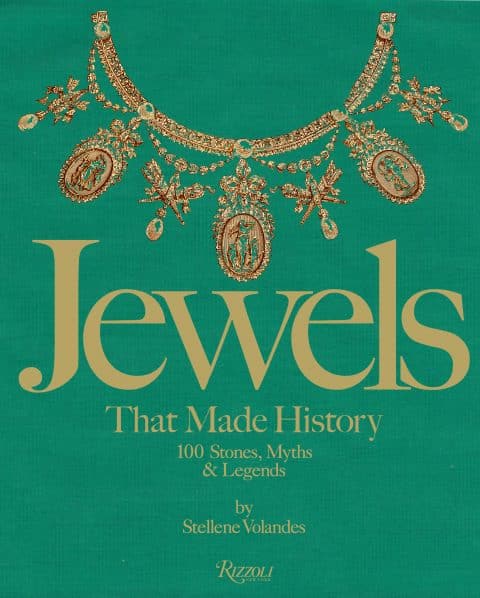

October 18, 2020Stellene Volandes’s new book, Jewels That Made History: 100 Stones, Myths and Legends (Rizzoli), opens with a caveat and a mission statement: “This is not the history of jewelry. And it is not a history of the world,” Volandes explains. “Rather, this book is a highly opinionated chronicle of select moments where these forces collide.”

Highly opinionated — about jewelry, about fashion, about design, about Broadway, about where you should have dinner tonight and what you should order — is an accurate way to describe Volandes. It’s also an important part of what makes her good at her job — or rather, jobs: The editor in chief of Town & Country magazine since 2016, she is, in addition, the editorial director of Elle Decor. (Asad Syrkett, formly of Curbed, Architectural Digest and Architectural Record, was named the shelter pub’s editor in chief, reporting to Volandes, last month.)

Her strong opinions also make her a hoot to talk to about, well, pretty much anything. That’s something I started to appreciate more than a decade ago, when we became colleagues at Departures magazine, and it’s what I continue to love about her all these years later as a dear friend. She tells it like it is, or at least as she sees it, and with punchlines and surprises to spare.

In Jewels — her second book with Rizzoli, following the 21st-century-focused Jeweler: Masters, Mavericks, and Visionaries of Modern Design — Volandes acts as the Virgil to our Dante, guiding us along a timeline of world history made up of jewelry’s greatest moments. As guides go, she’s a bit of a gossip, but then the best ones usually are (sorry, Virgil).

From a lapis lazuli, turquoise and carnelian pectoral dating to 1292 BC, uncovered in King Tut’s tomb, to the Tiffany & Co. diamond Lady Gaga wore at the Academy Awards last February, Volandes takes us on a fast-paced, globe-hopping romp to reveal what she describes in the book’s pages as “the treasures of history and myth that jewelry can hold for us all.”

Volandes knows these jewels and their history cold, but what’s even more compelling about the book is her love for her subject. That’s apparent on every lushly illustrated page, and it makes these vignettes of conquest and hardship, dynasty and destruction utterly fascinating — even for those who think they don’t give a fig about fine jewelry.

Here, Volandes shares with Introspective more opinions about some of the world’s most famous jewels and the historic moments to which they bore witness.

Your first book had a contemporary slant. This one takes a long look back. Why did you want to delve into history here? You’re Greek, so the classics are in your blood, of course.

The idea for this book is actually in the first one. In the chapter about Brooklyn-based jeweler Mark Davis, when I talk about Bakelite and the history of plastic, I say I’ve always wanted to create a jewelry timeline of the world — to map out how I see jewelry fitting into history.

Many years ago, I saw these weird Cartier brooches at a jewelry gallery. The dealer explained that they were called Sputnik brooches and were created during the mid-20th-century Space Race, which influenced a whole generation of jewelers. I realized that narratives of history, trade and human desire mark themselves on pieces of jewelry.

This book is about inviting people to see jewelry the way I do. Yes, it’s beautiful. Yes, it’s precious. But it also has the potential to tell the story of conflict, of cultures clashing and of civilization itself.

You use jewelry to draw connections across time and geography. What’s a favorite example of that in the book?

One thing about jewelry is that it’s easily transported. That makes it easy to lose, which is why jewelry history is often more legend than fact. But the fact that it can be transported also means that it often survives.

