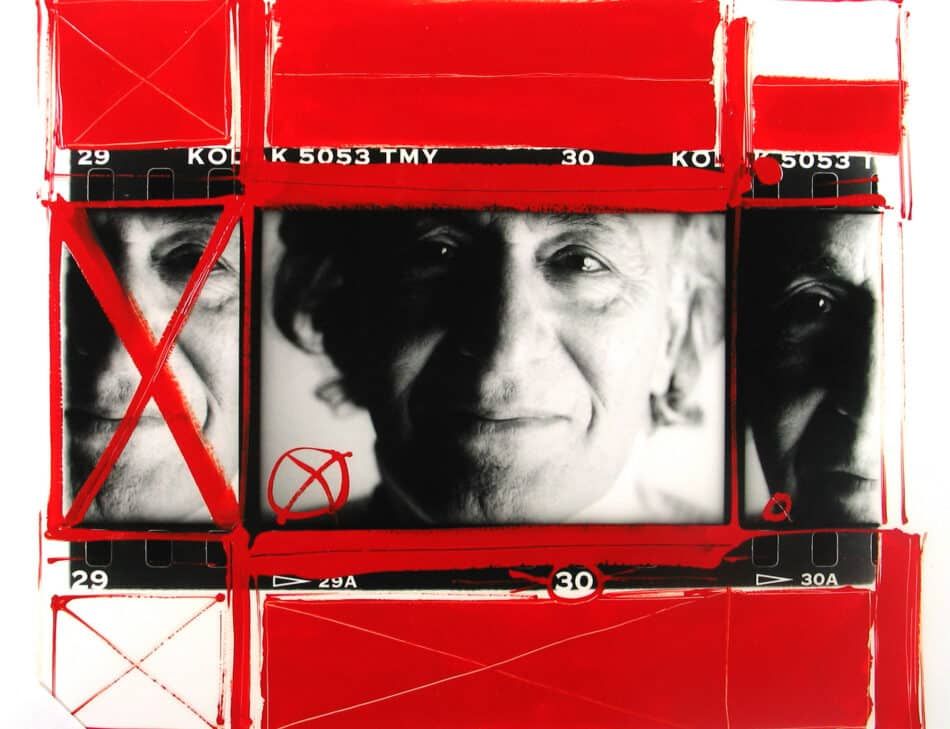

Marc Jacobs and Klein, Paris, 2005, by William Klein. © William Klein, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

It’s hard to think of a modern image maker as prolific and innovative as William Klein, whose remarkable and varied career spanned seven-plus decades. The American photographer, who died on Saturday at age 96, continually channeled the zeitgeist through his oeuvre, imbuing his images with startling honesty and empathy, as well as his own particular brand of abstraction. The portraits, scenes and scenarios resemble windows into a world where reality has begun to warp, sometimes dreamily, other times more emphatically, so that snapshot moments are strangely portentous or full of possibility.

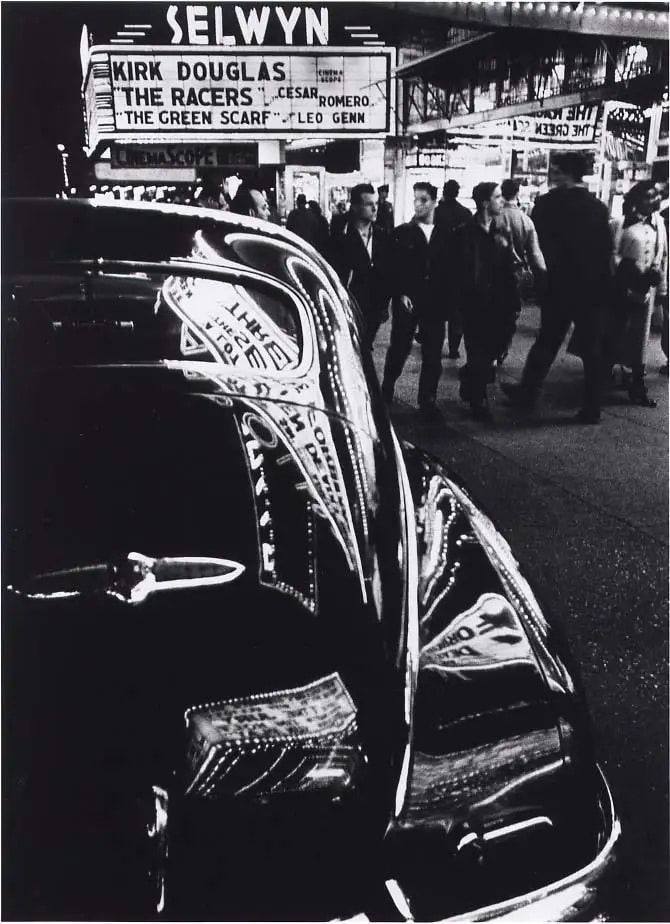

Klein was best known for his early fashion shots and arresting street photography, capturing, with candor and humanity, life in cities around the world, including Rome, Moscow, Tokyo and Paris. His gritty and grainy images of 1950s New York are widely considered his most powerful, documenting the underbelly of a growing metropolis, with his focus set on the energy and multidimensional nature of postwar culture. In his 1955 image Selwyn Theatre, 42nd Street, New York, for example, he contrasted the gleaming silhouette of a car with the faded-out forms of a group of young men about town, creating strong graphic patterns that suggest a sense of abandon and opportunity.

