Two names are synonymous with the best of Surrealism: Salvador Dalí and René Magritte. Even if you do not know the Belgian painter and author Magritte’s name quite as instantly as Dalí’s, you’ll likely recognize his ionic, ambiguous 1928 work The Treachery of Images.

The Surrealist style is identified in academic and popular culture with that ever-reproduced piece, which shows a wooden pipe rendered in the direct style of sign painting with the words ceci n’est pas une pipe (this is not a pipe) painted rather crudely beneath it.

Although Magritte is best known as one of Surrealism’s most talented artists, his famous 1943 painting, The Fifth Season, can be interpreted as a formal break from the movement. That piece represents a stark departure from his usual works, portraying two nondescript men donning Magritte’s signature bowler hats and carrying framed canvases beneath their arms. The expressionistic marks a clear shift by Magritte away from Surrealism in the face of the bleakness of World War II.

The paintings that followed The Fifth Season were done during and after the war, when many hitherto ironic artists — Pablo Picasso, Hannah Höch, Max Beckmann — began to rethink art’s philosophical role in asking those so-called big existential questions. Magritte even looked back to turn-of-the-century art movements in his compositions.

Earlier this year, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art put together an exhibition and sumptuous catalogue “René Magritte: The Fifth Season,” which casts new light on the depth, meaning and collector cache of late-career Magritte works.

The Study sat down with Ruth Berson, deputy museum director of curatorial affairs at SFMOMA, who eloquently informed us why Magritte was much more than a Surrealist.

One of the premises of the exhibition was that Magritte formed a distinct vision as an artist after breaking with the movement of Surrealism.

While Magritte engaged consistently with the ideas of Surrealism, he eventually cut ties with the Surrealist circle of Paris. Our exhibition looked at the span of the 1940s to the end of his life, a period after the Surrealist group had largely disbanded.

In fact, Magritte resisted the label of “Surrealist” throughout his career. He once said in an interview that he supposed he could be called a Surrealist because one had to use one word or another, but one should really say that he was involved with realism.

Though this is the case, he is still strongly touted as a major example of Surrealist concepts.

