This week, dozens of photography dealers have set up booths on New York’s Pier 94 to display their best works in the AIPAD Photography Show, one of the biggest fairs of its kind. The exhibitors hail from cities the world over — including Beijing, São Paulo, Belgrade and Laredo, Texas — bringing pieces that are historical, vintage and freshly printed. Here, we highlight seven standout pieces in this year’s show (on through April 7).

Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future I (LN0309), 2018, by Reuben Wu, at photo-eye Gallery

Reuben Wu’s pictures of rockscapes are so unusual one could take them for photo-illustrations. The lighting is too perfect, the colors too strange to be pure photography. And in the case of the piece titled Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future I (LN0309), 2018 (above), what’s with that glowing ring in the sky, floating over a desert peak like a halo?

“Traveling to remote locations, Wu frames his subject matter, often expansive geographic formations, against the inky night sky — but his light source is neither natural nor traditional studio lighting,” says photo-eye Gallery director Anne Kelly. So, how does Wu achieve his surreal effects? Drones.

These aerial helpers are equipped with spotlights to strategically illuminate the rocky surfaces, making them appear to glow from within. Wu’s photos are contemporary in their use of technology and primordial in their subject matter (no signs of human life here). The combination produces eerie images that are evocative of an alien planet.

Namhla II, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2016, by Zanele Muholi, at Yancey Richardson Gallery

South African artist and activist Zanele Muholi aims to disrupt the way black women are depicted in photography. For the series “Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail the Dark Lioness),” Muholi dressed up in regal-looking garb made from such everyday objects as clothespins, coat hangers and bicycle tires. The self-portraits tackle issues of gender and race to counteract the problematic portrayal of African women in documentary photography.

“In Namhla II, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Muholi is adorned with respirator masks, cables and bijoux jewelry in an effort to reference ethnographic depictions of African tribal queens,” says Sarah Durning Cope, sales director of Yancey Richardson Gallery. “Muholi is reclaiming this iconography by subverting the traditional context for this type of imagery and creating it on their own terms.”

The artist’s costume plays with exaggerated proportions, while the long exposure time used to make the gelatin silver print deepens the contrast between dark and light. Amping up the intensity, Muholi stares directly into the camera as if to confront the viewer’s gaze.

Camden, NJ, 2011, by Ben Marcin, at PDNB Gallery

In his series “Last House Standing,” Ben Marcin documents century-old two- and three-story row houses sitting alone on desolate urban blocks of Baltimore, Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey. These survivors once stood shoulder to shoulder with adjacent homes, but today they look skinny and out of context, surrounded by vacant lots of patchy grass.

Many of the buildings are burned out or sealed shut; others appear still occupied and decently maintained. Camden, NJ, 2011 (above), captures twin houses spared the wrecking ball, at least for now. “One by one, the buildings are torn down,” says Missy Finger, co-owner of PDNB Gallery. “Each has its own character and history but now shows decay and seems forlorn.” The boarded-up windows make it clear that no one’s home and that, like their former neighbors, these brick structures may soon be replaced by empty space.