Klein’s aesthetic, however, is not easy to summarize, since he demonstrated an eager embrace of experimentation through the decades. Early street shots are often out of focus and taken at unexpected angles, while his 1960s fashion shots and celebrity portraits for Vogue’s American, French and British editions are sleek and subtly surrealist, pioneering a new style that put the spotlight on the beauty of the composition rather than the allure of the clothes, as seen in Smoke and Veil (1956) and his 1961 portrait of Anouk Aimée for Paris Vogue.

In addition to photography, Klein explored painting, filmmaking, graphic design and publishing, adopting a polymathic attitude to the arts. His ability to excel in multiple disciplines was often overlooked, according to British curator and author David Campany, who knew the artist for almost two decades. “Klein is often celebrated for a single body of work, be it film or fashion photography or street shots,” Campany says. “But this narrows the understanding of his talent, which was completely unfettered. Klein never hid. He was always present in the situation and at the heart of the matter.”

The retrospective “William Klein: YES; Photographs, Paintings, Films, 1948–2013,” curated by Campany at New York’s International Center of Photography (ICP), seeks to correct these restricted perspectives with more than 300 works that celebrate Klein’s artistic vision in all its guises. The point is driven home by the word yes in the title, encapsulating the artist’s expansive approach to creative expression.

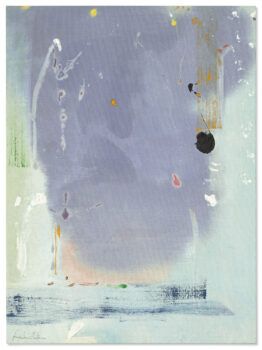

Klein began his career as a painter under the tutelage of French abstractionist Fernand Léger, having moved to Paris in 1948. The experience opened his mind to the possibilities of manipulated form, specifically the illusionary effects achieved through the playful arrangement of light and shadow.

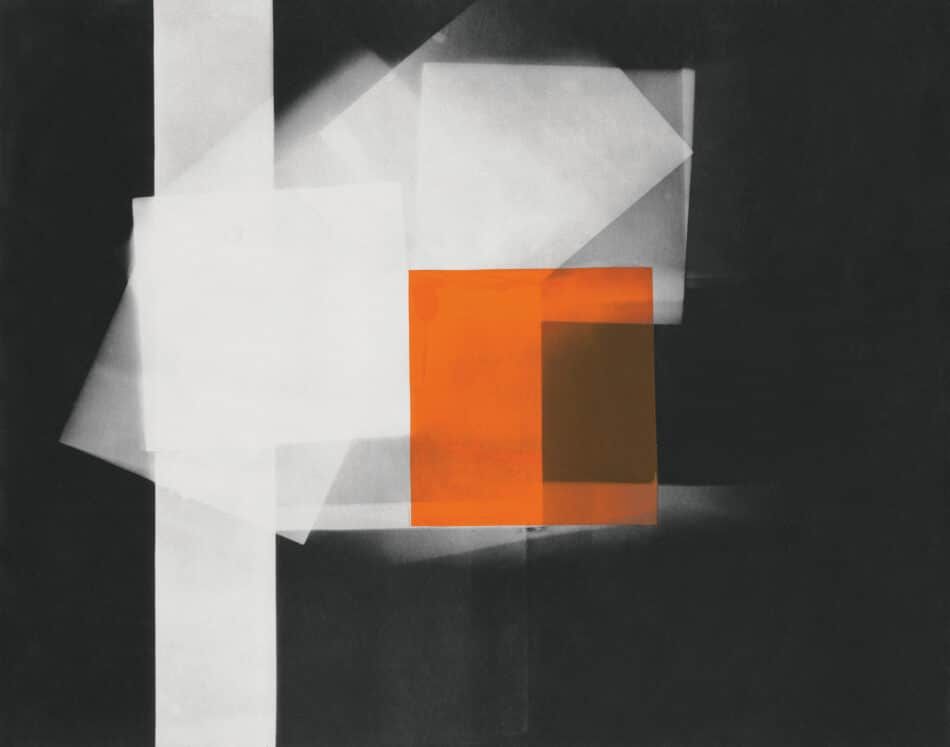

A commission from 1952 was instrumental in his side step into photography. Having created a painted room divider for an architect, Klein took photographs of the rotating piece. His delight in the fragmented shapes created by the movement prompted him to make thousands of abstract photograms by applying shifting geometrical forms on photographic paper during long exposures.

These compositions, some of which are in the ICP show (on view through September 15), illustrate Klein’s flair for a graphic order as well as his talent for making carefully calculated moments appear ethereal and incidental.

