April 4, 2021At Robert Simon’s Manhattan gallery, a pair of small jewel-toned Renaissance paintings — of Saint Vincent Ferrer and of John the Baptist with Jesus Christ — are displayed like family photos, angled slightly toward each other on a console table.

The pale linen walls of the handsome space, located in a 1920s townhouse less than a block from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are hung with other similarly splendid Old Masters: clever trompe l’oeil still lifes, glowing landscapes and portraits that gaze back at the viewer with striking humanity. Simon’s keen eye and expertise have won him an international reputation for bringing to light such treasures — including the Leonardo da Vinci painting he discovered at an estate auction in New Orleans in 2015.

Unlike many Old Master dealers, Simon didn’t grow up in the business. Born and raised in New York City, he discovered his love for art as a student traveling in Europe, going on to earn a doctorate in Mannerist painting from Columbia University in 1982. “My parents thought it was pretty weird, what I was doing,” he admits.

Four years later, while Simon was working as an independent appraiser, Old Master dealer Piero Corsini requested his help researching a painting he had donated to the Met. Impressed with Simon’s expertise, Corsini offered him steady employment with his gallery. “From there it was all downhill,” says Simon. “Or uphill, depending how you look at it!”

His own career as a dealer began somewhat accidentally, when a collector for whom he had purchased a work at auction and organized its restoration ran into financial problems. “He couldn’t pay for it, and he didn’t pay me either,” recalls Simon, who sold the work to Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum instead.

That experience lit the spark. In 1997, Simon reluctantly sold a watercolor from his personal collection, by Victorian painter Richard Dadd, and opened a gallery in his apartment on New York’s Upper East Side. He specialized in the works that he was most passionate about: Italian, French and Spanish paintings from the baroque and Renaissance periods.

Although prized by museums, these pieces were often neglected by collectors, who simply were not aware of their accessibility and availability. “For the price of a contemporary print, one could buy a significant work five hundred years old,” Simon observes. “And even today, with increased attention in the field, Old Masters still represent a unique opportunity to enjoy a painting of great beauty from the past that has resonance in the present.”

It was a 2005 auction in New Orleans that marked the highlight of Simon’s career to date. Along with friend and colleague Alexander Parish, Simon had spotted an intriguing work among the lots and suspected that a piece of real quality, perhaps by one of Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci’s “able and talented followers,” might lie under its layers of overpaint.

Anticipating that the painting would sell for a significant amount, they decided to join forces to purchase it. As it turned out, the pair needed only to beat a single bidder for the small panel, buying it for a mere $1,150.

“What followed was eight years of focused research here and abroad, expert conservation, technical analyses and consultations with the leading curators and scholars in the field,” says Simon. The determination: The work, a magnificent rendering of Jesus assumed to be a copy of Leonardo’s long-lost Salvator Mundi, was in fact the original and the last known painting by the artist still in private hands.

How did Simon feel when he realized he was working with a Leonardo? “Scared.”

He needn’t have been. In 2013, he and Parish sold the painting for a reported $80 million. Four years later, another owner offered it at Christie’s, where it smashed records, selling for $450 million. Still, Simon doesn’t regret letting it go. “To have a chance to own a painting like that, to keep it, is one thing,” he says. “But even to have it for a while is a treat of a lifetime.”

With his gallery currently closed because of the COVID shutdown, Simon is relying more on digital initiatives, he says, such as online catalogues and platforms like 1stDibs.

One silver lining is that the pandemic has given him more time to work with museums than in the past, and the intensive research requires him to spend long hours in the two-story library at his house. He spoke with Introspective from his book-lined work-from-home space about the art that is his passion.

What first attracted you to Old Masters?

