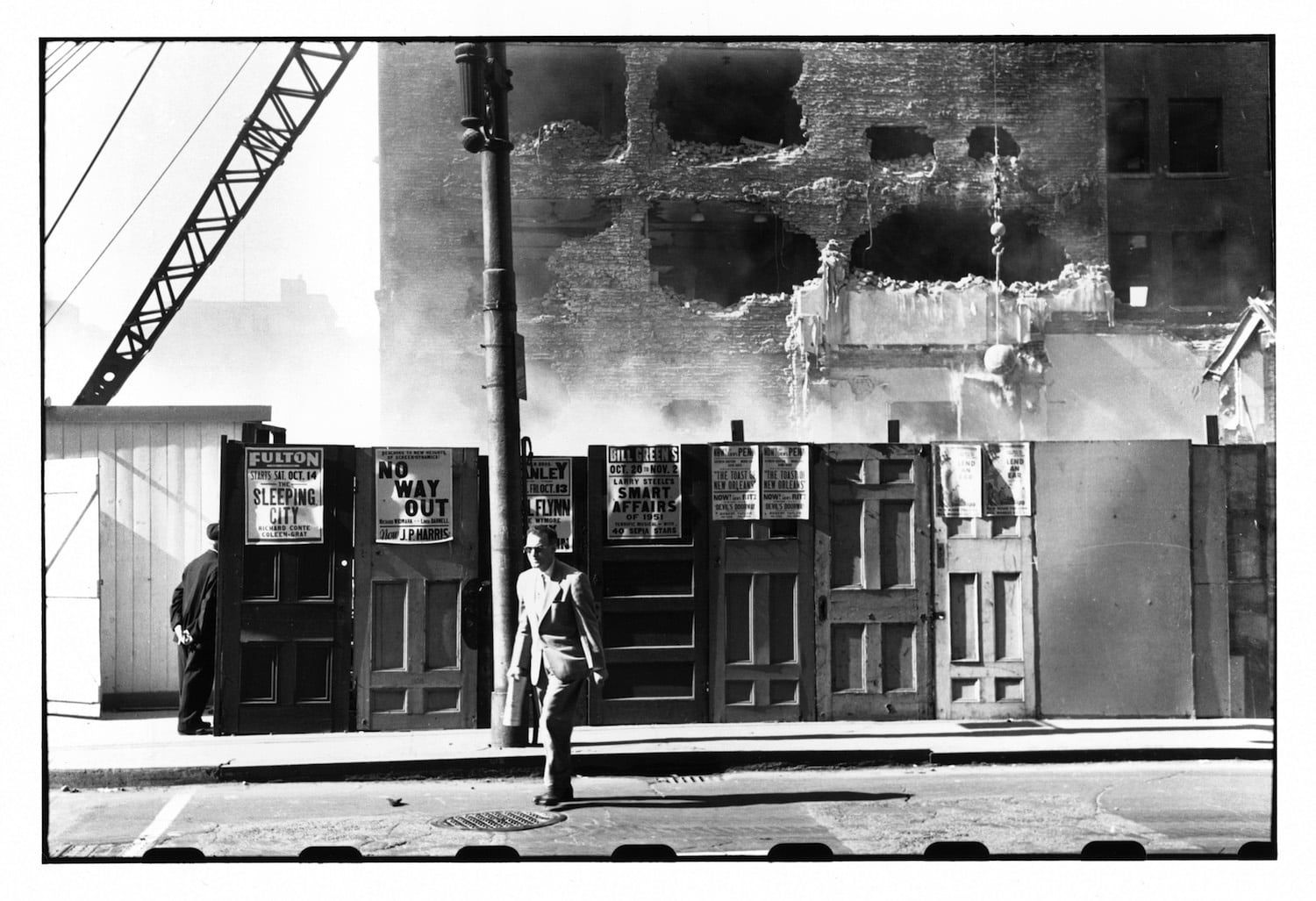

Gateway Center demolition area, Pittsburgh 1950. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos; courtesy of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

This August marked the release of Pittsburgh 1950 (GOST), a collection of previously unpublished photographs taken by the celebrated lensman Elliott Erwitt when he was just 21. He had been tasked with documenting the redevelopment of one of Pittsburgh’s grittier industrial sections by none other than Roy Stryker. Stryker was the estimable former head of the Farm Security Administration’s documentary photography program, which had commissioned the searing images of rural poverty taken by Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange during the Great Depression. Now working for the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, Stryker gave Erwitt free reign to photograph whatever caught his eye.