The Vladimir Tiara has one of the great escape stories of all time: It appears throughout imperial Russian history and then becomes one of Queen Elizabeth II’s favorite tiaras. It made it out of Russia alive, but the Romanovs, for the most part, did not.

To me, jewelry is timeless because the materials are millions of years old. The past is always present.

What three pieces in the book would you add to your personal collection?

I’d love something from ancient Egypt. The Egyptians believed in jewelry as talisman. When I put on a piece, I think about how it’ll make me feel at different points in the day. And gold, carnelian, turquoise and lapis lazuli are my dream palette.

Then, something from Priam’s Treasure, for obvious Greek reasons. When uncovered in 1873, in what’s now Turkey, these were identified as a royal cache dating to the Trojan War. Whether the copper shields and gold diadems and rings were really King Priam’s or not, the thing about Troy is that the legend of it is so powerful, the human instincts related to it are so real, it doesn’t matter. The fact that this treasure trove was discovered deep in the earth after so many centuries, that has value. And Helen’s diadem? I mean!

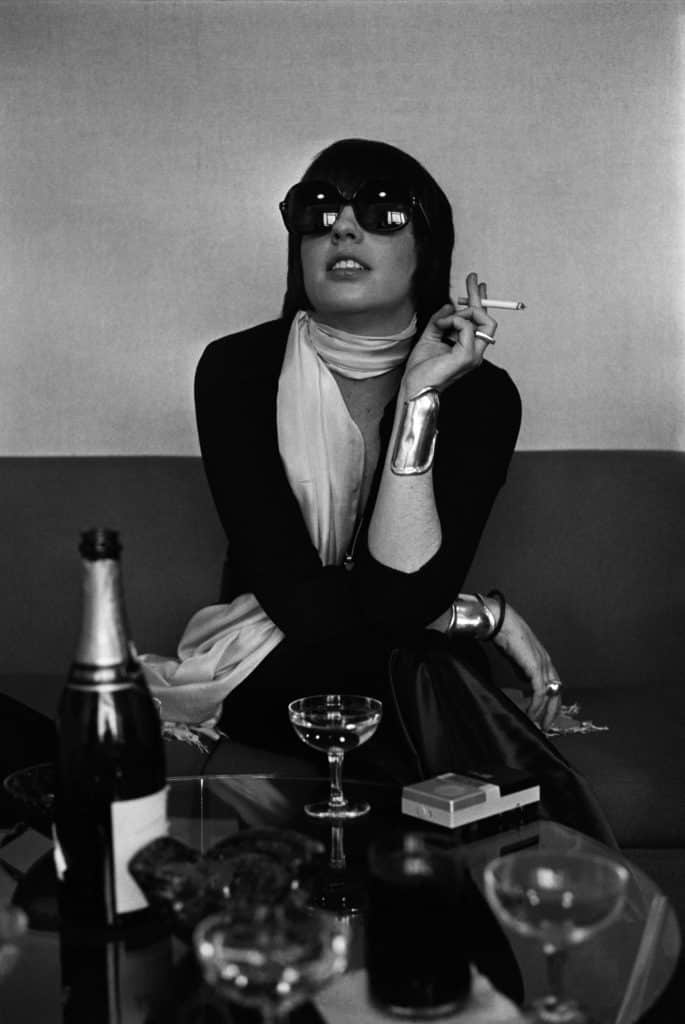

And, listen, I’d love a pair of Verdura Maltese cuffs. I have a Maltese cross that I bought for myself when I became editor of T&C.

As the book heads toward contemporary times, the jewels get a bit more accessible. What are some of the modern, prêt-à-porter pieces that anyone can — and perhaps everyone should — have in their collection?

Jewelry used to just be for aristocrats with private jewelers. At the end of the nineteenth century, with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the middle class, brands emerged. There’s a shift, and that led to the creation of iconic pieces available today: an Elsa Peretti bone cuff, say, or those Verdura cuffs, or something from Van Cleef & Arpels’s Alhambra, Bulgari’s Serpenti or David Yurman’s cable collection. I hope that the book shows why these definitive examples of twentieth-century jewelry design emerged when they did. Even though they are more accessible, they are still artifacts of their time.

