If I ask you to picture a piece of digital art, chances are you will bring to mind a Bored Ape, a CryptoPunk or one of the many famous NFTs currently on the market. But it’s worth remembering that long before the advent of NFTs, the term digital artwork had another meaning altogether.

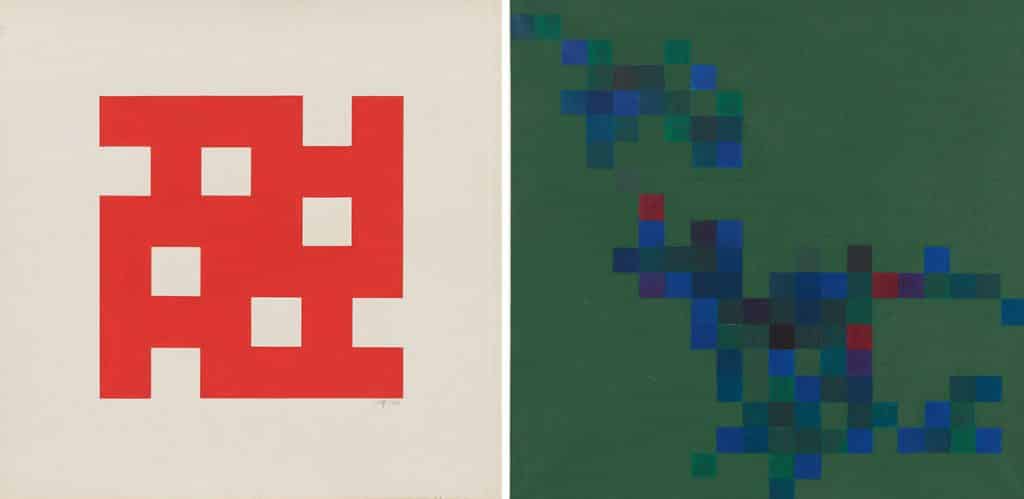

Digital or generative art, as pioneered by artists like Manfred Mohr and Vera Molnár in the 1960s, seeks to blur or even erase the distinction between human and computer-driven creativity, deploying algorithms or artificial intelligence (AI) to generate abstract forms with a life that is independent of the artist who made them.

Both Molnár and Mohr used research computers to produce their early experiments. These were vast machines, designed to make calculations for meteorology or fluid dynamics, that often took up several rooms and produced just a few bytes of computing power. But, for advocates of digital abstraction, their output was free from the taint of human characteristics and, in a sense, purer.

Given the advances in technology in the intervening period, as well as the prevalence of more modestly sized computers in our lives, it’s not surprising that the idea of extending human creativity through machine intelligence should be having a resurgence. Naturally, such pieces, native to digital platforms, are crossing over into the NFT market too.

Anne Spalter has been working in the space for more than 30 years. An artist and educator, she is also the curator (alongside her husband) of the Anne and Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection, the world’s largest private collection of digital works. To this digital artist of standing, NFTs are the long-awaited answer to the question of how to sell her works online, something that was, until now, an anathema to fine art collectors.

Her own pieces often reference the Jungian idea of the collective unconscious, incorporating liminal symbols like spaceships, UFOs or bridges. To create a piece like It Exploded #2 (2021), Spalter briefed a system known as an “adversarial network,” in which two AIs work in competition, one of them absorbing material that has been identified as showing a particular object (for instance “flying saucers”) and attempting to define its character and the other repeatedly trying to produce images that meet the criteria established by the first.

The result is then fed back into the system, creating a series of images which, when minted as an animated GIF, seem to morph or pulsate from form to form psychedelically. Spalter describes the relationship with the AI as “a bit like having a partner in the studio.”

And since these AI image-recognition networks are trained by human subjects on the Internet, they perhaps offer a glimpse into the collective unconscious, that peculiar human ability to recognize diverse objects that we deploy when identifying a grid of traffic lights or buses to prove to a website that we are “not a robot.”

