October 20, 2022Chris Mitchell and Pilar Guzmán know their way around magazines: He was the publisher of Vanity Fair, the New Yorker and GQ, among other titles; she was the editor in chief of Condé Nast Traveler, Martha Stewart Living and Cookie. Turns out this media power couple (they’ve been married for 20 years and are the parents of two sons) also know their way around houses — and the wonderful vintage and antique furniture and objects that give those houses style, substance and soul.

Design obsessives and serial renovators, Mitchell and Guzmán have honed their aesthetic through six home redos (they’re currently working on their seventh), perfecting the act of give, take and mutual respect that characterizes the best marriages — and design projects.

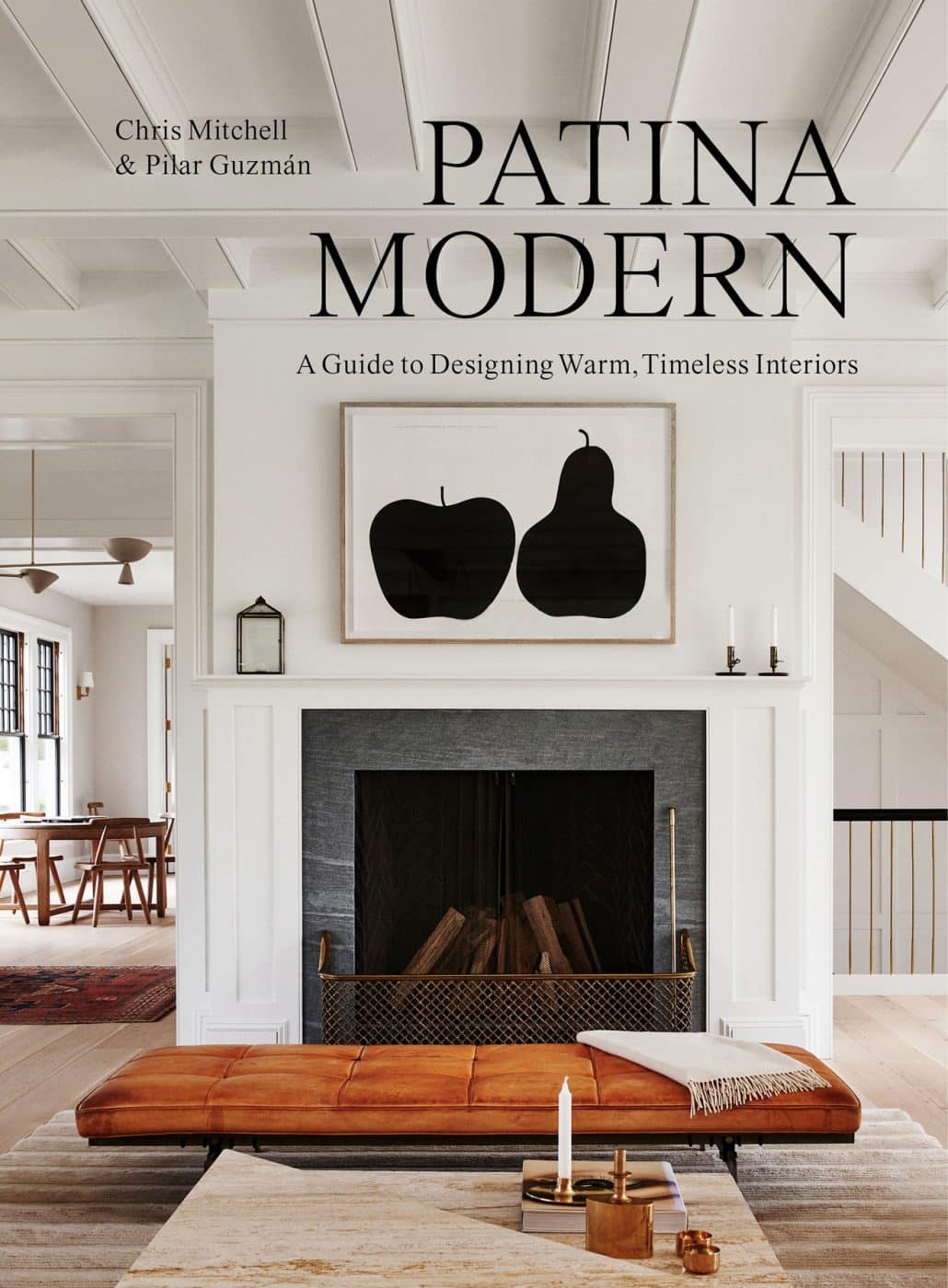

Proof of their fertile partnership can be found in their new book, Patina Modern, which showcases three houses they’ve called home: two classic Hamptons “cottages” and one beguiling Brooklyn brownstone. Through it all, Guzmán writes in Patina Modern’s introduction, “[o]ur projects have been influenced by two things: a passion for twentieth-century design, and the groundbreaking work of our favorite designers,” whose contributions are celebrated and explicated on practically every beautiful page.

