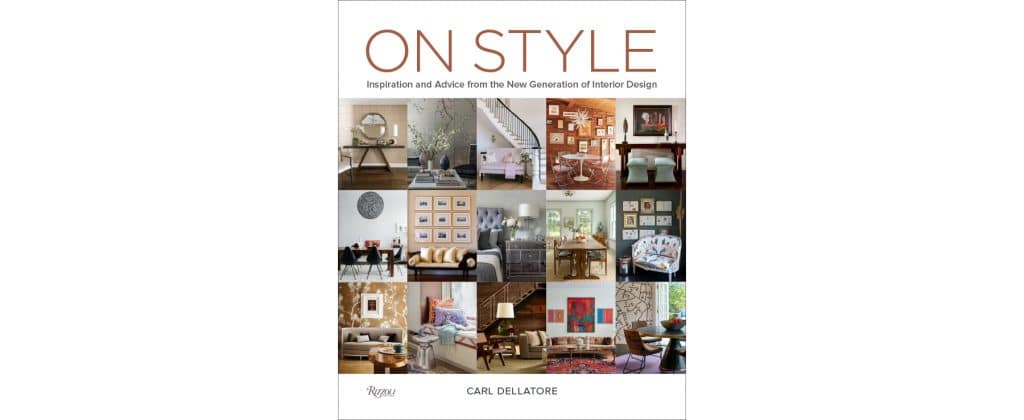

October 20, 2019The new book On Style (Rizzoli), by Carl Dellatore, looks at the work of 50 contemporary interior designers. Among them is Patrick Mele, who designed the family room above, in New York’s Westchester County, around antique Persian carpets his clients bought in Istanbul (photo by Kyle Knodell). Top: Wesley Moon, also featured in the volume, created an alpine fantasy in a New Jersey living room; on the console are Matthew Solomon ceramic tulips from Maison Gerard and a bronze lamp from Valerie Goodman Gallery (photo by William Waldron).

Writing in the New York Times this fall, critic Vanessa Friedman observed that “the gravitational forces of New York fashion are moving; its map is being rewritten and identity reinvented by a group of designers with a different sense of history and voices that demand to be heard.”

And what of interior design? Is it — like fashion — being reinvented by a new wave of designers? The place to find out may be Carl Dellatore’s new book, On Style (Rizzoli), a report on 50 designers who, he writes, not only have great taste but are “moving the discipline forward.” As he notes in the introduction, “Interior design has always been defined by its moment in time, generational movements that are, in turn, shaped by culture, economics, and fashion.”

Of this kitchen, designed by Kevin Dumais, Dellatore writes, “The extra-large island is balanced with an original half-barrel pendant covered in linen, which provides a soft ambient glow.” Photo by Joshua McHugh

In putting together the book, Dellatore found that “design has become democratized. It’s no longer only for the über-rich,” he tells Introspective, adding that “there’s a real proliferation of aesthetic diversity afoot.” The Internet has exposed designers and their clients to more visual information than ever before. As a result, he writes in On Style, “the variety of aesthetic lenses through which designers see interiors is expanding exponentially.”

Left: Kati Curtis found the Art Deco James Mont sofa she used in an apartment on New York’s Upper West Side through dealer Todd Merrill. Right: A chinoiserie wallpaper, hand painted in China, adorns the walls of the apartment’s bedroom. Photos by Brittany Ambridge/OTTO

That may actually make their job more difficult: To prove their worth to clients, designers need to tamp down the visual cacophony while also making sure the rooms they create don’t look like anybody else’s. This generation succeeds in doing just that, with the support of clients who don’t feel the need for furniture that matches or collections of artworks belonging to a single period or genre.

Sean Matijevich, formerly of David Kleinberg Design Associates, selected “a neutral palette punctuated by dark-navy accents” for this living room, Dellatore writes. That spare color scheme “allows the artwork to be the star in this expansive living room, which features works by Andy Warhol and Donald Judd.” Photo courtesy David Kleinberg Design Associates

“With the inundation of inspiration images from Pinterest and Instagram, I think it’s important to find inspiration in singular things,” New York designer Michelle R. Smith tells Dellatore. Smith belongs to the coterie the author calls the Casual Bohemians, who, he says, “mix humble furnishings in exciting ways.”

An artwork by Christopher Wool holds pride of place in the living room of a New York apartment Neal Beckstedt designed for a couple whom Dellatore describes as having “individual design visions.” To meet their differing needs, Beckstedt gave them each their own sofa: a bright teal tufted one for her, a nubby linen one for him. Photo © Eric Piasecki/OTTO

Mixing furnishings — humble or not — makes it possible to satisfy more than one person at a time. Case in point: the Manhattan living room that New York–based Neal Beckstedt — whom Dellatore lists among this Devotees of Masculine Chic — designed with two sofas: one in beige linen for the husband and the other in teal velvet for the wife. The sofas don’t match; they’re fine just coexisting. Beckstedt, who grew up on a farm in Ohio, also knows how to bring rural charm to sophisticated surroundings. In the same apartment, he covered walls in reclaimed wood and placed an antique potter’s stand, which looks like farm machinery, alongside a clean-lined sofa.