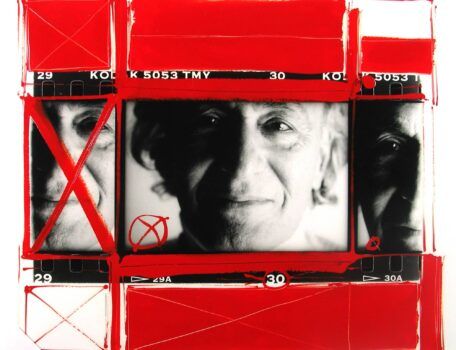

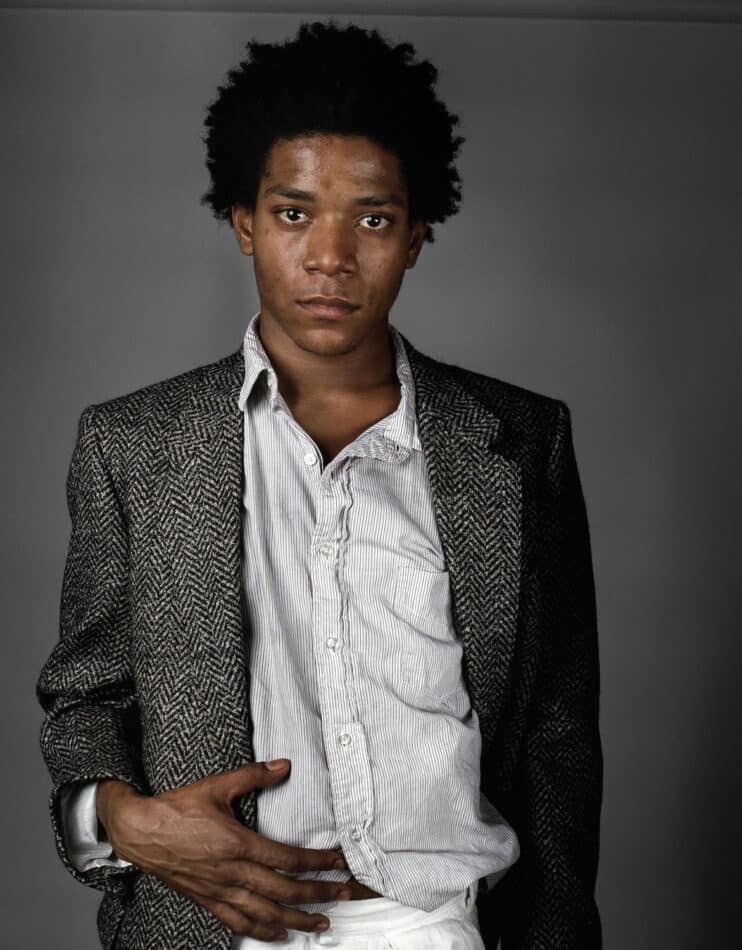

Basquiat a Portrait V, 1984, by Richard Corman, at Peter Fetterman Gallery

In Richard Corman’s 1984 series of portraits for L’Uomo Vogue, we see Jean-Michel Basquiat in his prime, dressed to the nines in a herringbone wool jacket and white linen pants. He’s stylish, confident and insecure, in the way only someone who leaped from homelessness and graffiti writing to art-world fame in his 20s can be. “Corman’s intimate portraits of Basquiat portray the young artist during one of the most pivotal moments of his career,” gallerist Peter Fetterman says.

Although the shoot took place in his bustling, paint-splattered, smoke-filled studio on Manhattan’s Great Jones Street, Corman decided to photograph Basquiat in front of a sheet of gray paper, to put the attention on the man himself.

Because we reside in the 21st century, we have information from the future that loads the portrait with a sense of solemnity. Namely, we know that Basquiat will die of a heroin overdose a few years after posing for this picture. And so, we look for clues: Do his glossy eyes look depressed? Is that the blotchy skin of a junkie? But if we forget about all that for a minute, we can imagine how good it must have felt to be in Basquiat’s borrowed designer shoes at that very moment.

