February 18, 2024When my editor sent an email asking what I thought of the art of Walasse Ting, I replied, “It’s like Warhol meets Matisse!”

Well, I got it partly right.

The Matisse connection runs deep. In many of his paintings, especially his nudes, Ting looked to the Fauvist master for inspiration. And in an even more personal homage, he spelled his chosen Western name, Walasse (pronounced like Wallace), with an -sse. It’s as though he saw himself as the successor to the modern-art giant, who died in 1954, not long after Ting invented his nom d’artiste.

As for Warhol, although it’s true that Ting went through a Pop art phase in the 1960s and ’70s, he experimented in a range of genres throughout his half-century career, including Action Painting, Expressionism (abstract and figurative), Chinese ink painting, postmodern poetry, poster art, book art, fashion design and more.

While he never rose to the mainstream level of Warhol or Matisse, the gregarious, dapper Ting was a major player in the art world in his heyday, showing at the legendary Martha Jackson Gallery in New York, landing works in the most-visited museum collections and collaborating with the biggest artists of his time.

Nevertheless, he faded from the American art scene after the 1986 shuttering of Lefebre Gallery, which represented his art for more than 20 years.

Now, a pair of exhibitions in the United States puts Ting back in the limelight as a major artistic force. Venerated Hong Kong gallery Alisan Fine Arts recently inaugurated its Manhattan outpost with “Walasse Ting: New York, New York,” spanning five decades of Ting paintings with an emphasis on his New York years.

And the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale has put together the first U.S. retrospective of the Chinese-American artist, “Walasse Ting: Parrot Jungle” (through March 10), displaying Ting’s personal photographs, quirky postcards and paint-encrusted brushes alongside his exuberant paintings, drawings and prints. That show plays up his connection to Florida, where he spent many Februarys visiting his in-laws in West Palm Beach and taking photos of the garishly feathered macaws and flamingos in the Parrot Jungle animal park, which he later turned into paintings in his chilly New York studio.