Having opened the doors to their homes in the book, Mitchell and Guzmán open a window here into their creative collaborations and shared love of great design.

How do two highly opinionated and design-savvy individuals come to agreement?

Pilar: We sorted out most of our design differences early on in the relationship. I grew up in a historic house filled with European antiques. Chris, who had a very suburban childhood, aspired to an eighties modernism he’d learned from books and movies. We came with very different reference points. When we first moved in together, we didn’t have any choice but to combine our respective hauls from the Twenty-Sixth Street flea market. At that age, we didn’t have the luxury of starting from scratch. We made do with our combined furnishings, each making the case for our beloved pieces. What we ended up with blended surprisingly well.

Chris: It’s true. When we met, I had a vision of adulthood that looked like Bright Lights, Big City — a Soho loft filled with chrome-and-leather Mies van der Rohe pieces. But Pilar’s eye — thanks to her late father, who was a genius collector — went for the worn and imperfect. And I think my biggest revelation was realizing that the modern looked even better next to the old (and vice versa). It’s the lesson our friend architecture critic Paul Goldberger famously taught about the takeover of modernism in midtown Manhattan: the steel-and-glass skyscrapers looked way more amazing when they were reflecting older stone buildings. When they only reflected other glass buildings, that contrast was lost. Today, that mix is our mantra — we never want too much of any one period, and we love the relationship that different periods and styles have to each other. After all, they’re all playing off the same historical influences, just at different points in time and place.

What do each of you love that the other one hates?

Chris: Neither of us is a huge fan of bold color or pattern. But I’m definitely more averse to maximalism than Pilar. I think it’s because I’ve seen color used so badly that it can really ruin a room, whereas a neutral palette is much more forgiving. My love of all things minimalist drew me initially to white rooms, whereas Pilar’s love of antiques made her much more drawn to darker and deeper hues. I am also clearly the more OCD of the two of us. So, a nearly empty John Pawson space, where the objects are hidden away and the few pieces of furniture are treated as heroes, really speaks to me.

Pilar: I love a well-placed English floral chair, or a daybed upholstered in a colorful crewelwork, or embroidered textiles from places like Chiapas or Kashmir. Chris appreciates those things in other spaces, just not ours! On the other hand, Chris is always trying to get me excited by some Biedermeier chest of drawers or secretary. And while I appreciate the refinement and craftsmanship of these pieces, they aren’t my jam at all.

What have you each learned to love, thanks to the other?

Pilar: I learned from Chris that good design is as much about subtracting stuff as it is about layering. And that there is value in the pairing of the hard edges that he was so fond of in our early years and the curves of, say, an eighteenth-century English bench. It’s the push-pull between modern and traditional, hard and soft, nubby and sleek that has become our true north. Also, he taught me that just because we arranged a room one way and liked it for a time doesn’t mean we can’t rearrange it the next month. The eye always evolves — as do the needs of a family.

Chris: I learned a dollop of practicality from Pilar. My sin is definitely form over function, and she course-corrects me so we have enough food-pantry storage, comfortable seating and other things humans need for actual living. If left to my own devices, we’d be living exclusively with daybeds, open shelving and tatami mats for sleeping. Kidding, not kidding.

What was your biggest argument that you still regret?

Pilar: Not having stretched to buy a classic-six apartment in Chelsea’s London Terrace way back before we had children or were even married. It was a magical corner apartment with the building’s famous stone gargoyles perched outside its windows. I have always been much more financially conservative than Chris, and I couldn’t bring myself to bet that big, given where we were in our careers. In hindsight, we should have taken a “beg, borrow and steal” attitude. It would have been an incredible home to start a family in.

Chris: It wasn’t so much an argument as the one time financial reason won out. I tend to be the “magical thinker” when it comes to real estate purchases, while Pilar is definitely more sane. This was the first, and perhaps only time thereafter, where she convinced me we couldn’t do the mathematical acrobatics to buy a place we wanted. And she was probably right that it would have bankrupted us! But wow, do we look at that corner of Ninth Avenue and Twenty-Fourth Street to this day and wonder what it would have been like to live in all that prewar glamour.

What was your biggest argument that ended in the best compromise/solution?