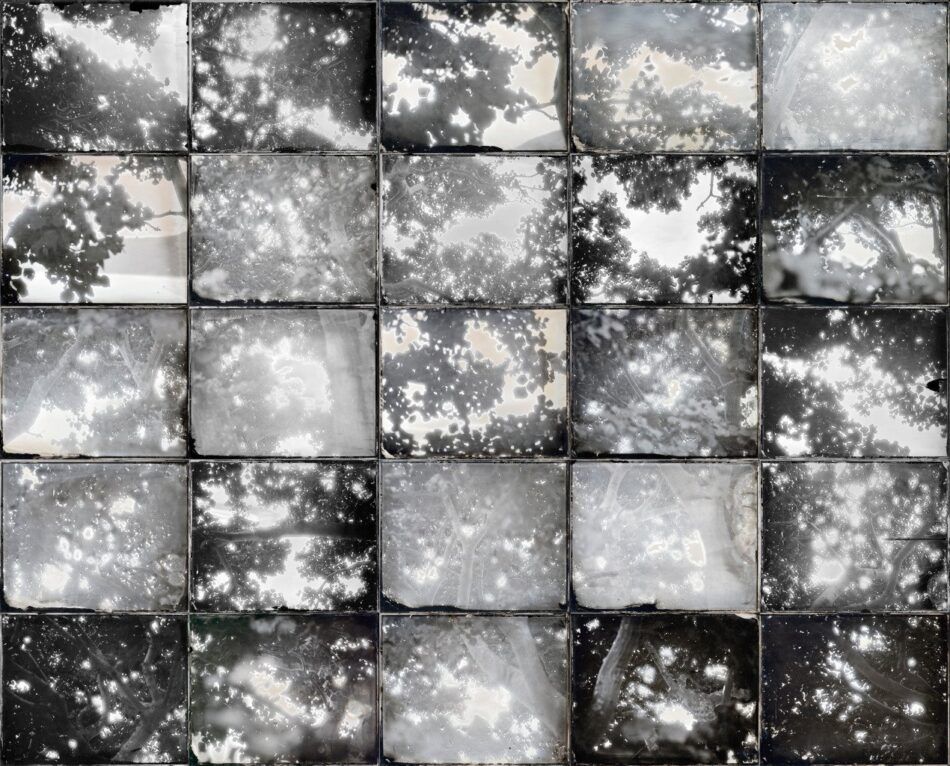

Shodon, 2002, by Ichigo Sugawara, at Sous Les Etoiles Gallery

In 1986, Japanese photographer Ichigo Sugawara was in Paris, looking up at the sky, when he was struck by a profound idea: “Not only does sunlight bring us light, but it also carries a great warmth,” he later reminisced. Ever since then, Sugawara has aimed to reflect that sense of radiant heat in his photography.

“Shodon, 2002, is a wet collodion composed of twenty-five glass plates. In this piece, Sugawara wanted to capture not only the light through the leaves of trees but also the warmth,” notes Corinne Tapia, director of Sous Les Etoiles Gallery. The bright flares and irregularities created by the wet-collodion process are what make Shodon feel so warm. The sunlight seems to pour between the leaves to hit your cheeks just right.

Young Man, Y’s for Living, Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1988, by Kurt Markus, at Staley-Wise Gallery

Portraits don’t get much more poetically minimalist than this. We are presented with only the side of a face, a head and shoulders draped in a white robe and a plain backdrop. Without any context, this guy could be a druid, a shaman, a Saharan nomad. In fact, Young Man, Y’s for Living, Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1988, originated as a piece of fashion advertising — it’s a true work of art nonetheless.

Staley-Wise Gallery’s Etheleen Staley explains: “In 1988, the Japanese designer Yohji Yamamoto chose Kurt Markus to photograph any subject of his choice for a brochure of photographs for a subsidiary of Yamamoto’s label Y’s for Living. Markus chose to go to Vicksburg, Mississippi, where he contacted the Jackson Street Missionary Baptist Church and photographed several of the churchgoers in garments from the Y’s for Living collection.

“Church members were photographed in T-shirts, pajamas, bathrobes, etcetera,” the dealer continues. “Staley-Wise subsequently had an exhibition of these photographs and Markus donated his proceeds from the show to establish an art scholarship for young members of the church.”

Root and Frost, 1958, by Minor White, at Laurence Miller Gallery

Sixty years ago, you could have purchased Minor White’s Root and Frost for a mere $50. This particular print, as its back reveals, was part of the former Art Lending Service at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which encouraged members to buy or even rent reproductions of works from the museum’s collection (not unlike what the MoMA Design Store does today).

The photo presents us with a wine bottle with a root sticking out of the top like a cloud of smoke, all silhouetted before a spotlighted window pane covered in crystalline frost formations. It’s a strikingly abstract composition but still too representational for White.

“The presence of the bottle indicates that this is a very early print, as Minor eventually decided that the inclusion of the bottle diminished the ephemeral nature of the picture,” says gallerist Laurence Miller. “Thus, future prints and book illustrations have the bottle cropped out.”