As editorial director of Elle Decor, do you see any connections between interior design and jewelry?

It’s interesting to me that we talk about jewelry houses not jewelry companies. Why? Because jewelry is a decorative art, like any other great tradition. When you talk to jewelers, they talk about proportion, placement of each stone. Jewelry has to be worn, it has to be engineered on the body. So form and function, which are at the heart of great design, are also at the heart of great jewelry.

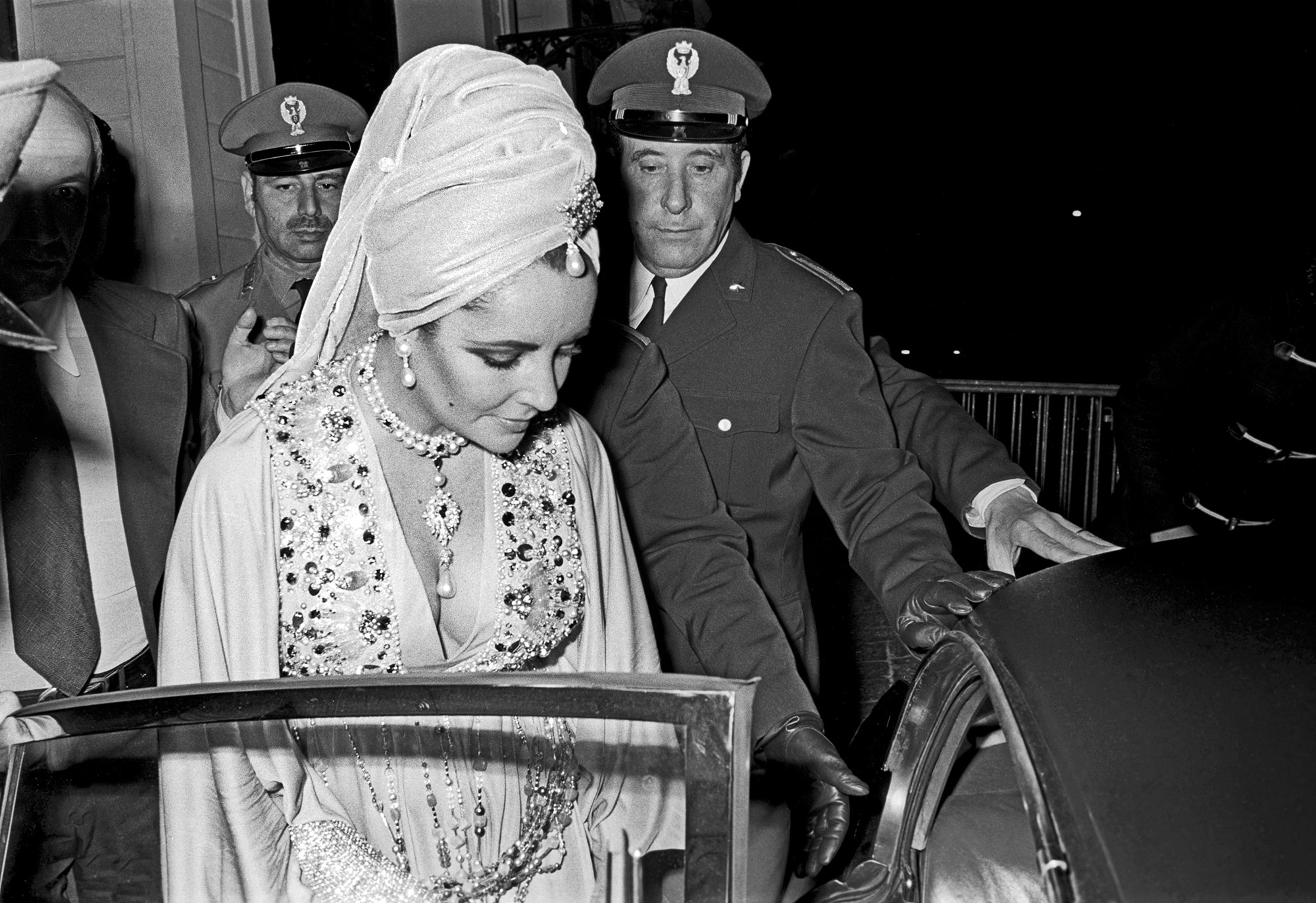

Of the prominent women who appear in your book — Queen Victoria, Coco Chanel, Wallis Simpson, Elizabeths I, II and Taylor — whose taste do you most admire?

