Angelo Donghia and Diana Ross leaving a Bette Midler show in 1978. Photo courtesy of Donghia

Dapper and debonair, the son of tailor from a steel town in western Pennsylvania, Angelo Donghia (1935–85) possessed an easy confidence about his prodigious talents that enabled him to blaze new trails as both a designer and businessman. As he told an interviewer in 1977, “just because I said in 1959, ‘I’m going to be an interior designer,’ doesn’t mean that I should die being an interior designer. I’d like to write a book. I’d like to do a movie. I’d like to do everything.”

Eight years, later, when AIDS cut his life tragically short at age 50, entrepreneur had already built a design, furnishings and licensing empire with gross revenues exceeding $60 million. He had showrooms in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Washington, D.C., Miami and Troy, Michigan, along with design offices in New York and Palm Beach. And he was clearly just getting started.

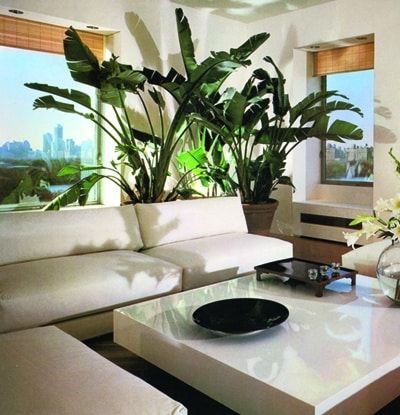

Ricky and Ralph Lauren’s Donghia-designed Manhattan apartment. Photo courtesy of Donghia

Perhaps, it’s because his life came to such an abrupt end that his interior designs are no longer as well known as his namesake furniture company, which continues to flourish today. Also, Donghia never had one look. While he brought his own innate taste and vision to every project, he always took into account the needs and taste of his clients and the times.

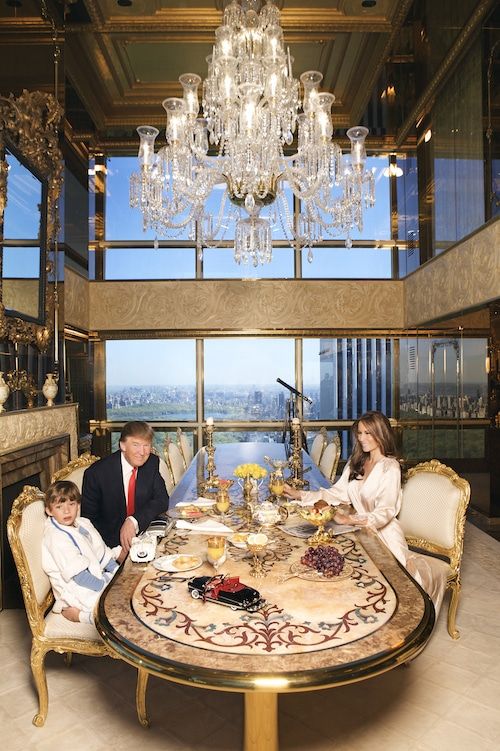

Still, he will likely be best known for the way in ’70s he fused glam maximalism with cool minimalism: rooms with foil ceilings, lacquered walls, bare windows and bleached floors, furnished with groupings of plump frameless chairs and sofas, suited in gray flannel or white duck or creamy satin, mixed with a few antique showstoppers and big tropical plants. You might call the look Disco Deco, an updated interpretation of the sets of the stylish Hollywood movies of the ’30s that Donghia loved so well as a boy. Whatever you call it, the glitterati of that era — Woody Allen, Burt Bacharach, Steve Martin, Liza Minnelli, Diana Ross, Barbara Walters and yes, even Donald Trump — sought out Donghia to get it.

In the 1980s, Donghia designed the famously opulent New York penthouse of Donald Trump, shown here in 2010 with his wife, Melania, and their son, Barron. Photo by Regine Mahaux/Getty Images

Many interior designers make their careers by socializing upwards through their clients. Not Angelo Donghia. He didn’t like to mix business with friendship, which is why in 1979, he almost didn’t design the Upper East Side duplex of his chums Ricky and Ralph Lauren, a home that they have barely altered to this day. In order to convince him, the Laurens had to insist there was no one else who could interpret how they wanted to live as well as he could. Yet Ralph Lauren later admitted that he and his wife were a bit stunned when Donghia stripped the apartment of its beautiful prewar moldings, leaving the walls starkly white and unadorned. But that was the point. Donghia had transformed the space into “an uptown loft,” the perfect timeless retreat for a fashion titan immersed each workday in colors, patterns and fashion trends.

Of course, as a charming talent on the rise, Donghia couldn’t help but form friendships with a number of his clients. Another close buddy was Halston. In 1967, as a backdrop for Halston’s spare, graphic fashions, Donghia designed a showroom on Madison Avenue that the New York Times described as being “as multipatterned as a souk.” As part of the Halston crowd, he often squired Minelli and Diana Ross to Studio 54. And later, he sold his Key West Victorian octagonal retreat, all bamboo furniture and zebra rugs, to Calvin Klein.

Nevertheless, his focus was not so much on courting celebrities as corporate clients. One of the most important was Pepisco, for whom he designed the corporate interiors in Purchase, New York. He also designed the Intercontinental Hotel in New Orleans and the Omni International in Miami, plus he helped convert the luxury liner SS France into the contemporary S.S. Norway cruise ship. And he was keen to seek out commercial opportunities wherever he could. He was the first American decorator to put his name on a mass-produced line of sheets for JP Stevens, and that Windowpane pattern became an industry bestseller. Before long, he had also put his name on a mid-priced collection of stylish gray flannel furniture, along with glass and dinnerware.

In 1966, Donghia designed the Opera Club at the new Metropolitan Opera House in New York’s Lincoln Center. Photo courtesy of Donghia

After graduating from Parsons School of Design in 1959, Donghia joined the design firm of Yale R. Burge, with a starting salary of $300 a month. Burge quickly recognized his protégé’s immense talent and initiative and, in 1963, appointed him a vice president of the firm. Not long after, he received the commission to design the Opera Club, at the new Metropolitan Opera House in New York’s Lincoln Center. The sleek, luxe interior, with its silver-foil ceiling, blue-glass chandeliers and black-upholstery thrilled operagoers when the house opened in 1966, with many spectators reputedly hiring Donghia to design their homes on the spot. A turning point in his career, the Opera Club remained one of his favorite projects.

Soon after, Burge made him a partner of the firm, changing its name to Burge-Donghia. When Yale Burge died, prematurely at 55, in 1972, Donghia renamed the firm Donghia Associates. He had now way of knowing he had only 13 more years himself to live, but he certainly made the most of them.