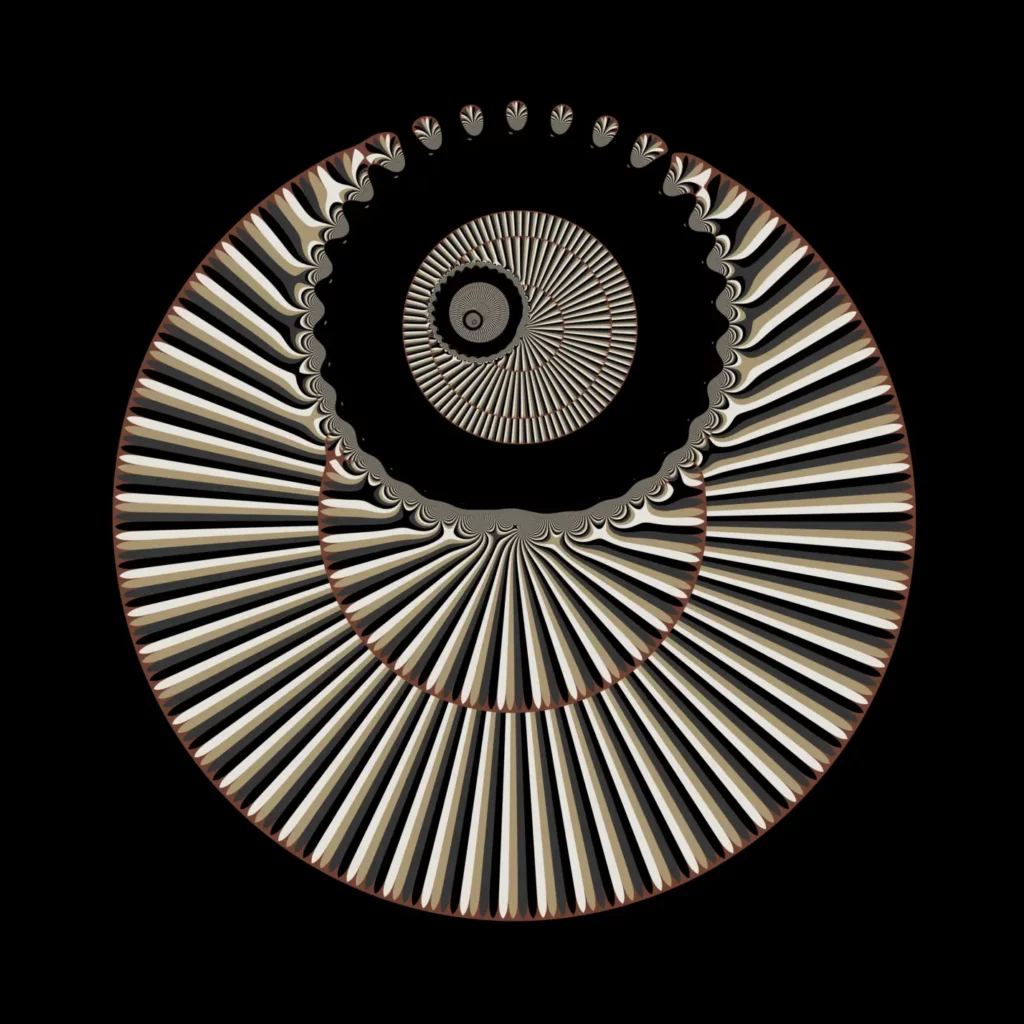

Hungarian artist Daïm Aggott-Hönsch creates mathematical artworks — a field popularized in the 1990s by images of the Mandelbrot Set, an infinitely regressive algorithm that, when plotted visually, reveals more and more complexity with each successive enlargement. Around 15 years ago, Aggott-Hönsch, frustrated by the existing software, began to write his own, revealing forms previously unseen.

To the artist, these visual expressions of numerical relationships represent eternal mathematical truths. “I think back to the time of Plato,” he says, “who viewed mathematical ideas as being, in an odd sense, more real than the reality that we can touch.”

As such, preserving the works on the blockchain makes perfect sense. Not only are they more easily traded, it also parallels their essential permanence in the universe. “I have captured this eternal thing, perhaps for the first time in humanity’s history. So, rather than printing it out and putting it in an Ikea frame, a tokenized NFT feels like it’s a significant step closer to preserving my revelation.”

When he’s not creating these forms on his own software and he wants to polish a few finishing touches through automation, Aggott-Hönsch uses the AI of GAN (generative adversarial networks), which he describes as “collaborating with the guided dreams of fascinatingly complex artificial minds.”

Problems of communication are an obsession of 24-year-old painter and digital artist Sam Price. He laments the ability of humans to fully communicate an idea without the loss of meaning that occurs in the space between consciousnesses. “It’s like when we’re transferring power across the electrical grid,” he says. “You’re always gonna lose some of it.”