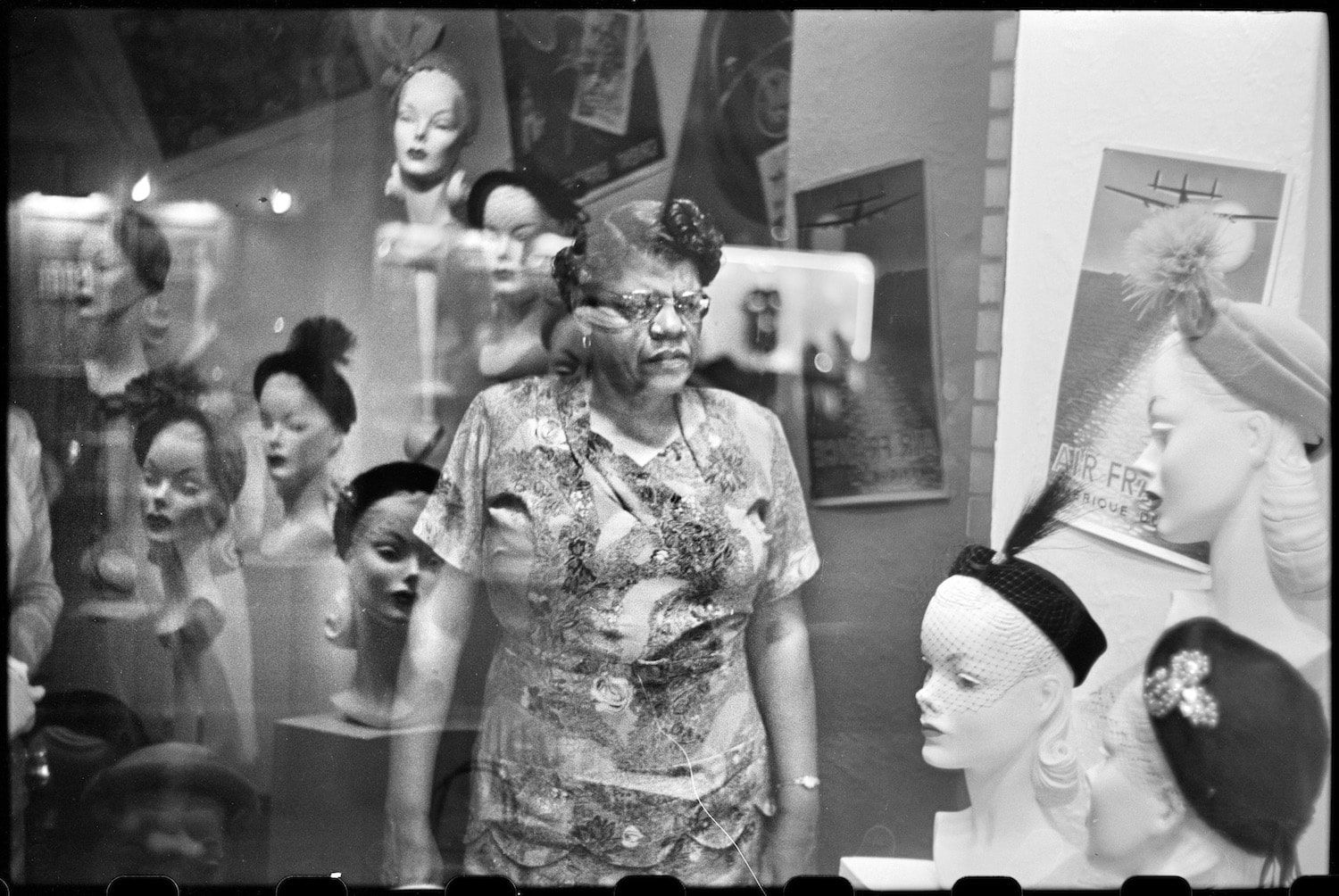

Downtown hat shop window, Pittsburgh, September 1950. © Elliott Erwitt / Magnum Photos; courtesy of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Peruse Pittsburgh 1950, and you’ll see why Stryker had such confidence in the fledgling photographer. In image after image, Erwitt captures what photographers call “the moment” with the rapier wit and penetrating humanity that would make him a legend.

One standout image is of a serious-looking African American woman gazing into a hat shop, surrounded by a sea of reflections of white, patrician-looking dummy heads, each with a stylish hat. It is as visually witty as it is mournfully telling of the racial realities of the day.

The image seems the lost counterpart to another photograph Erwitt took that year in Wilmington, North Carolina, of a young African American man drinking from an old battered water fountain labeled “Colored,” while glancing over at a spiffy new one, labeled “White.” Widely reproduced, it became one of the most powerful indictments of the Jim Crow South during the Civil Rights Movement.