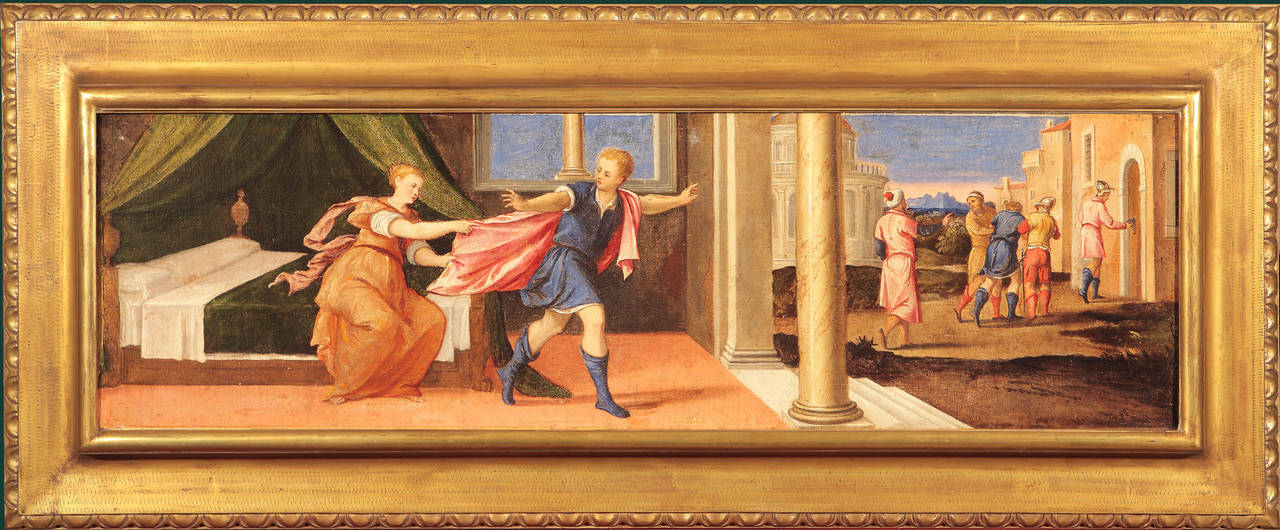

One enters a different world entirely. These paintings have different contexts — whether historical or religious or cultural — that are great windows into the past. People may not at first think of Old Master paintings as having strong emotional content, but they often do, especially Italian works. Antonio Palma’s painting Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife is a lovers’ drama in miniature, with an impassioned woman and a reticent man.

What is the Old Master market like these days?

There is increasing interest. There’s this fear that if it’s not attracting twentysomethings, it has no future. But it requires an older audience, people with more travel, more experience, more knowledge.

As people learn about it, they are surprised to find that not only are these pictures available, but they are available at prices lower than those you find in contemporary art. Plus, values have not dropped in any way during the years I’ve been working in it. They’ve gone steadily upward, in a very rational way.

Are certain subjects or artists especially popular now?

Women artists from the Renaissance through the nineteenth century who have been overlooked, such as Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann, are getting attention. Also Spanish colonial art has had a great response from collectors attracted to the rich ornament that characterizes paintings, sculpture and objects of the period. They combine the influences of traditional Spanish culture with the vitality of the indigenous arts of the Americas, as seen in the painting Our Lady of Solitude or our elaborate silver Peruvian baptismal dish.

How can buyers protect themselves from fakes?

It sounds self-serving, but by buying from a reputable dealer. A picture from the sixteenth century whose condition has been compromised or that’s been repainted in whole or in part can be challenging to judge, especially today when you’re looking at it digitally. But dealers can help and generally like to share their knowledge and experience.

You can also consult independent scholars or, if you become interested in the field in the long term, educate yourself. My best advice there is to start in a museum and wander.

Are interior designers interested in Renaissance works and Old Masters? What do they look for when they seek these pieces out?

There are two groups of designers who pursue Old Masters for their clients. One is seeking works that are appropriate and harmonious in a traditional interior. The other is looking for exactly the opposite — a painting that will serve as a bold contrast in a contemporary or minimal design.

Is there subject matter that tends to be more valuable?

Traditionally, the more sought-after works for collectors are still-life paintings, landscapes, architectural views — particularly of Venice — depictions of horses and dogs. But the more valuable ones, and the ones that are prized for investment purposes, are simply those of the highest quality, by the most significant artists, whether they’re “easy” or “difficult” subjects. A gritty old man by Rembrandt will prove to be a better investment than an Arcadian landscape.

What piece currently on 1stDibs exemplifies the kind of material you gravitate toward?

Hard to answer, as I like so many things, but let me choose Domenico Tintoretto’s Portrait of a Young Lady. This is an honest, immediate and charming depiction of a woman, painted directly from life, and one that allows us to have a kind of conversation with someone from sixteenth-century Venice. Amazing!