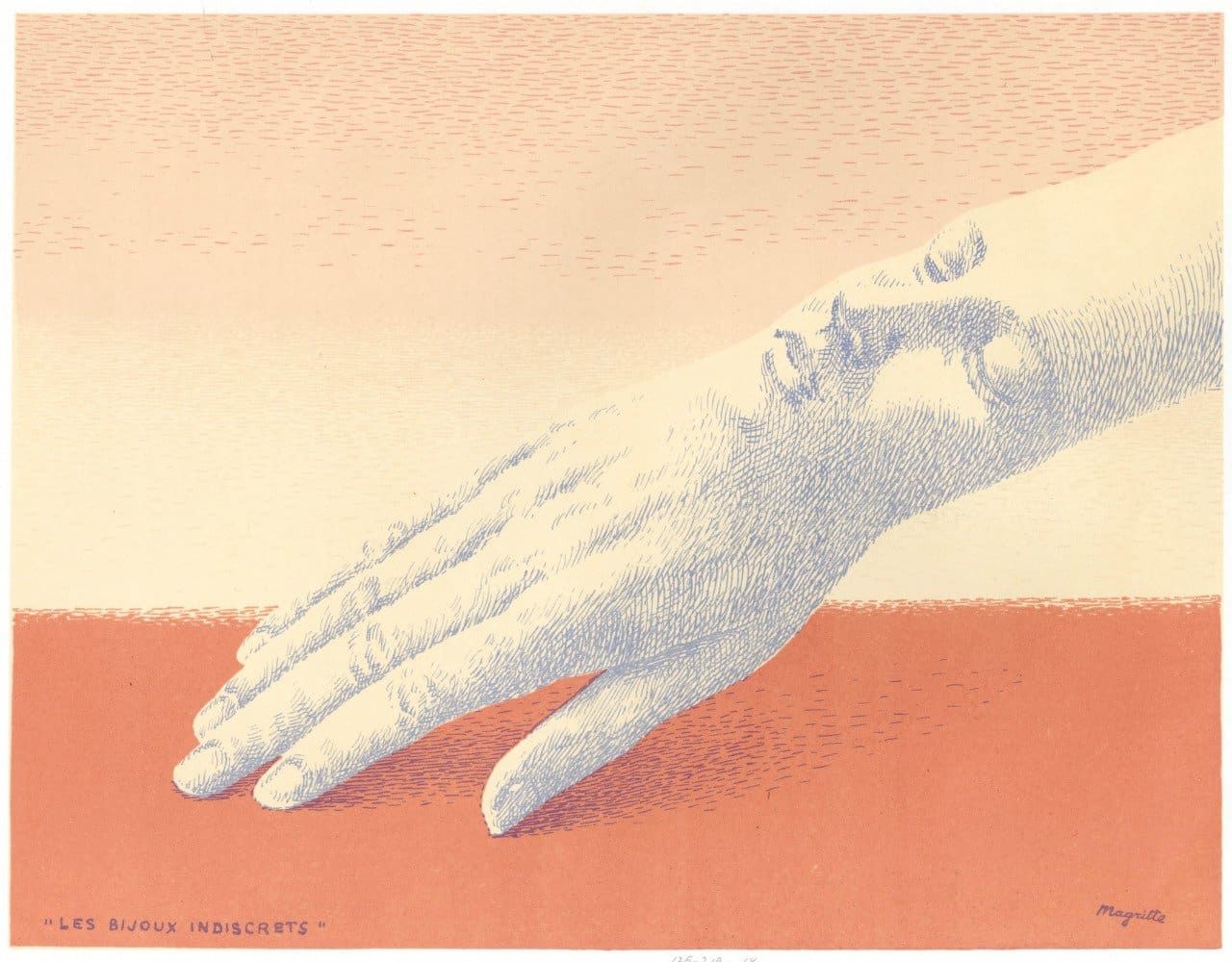

Magritte always considered his painting a philosophical undertaking, awakening viewers to the wonder of everyday experiences through extraordinary compositions. During his time working with the Paris Surrealists, he collaborated on a number of texts and completed many iconic paintings, including The Treachery of Images.

But the focus of this show is work done after his break with Surrealism.

“René Magritte: The Fifth Season” begins with two revolutions in Magritte’s painting style. He invented the first one during the war years, in 1943, with a body of work known as “Sunlit Surrealism.”

These paintings are shocking, fantastic, and unsettling in the ways that Surrealism can be, but they were painted in a wildly different style than Magritte had used before, employing a pastiche of Impressionism, with thick, hazy atmospheres and bright, saccharine tones.

The next stylistic shift that Magritte took was in 1947 and ’48, when he completed a series of works during what is known as his “Vache” period. This French word means “cow” in most contexts, but there’s another sense of vache, too: to behave badly.

These paintings were purposefully harsh, combining aggressive, flat colors and the aesthetics of popular cartoons with loose brushwork parodying Fauvism and Expressionism.

These changes of style and choices sound extremely thoughtful — frankly, the exact opposite of Surrealism’s undirected creativity. Can you comment on that?

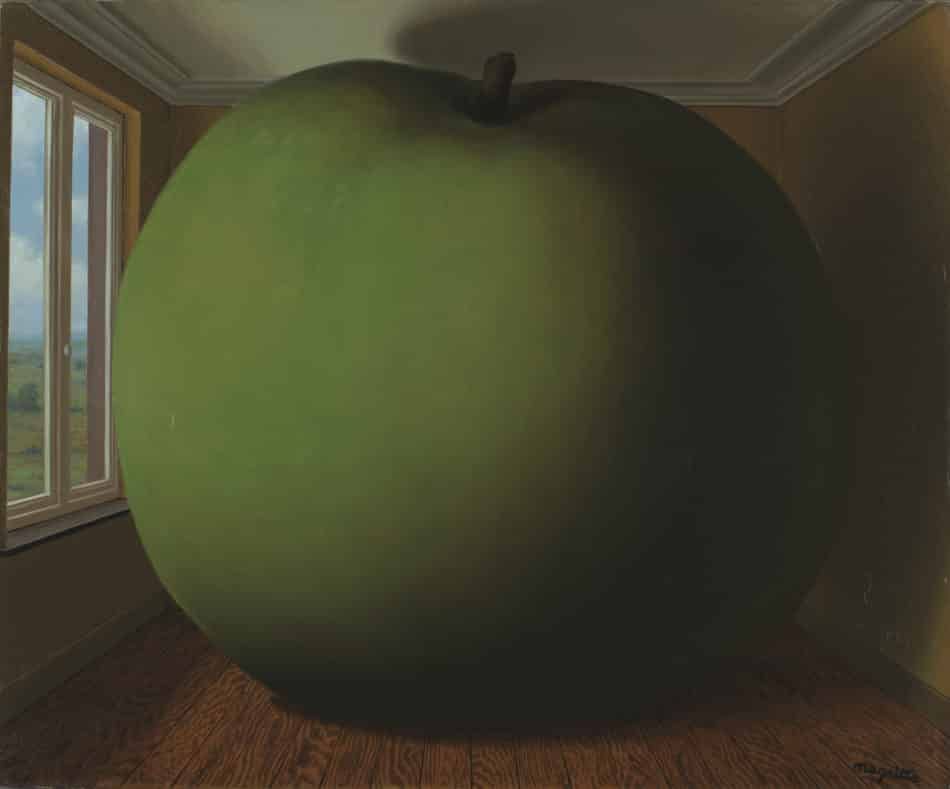

After these departures from his signature style, Magritte returned to his compact, highly representational approach, but these two bodies of work are signals that Magritte deliberately tried to make paintings that provoked unsettling responses and rode a line of ambiguity.

After seeing how an artist can so drastically and dramatically shift styles, viewers can better understand how Magritte’s representational work is also a choice — there’s no such thing as a “neutral” painting.