Another group is the New Traditionalists, who, Dellatore writes, “pay homage to classic design while responding to societal changes.” David Kleinberg already was a New Traditionalist when he left Parish-Hadley, in 1991, and founded David Kleinberg Design Associates (DKDA). Now, his young partners have followed suit. Among them is Matthew Bemis, whose work has both visual and tactile richness. “Every room needs a bit of leather or suede,” Bemis says in the book. “And metal details, whether in the architecture or on a piece of furniture. It adds a jewelry-like quality to the space.” Partner Lance Scott, who takes inspiration from fashion designers like Christian Dior, Oscar de la Renta and Valentino, tells Dellatore that he likes “crisply tailored upholstery with discreet dressmaker details.”

Left: In the dining room of a pied-à-terre designed by Tina Ramchandani in New York’s West Village, a Lee Broom pendant lamp hangs over a round table and the cognac-colored leather armchairs that inspired the space’s palette (photo by Jacob Snavely). Right: Caleb Anderson — partner with Jamie Drake in the firm Drake/Anderson — hung a Gabriel Scott chandelier in another New York City dining room, this one described by Dellatore as reimagining the classic blue-and-white color scheme (photo by Brittany Ambridge/OTTO).

Still another New Traditionalist is DKDA partner Scott Sloat, whose explorations of fine craft include a chrome and ebonized mahogany bed and a set of dining-room chairs upholstered in woven horsehair. Asked his trademarks, Sloat lists “a mix of humble and luxurious materials: good woven textures, striped fabrics, great taffeta, contrast welts on upholstery and custom furniture.”

Lucinda Loya used what Dellatore calls “a joyful riot of shapes and colors” to welcome guests in the foyer of a house in Houston, where she is based. “The linear-patterned wallpaper,” Dellatore writes, “accentuates the hardware of the custom credenza.” Photo by Julie Soefer

But these are new traditionalists, as proved by the edgy black leather skirts Sean Matijevich, formerly of DKDA, gave a pair of console tables in a Manhattan living room boasting artworks by Donald Judd, Andy Warhol and Gerhard Richter.

Stanford-educated Dan Fink, whom Dellatore labels a devotee of Masculine Restraint, began his career in design as an executive assistant planning retreats for his boss. Now, he has clients who can afford Pablo Picasso paintings but don’t want their houses to look like art museums. In one San Francisco living room, Picasso’s Jacqueline au Bandeau hangs above an Andrée Putman settee, while in the bedroom a pair of Ansel Adams photos are displayed alongside a table by the Swedish master Axel Einar Hjorth — obviously, not all the big names are hanging on the wall.

In a garden-level Brooklyn bedroom, David Kaihoi, Miles Redd‘s partner in the recently formed firm Redd Kaihoi, deployed a Jean Royère–inspired bed, Moroccan rugs he cut to fit the space and the Weeping Pine wallpaper that he designed for Schumacher. Photo by Jaka Vinsek

Another group of interior designers, whom Dellatore calls the Saturated Colorists, embrace going bold. Kati Curtis, who is based in New York and Los Angeles and names Tony Duquette as an influence, believes no room should be without indigenous textiles, including Indian silks and Balinese ikats.

Back in the alpine-inflected New Jersey home designed by Wesley Moon, a vintage Mazzega glass floor lamp by Carlo Nason (which Moon found on 1stdibs) sits between a John Saladino settee and a 19th-century Louis XVI–style chair with its original Aubusson panel. Photo by William Waldron

Other designers prefer to create symphonies of neutrals, as Wesley Moon, a New Traditionalist, did in one of the most exciting spaces in the book: a great room (in every sense) in a New Jersey mansion. Alongside existing rubble-stone walls, Moon commissioned a mural in muted tones by MJ Atelier to serve as a backdrop to a John Saladino settee, a 19th-century Louis XVI–style chair with an original Aubusson panel and a vintage Mazzega glass floor lamp by Carlo Nason, purchased on 1stdibs. All these pieces, placed on a white fur rug, are quietly complementary. “I don’t like when there’s one piece in a room screaming at you,” Moon told Introspective in 2017.

But if the designers in the book fall into different categories, they all have one thing in common: a love of foreign travel, sometimes to shop but other times to be inspired. Consider saturated Colorist David Kaihoi, Miles Redd’s recently appointed partner in the firm Redd Kaihoi. “I visited Petra, in Jordan, once as a student many years ago,” he tells Dellatore, “and have never really recovered.” What he found so moving was the unexpectedness of classical architecture carved into geological forms. Kaihoi tries to capture that sense of the unexpected in his work. This often means breaking with accepted norms. In designing with art, for example, he advises, “never mind strict rules about height or hierarchy.” And then, continuing with a suggestion that might have come from any one of the members of Dellatore’s On Style cohort, he concludes, “Trust your gut.”

Buy the book.

Or support your local bookstore.