Pilar: Because we didn’t buy that London Terrace apartment, we ended up in a Victorian “estate condition” floor-through in Chelsea. It was in this nineteenth-century fourth-floor walk-up that we did our first gut renovation, a sort of precursor to our Brooklyn brownstone of a similar vintage. We learned that you can create modern interiors in traditional shells — even ones with ornate mahogany moldings. Plus, given its Miss Havisham condition, no other prospective buyers seemed to have a vision for it, which astounded us. I remember at the open house shushing Chris over his enthusiasm for the intact parquet floors and moldings underneath one hundred and fifty years worth of sloppy paint jobs.

Chris: That’s a good one, and the other lesson that experience taught us was that anything is possible when it comes to gut renovating. When we found a house in East Hampton, years later, that looked about ready to cave in, we had just enough experience, courage and foolishness to tackle it. It required lifting the entire house in order to put in a new basement and foundation. To us, this was a total miracle. But we realized that, like that other miracle called childbirth, it’s a pretty routine operation to the pros. Now, when we consider taking on an old house, no matter how terrible its condition, we’re like, “No problem, we do that.”

Regarding the things about which you’re in complete agreement, who are the makers — furniture designers, artists, ceramists, glassblowers, silversmiths — you love most?

Pilar: In no particular order, the iconic and hardworking chairs of Hans Wegner and Finn Juhl, for their sculptural quality and rigorous craftsmanship. And then, there is also Poul Kjærholm, whose PK80 daybed in original, patinated vegetable-tanned leather is still the holy grail.

Chris: Florian Schulz, a German lighting designer, whose brass double chandeliers are like jewelry. And any object by Carl Auböck, because they’re the perfect combo of craft, elegance and whimsy.

What’s your favorite room out of all the rooms featured in the book?

Pilar: Our kitchen in Brooklyn, as much for what twenty years ago felt like a magic trick — sneaking modern appliances and an island into a formal nineteenth-century back parlor — as for its utility. With a tufted leather banquette and gas fireplace, it is easily the hardest-working room in the house and holds what I’d put at about eighty percent of our family history.

Chris: The Brooklyn kitchen is hard to beat. And since it was covered, in 2006, in the New York Times, we swear that it spawned an entire generation of kitchen renovations. But I’d also submit the kitchen in our Bridgehampton house. When we were designing this house, and adding a whole wing onto the original 1700-era volume, the kitchen became this corner room that connected the living room on one side and the dining room on the other. So, it basically had no interior wall for traditional kitchen stuff like cabinets. Our solution was to put one large, eight-part window on the back wall and then commission a brass-and-glass china cabinet in front of it. It’s frankly a showstopper — about a hundred square feet of Rosenthal porcelain, barware and favorite objects, all backlit by western light. At sunset, it’s pretty magical.

How is building and furnishing a house together a metaphor for building a marriage and raising a family?

Pilar: When you meet when you are young and essentially grow up on each others’ watch, the ways in which you influence one another are more incremental than intentional. (Intentionality comes much later!) Being open to a different aesthetic or different artists, designers and ideas is really a study in vulnerability. That is to say, there is no right answer when it comes to matters of taste, especially when it’s between two alpha aesthetes. Just like there is usually no one right answer when it comes to a marital dispute — there are only points of view.

Building a home together is a lifelong practice in openness and a willingness to make micro changes along the way. Let being proved wrong be a feather in your cap. Putting our kitchen in that back parlor in 2003 seemed like blasphemy at a time when everyone considered those grand parlors sacrosanct. In my mother-in-law’s infinite wisdom, when we were about to refurbish the existing kitchen on the second floor, she reminded us that families only really ever live in one room. If we hadn’t moved our kitchen to the parlor floor, that space probably would have become one of those unused living rooms of our parents’ generation, the kind you only ever entered when you had company over.

Chris: We joke that we fight about everything (I swear, including which side of the street to walk on), but never about renovation or design. And I think that’s because we both know, as more or less obvious control freaks, that there isn’t a right answer to design. The fact that it’s a dialogue, and also that it’s constantly evolving, makes for a give and take that I wish we had in all the other parts of our relationship. Marriage and parenting are often hard, and the bad decisions you make hurt people. But in design, the do-overs are actually pretty easy and usually without dire consequence. I think the challenge most people have in design is the fear of commitment, which is really the fear of regret. But if we have learned anything, it’s that your limitations and mistakes often create unexpected beauty. So, have fun with it, and never forget that you have the great fortune of living your life in this home you’ve created. We have found that the hard stuff is a bit easier when we’re enveloped by things we love, things that have meaning and memories and thereby connect us as a family.