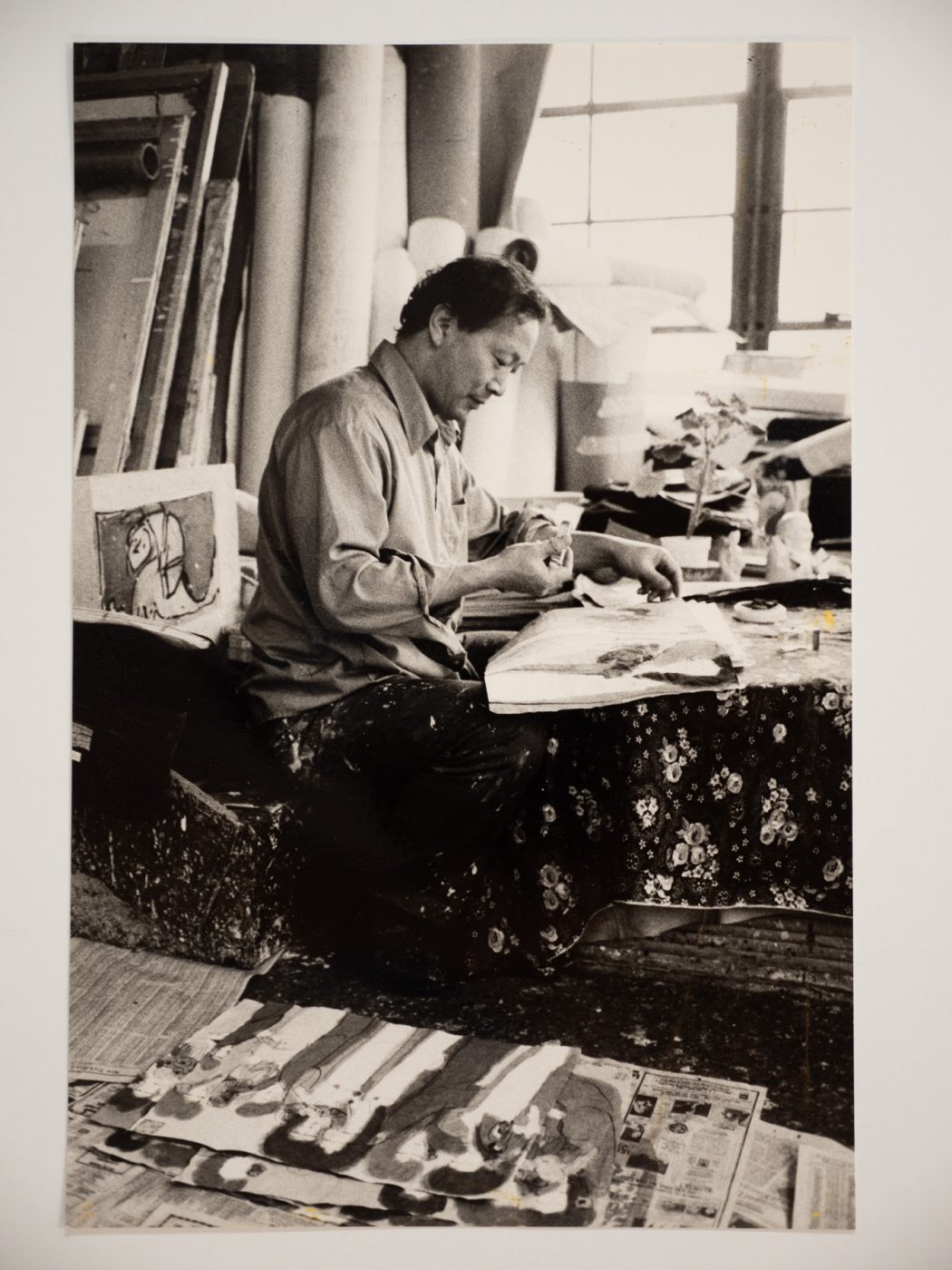

Walasse Ting was about as cosmopolitan an artist as you will find. Born Ding Xiongquan on October 13, 1928, in Wuxi, China, and raised in Shanghai, the self-trained painter and poet went on to live and create in Hong Kong, Paris, New York and Amsterdam in the decades before his death in 2010. “All these places fed him, physically — he was a huge gourmand — as well as spiritually and artistically,” says his daughter, Mia Ting, who oversees his estate.

“Ting was impacted by the art historic traditions of each place, as well as the work of pioneering artists around him,” adds NSU Art Museum curator Ariella Wolens. “So, when he’s growing up in and around Shanghai, it’s Chinese traditional culture. In Paris, it’s CoBrA and the European avant-garde. In New York, it’s Pop and action painting. He weaves all these inspirations into his own fiercely independent language.”

You can see his work progress from inky chariots during his Hong Kong years, in the early 1950s, to art brut and expressionistic musings a few years later in Paris, where he collaborated with CoBrA (Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) artists such as Pierre Alechinsky and Karel Appel, to monochrome and then technicolor action paintings after he relocated to New York, in 1963, and befriended Sam Francis, to the Pop-inflected consumer products and fashionable women he portrayed after meeting Tom Wesselmann and Claes Oldenburg.

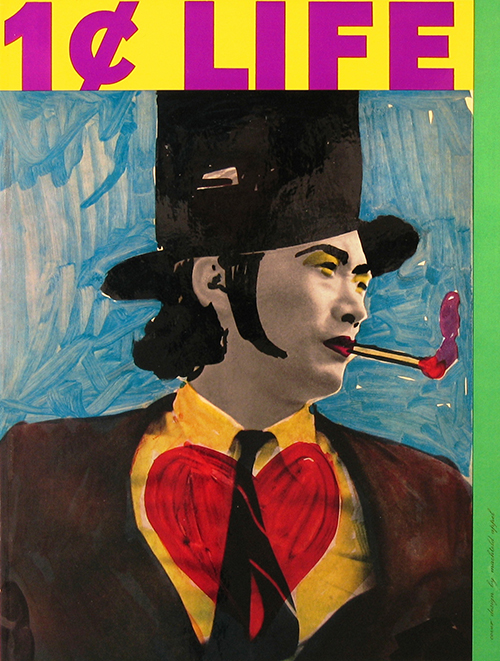

Ting’s most famous creation, the art book 1¢ Life (1963), merges all these influences. In it, Ting pairs his subversive, bawdy poetry with 27 illustrations by Alechinsky, Appel, Francis, Joan Mitchell, Jim Dine, Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, Wesselmann, Warhol and many other budding luminaries of the era. Who else but Ting would think to put together European avant-gardists, second-generation Abstract Expressionists and Pop artists? “You can’t even use some of these artists in the same sentence,” Mia quips. But the combo somehow works.