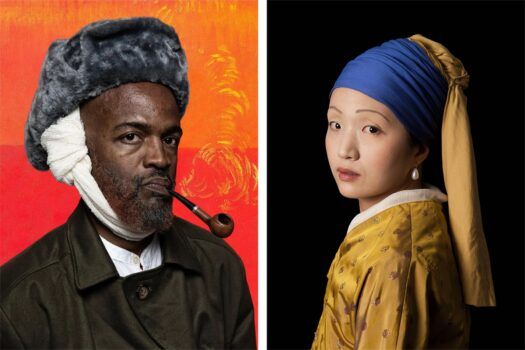

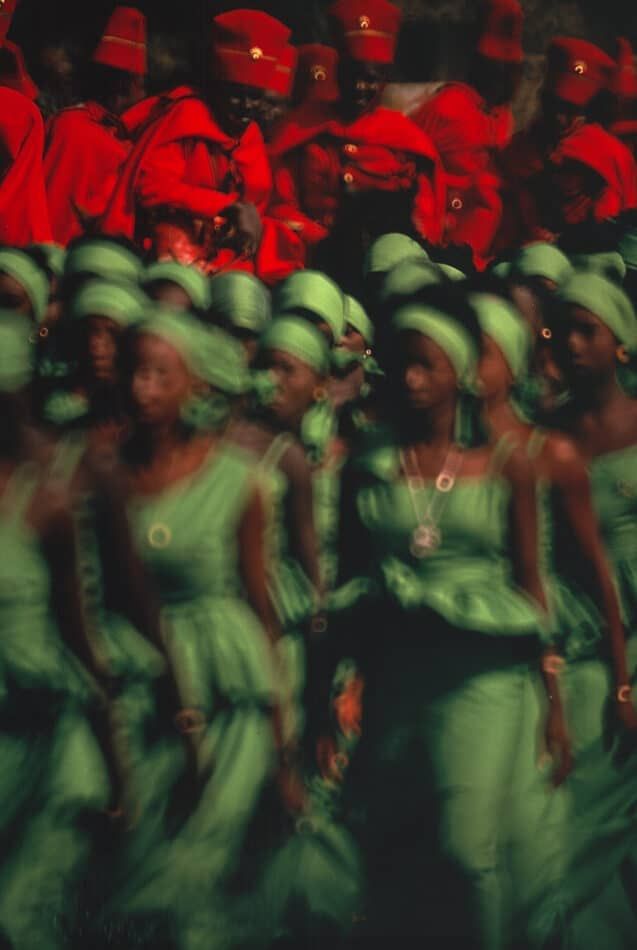

Indeed, the unorthodox mixture of disorder and imperfection, along with beauty and energy, remained a constant in his work, as evidenced by such unconventionally arresting images as Candy Store, Amsterdam Avenue, New York (1955), Independence Day Parade, Dakar (1963) and Black Venus West Indian Day Parade, Brooklyn, New York (2013). “How you can continue to be that sharp over such a long period totally baffles me,” remarks Campany. “There was a certain kind of restlessness to him that never faded.”

Among Klein’s most famous celluloid achievements is his 1964 documentary Cassius the Great, dedicated to a young Muhammad Ali in the run up to his fight with Sonny Liston. “The film was shown throughout Africa, celebrating not just the chutzpah of a superstar sportsman but the birth of an icon who stood for a new kind of Black consciousness,” says Campany.

In fact, many of Klein’s photographs and films have a strong sociopolitical dimension, although they were not intended as acts of propaganda. Instead, they raised awareness about conditions of flux, antagonism, hope and change, especially among African American and minority communities as they navigated times of change. This is exemplified by vibrant shots like Easter Sunday, Harlem High Hat, New York and Moves and Pepsi, Harlem, both featured in the self-designed and self-published seminal tome New York: 1954.55.

In 1969, Klein released his film The Pan-African Festival of Algiers, chronicling the event when leaders of African nations united in their denunciation of imperialism and colonialism. Thanks to this film, Klein was introduced to Black Panther activist Eldridge Cleaver, who was exiled in Algiers. The encounter inspired the artist to make a documentary about the charismatic and controversial revolutionary and donate 50 percent of the proceeds to the Black Panthers.

“Klein was always at his creative best when in unfamiliar territory and slightly out of his depth” says Campany. “He was a total problem solver, so he always figured out the perfect visual language to convey the environment he found himself in, whether the message was rooted in art, politics or culture. Although he spent many years in Paris, he was a Jewish guy from New York who always wanted to know about people, their lives and their connections.”

The curator notes that the retrospective, the largest of its kind ever to be dedicated to the artist in the United States, held particular significance for Klein. “His grandparents were Jewish-Hungarian émigrés who settled in the Lower East Side and actually had a business on Delancey Street, very close to ICP,” he explains.

“The 40,000-square-foot location is the perfect place to accommodate the huge scope of his work and the size of his prints, with many walls showing five or six images at once,” Campany continues. “And there are no ‘relics’ in vitrines. The pages of seminal books like New York are shown via projections, because Klein’s work needs to live and breathe. The joy for me is that I can actually see people’s shoulders lift when they enter the exhibition. There are so many ‘wow’ moments.”

Editor’s note: The article was updated on September 13, 2022, to reflect William Klein’s passing.