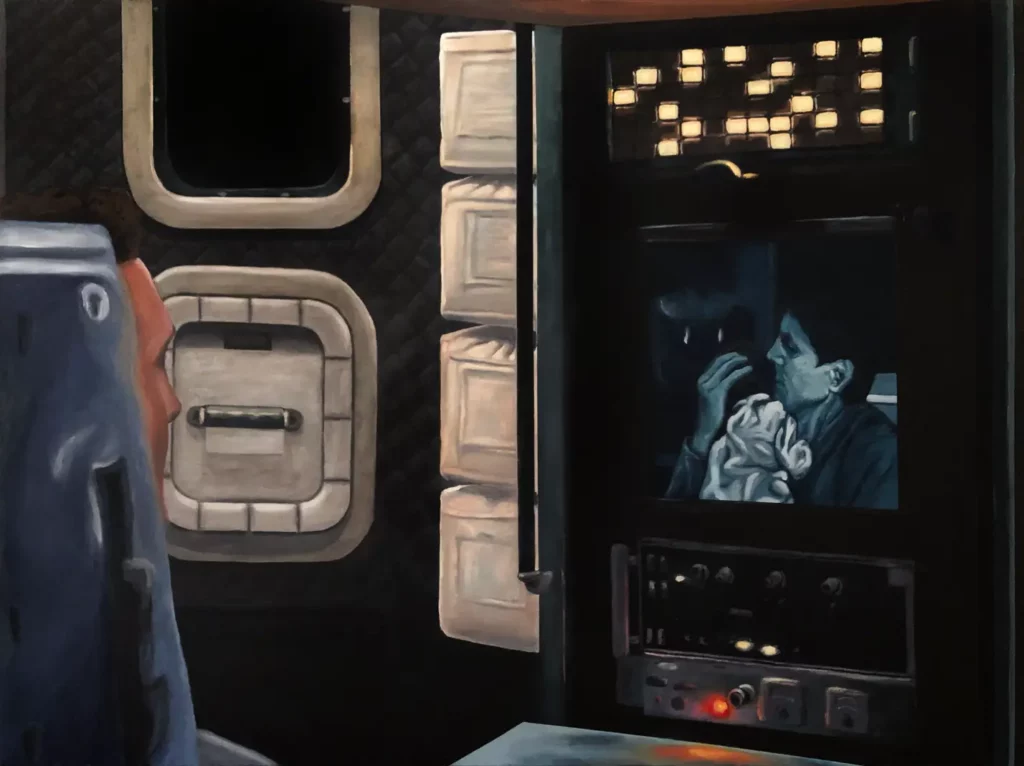

In this, he sounds rather like a digital abstractionist. But rather than exploring the universe of numbers, his domain is outer space, specifically its manifestation in visual culture. “I’m interested in pareidolia, or the tendency of the human mind to see patterns, to see ourselves in the cosmic expanse,” he says.

Price also works in collaboration with an AI, gradually building associations by running images through a neural network over and over. The output is a kind of layered organic topography that is then minted as an NFT. That NFT can then be projected onto an accompanying sculpture to create a hybrid work, a merging of human creative vision, AI and physical sculpture.

If the viewer is reminded of Kubrick’s space-scapes, this is no coincidence, explains Price, who’s a sci-fi fan. It’s an allusion to the human tendency to use art to explore dimensions heretofore unreachable by technology alone.

The projects that currently dominate the NFT space — the Apes, Punks and others — may have taken off partly because they make sense to buyers conceptually. In a way, with their emphasis on limited editions and unique characteristics, they actually help to explain the blockchain to new collectors, defining it in relation to a human sense of our own non-fungibility — that is, despite looking and acting like other people, we feel ourselves to be somehow absolutely particular.

But if such projects have a kind of inevitability about them, they are by no means the only possible use of crypto technology to create works that are conceptually satisfying.

Perhaps artists like Spalter, Aggott-Hönsch and Price, whose work harks back, in some respects, to the pioneers of digital art, offer us a glimpse of what NFTs might one day become. It’s a future straight out of sci-fi, one where human and digital intelligences work hand in hand to produce valuable art that neither could have created alone. Suddenly, it doesn’t feel that far away at all.