“The irony, of course, is that the reason Ting conceived of 1¢ Life was as a vehicle to promote his poetry, thinking that a book with works by all these world-class artists would get his name out as a poet,” says Nadine Witkin, director of Alpha 137 Gallery, which has a signed lithographic edition of 1¢ Life that was formerly owned by Robert Indiana, who also contributed to the book. “But over the years, nobody took notice of Ting’s text, and most collectors and dealers of the lithographs aren’t even aware of the poetry that accompanied them.”

Ting would end up spending the majority of his life in New York. There, he met and married Natalie Lipton, a commercial artist from Brooklyn who became the grounding force in the relationship and with whom Ting had two children, Mia and Jesse. “Ting’s wife was a classic New Yorker, born and raised in Crown Heights to Jewish parents, who when they retired, moved down to West Palm Beach,” Wolens explains.

“My dad loved my mother’s family,” says Mia. “Chinese families tend to be very formal, and Jewish families tend to be very effusive and affectionate, and he loved it.”

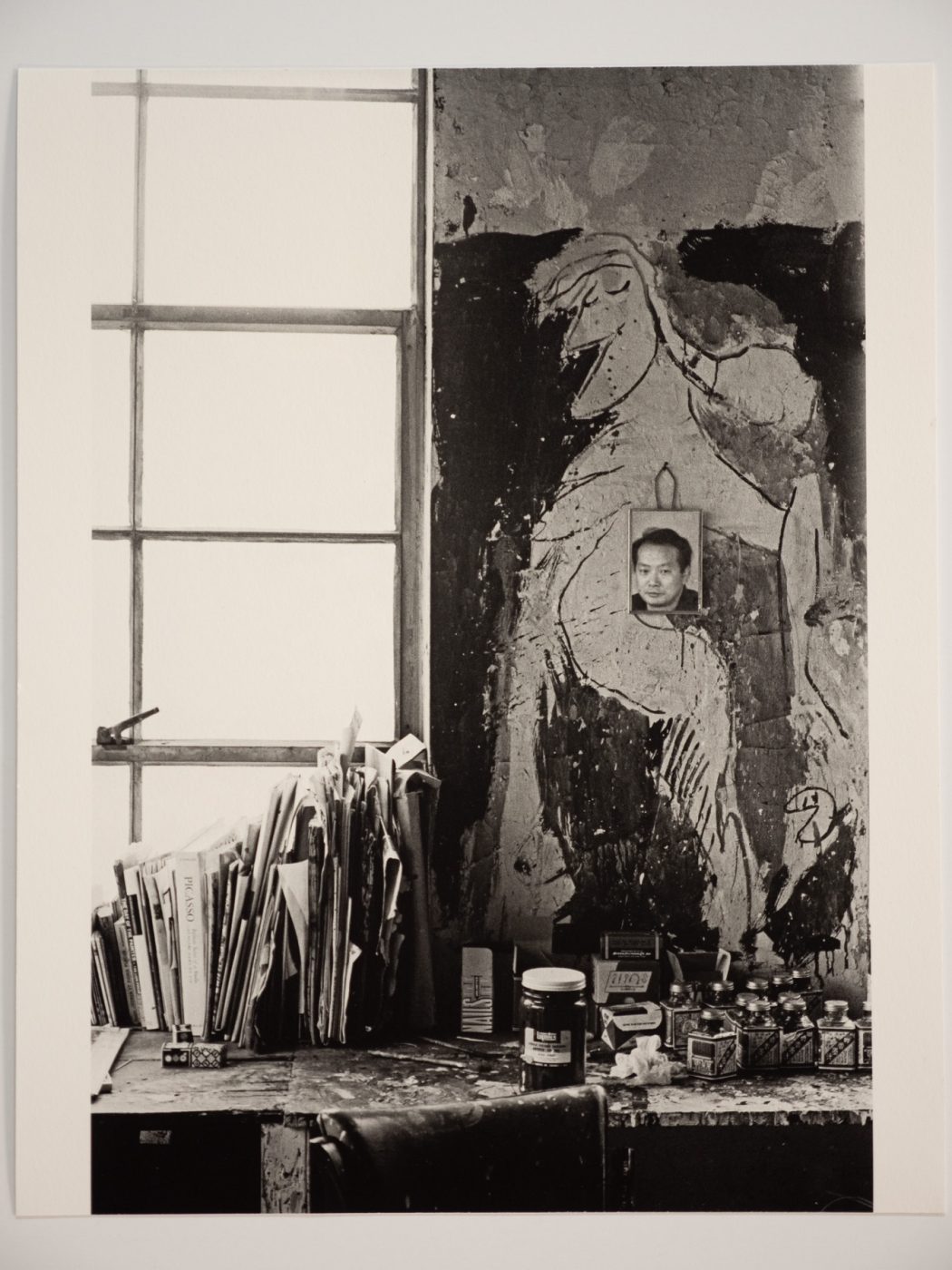

“Ting is such a fascinating character, and to me, the way he lived was part of his art,” Wolens notes. “He was a collector and a total maximalist, which you also see in his paintings. The family has floor-to-ceiling collections of his porcelain figures, jade charms, fountain pens, brushes, suits, watches.”

He enjoyed dressing up, even painting in tailored suits. “I never saw him wear jeans once. He never wore sneakers,” Mia says.

Remarkably, Ting never abandoned any of the various styles he worked in, and some of his most striking compositions pull them all together. So, in several of his 1970s paintings, such as Raindrops on My Eyes (1974), Love Me With Your Heart That I Want (1975) and Miss World (1975), you see bare-chested women limned with bold Pop outlines and covered in loose, electrifying AbEx splatters.

By the 1980s and ’90s, in My World (1985) and his many untitled works, he was blending Chinese ink with vivid acrylics on rice paper and merging scenes of Floridian fruits and parrots with Song and Tang dynasty–style horses and Japanese geishas; he even started stamping his art with a Chinese red chop.