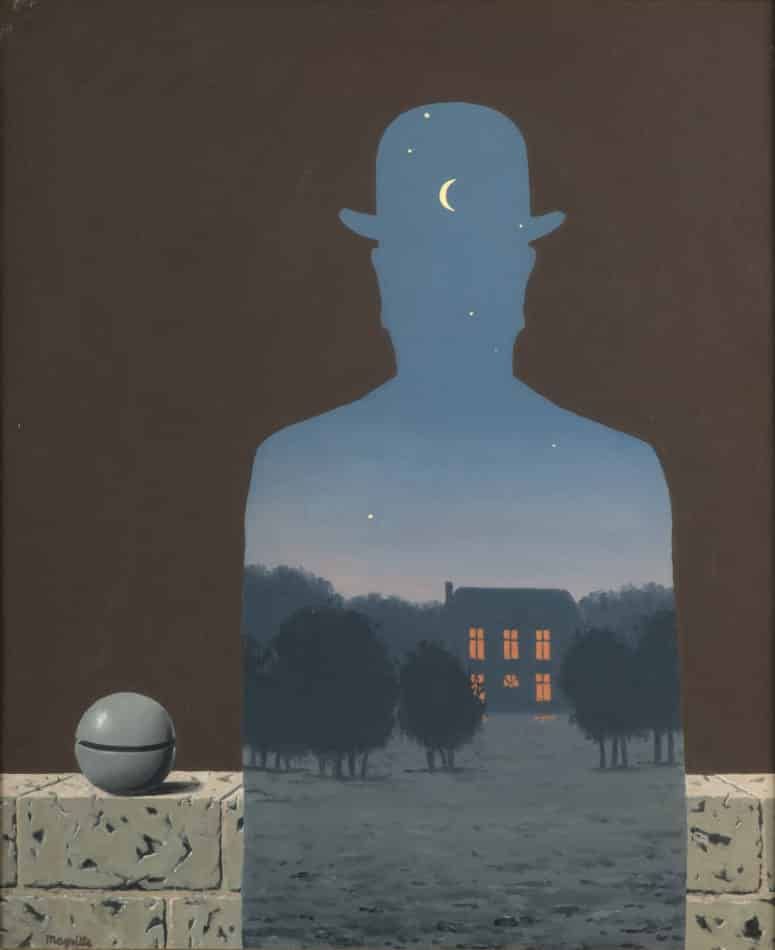

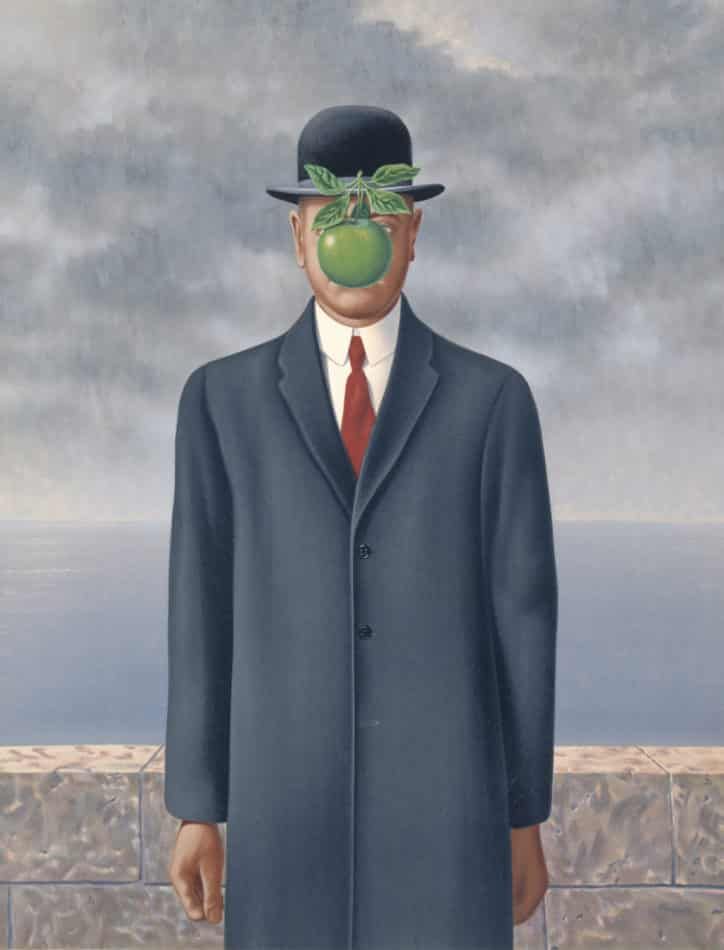

Magritte is well known for his depiction of a man in a clad in bowler hat. Much is made of his use of that symbol, that it was used to refer to Everyman or was biographic trope because he referred in his work to himself.

The bowler hat — known in French as a chapeau melon — first appeared in Magritte’s work in the 1920s, inspired we now know in part by the dress of characters from detective movies he enjoyed. It was only in the 1950s that the bowler-hatted man became synonymous with his oeuvre and in the 1960s, with the artist himself.