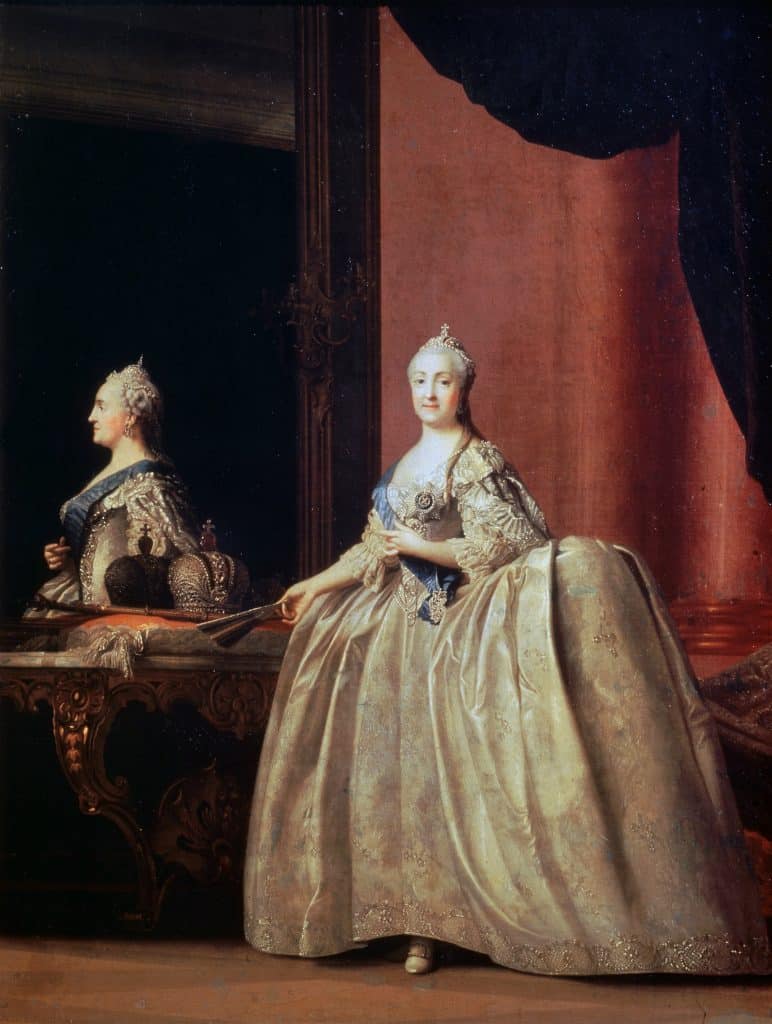

Catherine the Great. I think that, first of all, she loved jewelry, but she loved it because it made her feel powerful. For her, it wasn’t about feeling pretty — it was about staking a claim to power.

The story that really hooked me on her is that when she had a meeting with her generals, who were always really hard on her and never trusted her, she would pile on the jewelry because if she walked into a meeting wearing more emeralds, they’d be more intimidated.

Whether that’s jewelry myth or legend, who knows? But I think about that when I get dressed in the morning, even if it’s just for Zoom meetings.

Speaking of Zoom, is there a moment in the book that speaks to our own time, this period of pandemic, economic turmoil and a moral reckoning about racial and social justice?

I think a lot about Art Deco when we talk about what will happen after this — or because of this. One of the boldest and most courageous periods of jewelry design, it came out of one of the darkest periods of world history. The classics are strong now and selling well. But I think that the 2020s will be very much like the 1920s: We’ll see a feeling of freedom and celebration that we’re all going to want to enjoy, a sense of “Let’s try something new.” That was very much at the heart of Art Deco, when designers threw away the romanticism of the Belle Époque and played with materials no one dreamed of using before. Because they said, “You know what — why not?”

I hope that jewelers will have had time during this period to draw on inspiration and be creative without the pressures they would normally have. I can’t wait to see what they’ll do.