For many reasons, in the 1980s, Ting ceased to influence the New York art zeitgeist. There was the aforementioned closing of his gallery, as well as the 1983 death of Natalie. “After my mother died, my father was heartbroken and depressed, and spent much more time away from New York,” Mia says.

My World, 1985, is a fantastic amalgamation of the kind of work Ting was creating in the ’80s. Photo by Jeffrey Sturges © The Estate of Walasse Ting

There’s also the fact he cannot be pigeonholed. Ting was an artist who belonged to no single movement or nation, making the narrative of his career messy and complicated. As Mia points out, he couldn’t really be lumped in with the mainland Chinese artists who were gaining steam in the ’80s, but he wasn’t seen as fully American either. “The Whitney [Museum of American Art] did not consider him an American artist,” she says. “He got very upset over that.”

Then, there’s the matter of shifting trends. The disco eyeshadow and big hairdos of his female models, the tropical birds, luscious fruits and trad Chinese motifs, as well as his bombastic colors, likely seemed out-of-place in the austere, culture-war era of the late ’80s and early ’90s. (At the same time, his star rose in East Asia, and his affordable poster art kept him popular in the Netherlands.)

Whistling All Night, 1971. Photo by Jeffrey Sturges

“Ting’s reputation faded as public tastes changed,” says prints dealer Thomas French. “In today’s art market, the renewed interest comes from his timeless imagery combining Chinese painting, CoBrA abstraction and Pop imagery.”

Nowadays, blinding hues and tropical themes feel fresh again (see the popular parrot paintings of Hunt Slonem), and we love re-finding artists from marginalized groups.

“Ting was never a self-promoter, he went where he was naturally embraced,” Wolens says. “Fortunately, the time has been primed for him to reenter the narrative and be remembered for his monumental legacy in the country he called home for most of his life.”