The Pittsburgh project was never completed. After four months, Erwitt was drafted into the Signal Corps of the U.S. Army and sent off to Europe. He kept some negatives, but the one of the hat shop and hundreds of others disappeared. Six years ago, they turned up in Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library. The book is Erwitt’s own selection of the best “snaps,” as he modestly calls his photos.

The photography dealer Missy Finger of PDNB Gallery in Dallas attributes Erwitt’s “extraordinary visual acumen” to his rootless childhood. Born Elio Romano Erwitz in Paris in 1928 to Russian-Jewish parents, the family moved to Milan when he was still a baby. There they lived until 1938, when the political situation forced the family to flee first to France and then to the U.S.

In New York, Erwitt’s parents separated, and he and his father traveled on to Los Angeles. “By the time he was 11,” says Finger, “he spoke Russian, French and Italian. And then he had to quickly pick up English. All these different cultures and languages meant he had to learn a lot visually, which carried him forward in his photography.”

Before graduating from high school in Hollywood, Erwitt had already begun to teach himself to take pictures, inspired by the images of Henri Cartier-Bresson. As he later told his son Misha in a 2011 New York Times interview, what so impressed him about the French photographer’s work was that “a simple observation was all that it took to produce it. I thought, if one could make a living out of doing such pictures, that would be desirable.”

To support himself, as his father had moved to New Orleans when Erwitt was still in high school, he got jobs as a commercial darkroom technician and later a wedding photographer. In 1948, after two years at Los Angeles City College, he moved to New York, and worked as a janitor at the New School for Social Research in a bartering arrangement for film classes.

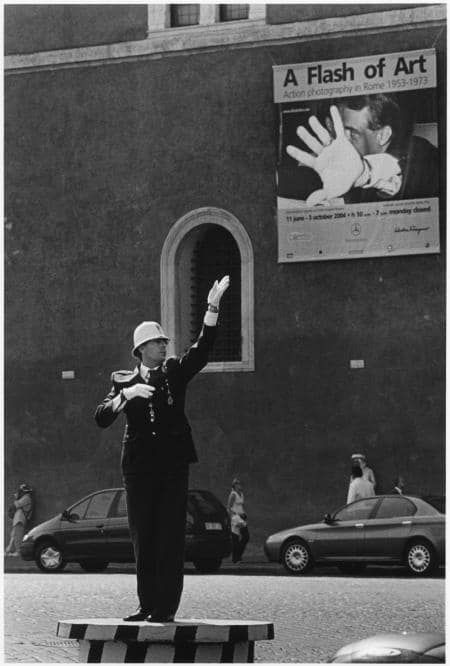

The following year, equipped with a Rolleiflex camera, he traveled to France and Italy. One image taken in Florence proved Erwitt to already be a master of the visual one-liner. In the photo, nude armless statues of a fig leaf-clad man and woman flank an imposing stone archway, where a uniformed guard stands soberly with his white gloved hands over his crotch.

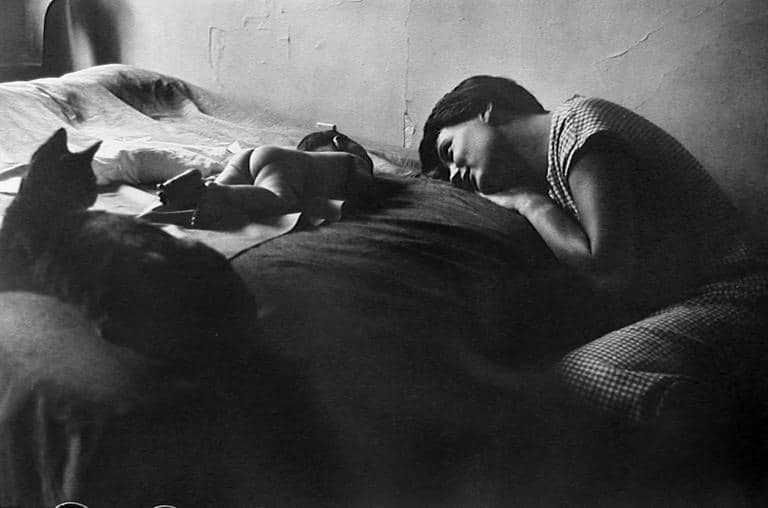

Edward Steichen, then the head of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, bought two photos from the trip, and several years later included Erwitt’s portrait of his wife and infant daughter and cat Brutus in their bare apartment, in his landmark MoMA exhibition “The Family of Man.”

