It is, quite literally, “the thing to wear.” With a history that spans more than 1,000 years, the kimono has amply earned this simple yet emphatic translation. The uncomplicated T-shape design, cut from a single bolt of (usually glorious) cloth, was protected by law in 1950, deemed bunkazai hogo ho, “cultural property,” something that provides insight into Japan’s art, history and way of life.

But the garment’s allure knows no boundaries, national or otherwise. “You can’t love fashion and textiles without loving kimonos,” says Katy Rodriguez, founder of the luxury vintage design boutique Resurrection. Adds Bridgette Morphew, owner of the eponymous Morphew, “It’s unisex and appeals to all sizes and ages.”

It’s the kimono’s balance between two competing identities — cultural icon and fashionable attire — that underlies its attraction today.

But here’s the thing: More likely than not, we’ve got the kimono all wrong. We gaze at elegant images of geisha from our limited Western perspective and think with reverence, “How timeless! How unchanging!” Not true, insist the curators of two exhibitions: “Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk,” at London’s Victoria and Albert through October 25; and “Kimono Couture: The Beauty of Chiso,” at the Worcester Art Museum, in Massachusetts, launching online November 28.

The kimono, says the Worcester’s Vivian Li, is “a living art practice inseparable from contemporary life.” This sentiment is seconded by Anna Jackson at the V&A, whose show dismantles timeworn clichés to demonstrate “that kimonos have been at the heart of a thriving fashion culture in Japan since the mid-17th century.”

So, what do you need to know? Let’s begin.

HISTORY OF THE KIMONO

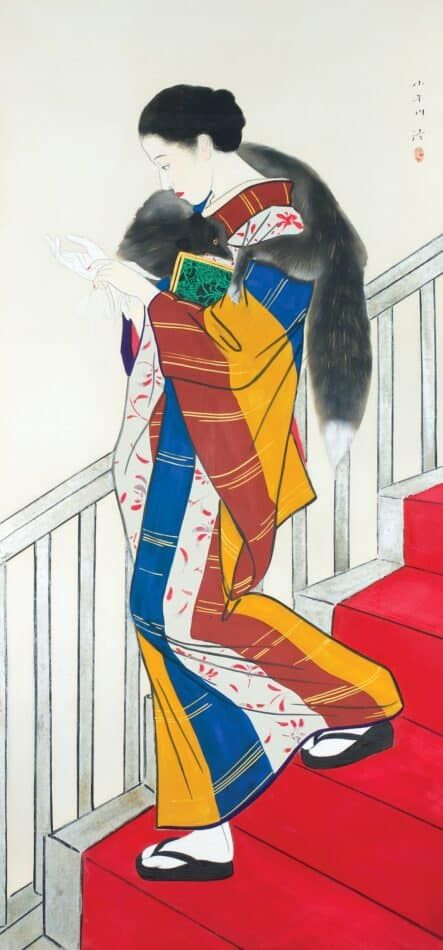

A precursor to the kimono, the kosode, first appeared in the Heian period (794–1192). It was the Edo period (1603–1868), however, that saw the “most dynamic” development of the garment, according to Jackson.

“It was a time when merchant classes demanded ever-changing styles through which to express their growing affluence, confidence and taste,” she explains, “when kimono designers and retailers worked with publishers of books and prints to exploit commercial opportunities and when desire for the latest clothes was fed by a celebrity culture of famous actors and courtesans.”

Summing it up, Jackson describes it as “a fashion world not dissimilar to our own,” which fostered an “enormous variety” of new styles and artistic techniques.

In 1853, United States warships arrived off the coast of Japan; soon afterward, the country was forced to open its ports to foreign trade. This led to a sartorial revolution, as men (especially those in the political class, who were eager to appear modern) exchanged their national dress (wafuku) — including the kimono worn by both sexes — for Western-style clothing (yofuku).

Most women, however, continued to dress traditionally. The result was a feminization of the kimono. A 1925 survey found that 99 percent of the women wore wafuku, versus only 33 percent of men.

Kimonos were banned in 1940, so the materials used to make them could be used instead in the war effort. In the difficult years following the surrender, the garments were prohibitively expensive. It was during this time that the kimono began to be worn primarily for special occasions.

THE CRAFT OF KIMONO

Making a kimono is the Eastern equivalent of French couture.

The process “involves over 600 highly trained, inventive and innovative craftsmen,” says curator Christine Starkman, who worked with the 450-year-old kimono maker Chiso on a garment commissioned for the Worcester museum show. It begins with considering dying techniques and consulting pattern books and Japanese paintings developed and collected over 15 generations.

“The fabric is sent to the dyers and draftsman, who draw the design on the kimono by hand,” Starkman explains. “The kimono is sent to different craftsmen, depending on the technique (tie-dyeing and other dyeing methods, embroidery and gold application) and in order of application.” The garment is lined and possibly paired with an overcoat (uchikake) for formal events.

THE KIMONO AND WESTERN FASHION

Duro Olowu belted wrap coat, Autumn/Winter 2015 (© Duro Olowu)

Say you were having your portrait painted in 1660s England and wanted to appear worldly, sophisticated, even a little intellectual. One garment would do the trick: the robe-like Indian gown, inspired, despite its name, by the kimono.

The kimono’s influence is evident throughout the history of fashion. You can see it in Liberty & Co.’s tea gowns and in Paul Poiret’s radical corset-free designs of the early 20th century. It’s visible in Madeleine Vionnet’s innovative cutting and, later, in the visionary creations of Christian Dior, John Galliano, Jean Paul Gaultier, Comme des Garçons, Thom Browne and Duro Olowu.

Vintage kimonos continue to have a following, says Morphew, noting that the best sellers are those made from lighter fabrics, which are easier to wear. Meanwhile, the style inspires fresh takes. “It’s the most universal shape,” says Rodriguez, of Resurrection. “Designers really love taking this classic design and adding their own twist.”