Erwitt also met Robert Capa around this time, and he was impressed enough by Erwitt’s work to invite him to join Magnum Photos when he was discharged from the service in 1953. It was around this time he began using a Leica, at the urging of his colleague Robert Frank, which enabled him to become more spontaneous in his photo taking.

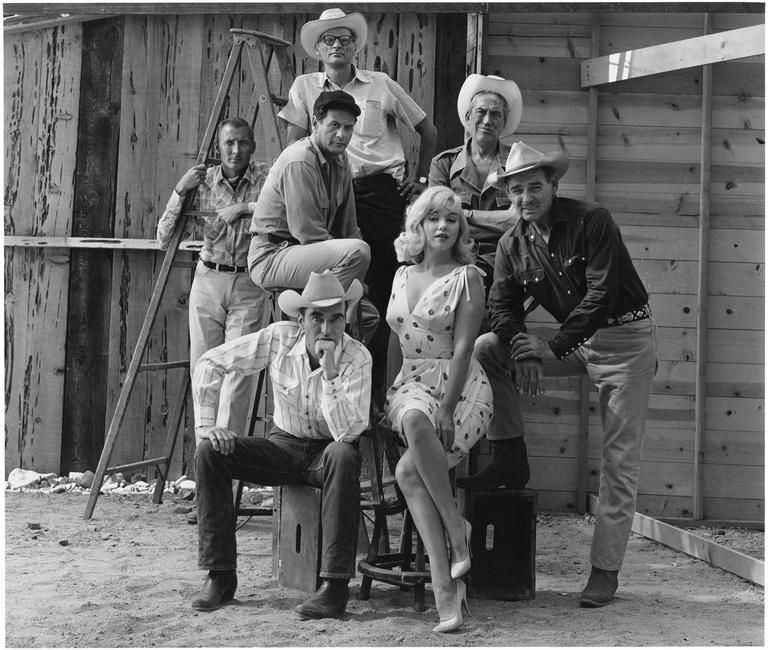

Through Magnum, Erwitt received a vast range of assignments, including shooting movie stars at work and at rest. It was he who took the behind-the-scenes photos of the filming of Marilyn Monroe in The Seven Year Itch, including the famous image of her dress flying up as she stands over the subway grate. He later photographed the filming of The Misfits, with a number of glamorous portraits of Monroe and the rest of the cast, for a feature called “MM’s Men” in American Weekly.

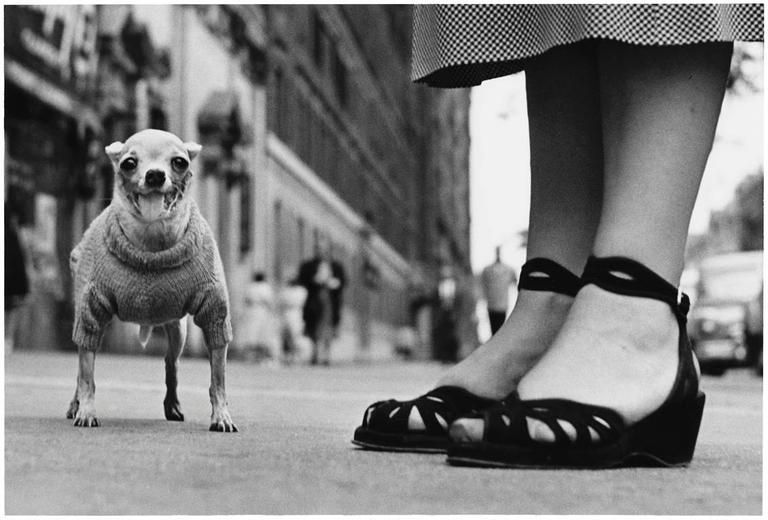

Some critics have observed that it took another Magnum photographer Inge Morath to reveal the discord and dissipation on the set. For all his gifts, Erwitt has never been one to explore emotional conflict, nor sexual desire. Those critics find it revealing that his most poignant photos are of dogs and children. After such a difficult childhood, and a history of four marriages, can this be a surprise?

Yet the Santa Monica photography dealer Peter Fetterman feels such criticism misses the point of Erwitt’s work entirely. ““Because his photographs often have a sense of humor, their greatness is sometimes discounted and that’s nonsense. One of my favorite photographs of his is of the little boy looking out of the back window of the L train. You can read so many emotions into the journey he’s on. The true test of any great photograph is if you keep learning from it, and that’s true of all of Erwitt’s work. The images sustain you.”