Elaborate flowers are synonymous with Capodimonte porcelain. Why? Was it because King Charles VII of Naples, who founded the manufactory in 1743, was allergic to the blossoms growing in his garden and wanted a hypoallergenic version?

Or did the perfect blossoms result from royal competition? After all, by the 18th century, China’s long-held monopoly on (ahem) china had finally been broken. And several leading courts of Europe had begun developing their own porcelain.

Madame de Pompadour, chief mistress of Louis XV of France, is said to have commissioned Sèvres to create an entire indoor garden of porcelain botanicals. Surely, Charles would not want to be outdone by the French.

If success is measured by lasting name recognition, Capodimonte would seem to be in the same league as such makers as Meissen, Sèvres and Wedgwood. The Real Fabbrica (“royal factory”) di Capodimonte, however, hasn’t produced porcelain since the early 19th century, when Charles’s son Ferdinand sold it. Although secondary manufacturers have built upon the aesthetic and kept the name alive, some connoisseurs of the royal product feel these pieces should be labeled “in the style of” Capodimonte.

“The real deal,” says David Sterner, of David Sterner Antiques, in Philadelphia, “the fantastic stuff that’s over-the-top beautiful, is nearly nonexistent on the market. A lot of it is in museums or private collections.”

That’s because the timeline of royal Capodimonte porcelain is decidedly brief. From beginning to end, its manufacture lasted approximately 75 years.

The Story of Capodimonte

Charles VII began experimenting with porcelain around 1738, the year he married Maria Amalia of Saxony. No coincidence there. His new bride was the granddaughter of Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and founder of Meissen, the first European hard-paste porcelain manufactory. Her dowry included 17 Meissen table services.

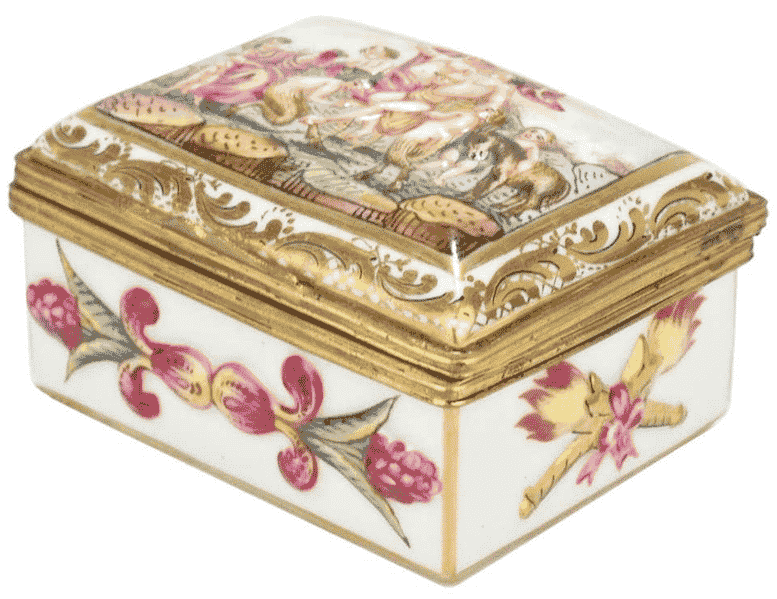

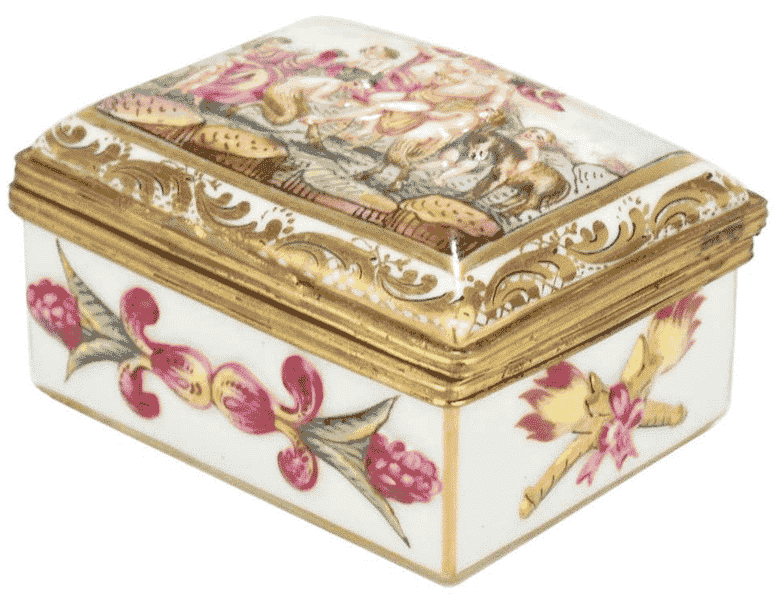

Struck by porcelain fever, Charles built a dedicated facility on top of a hill (capo di monte) overlooking Naples. He financed expeditions to search for the right clay. He hired chemists and artisans to experiment. His earliest successes were small white snuffboxes and vases, although efforts soon progressed to full sets of tableware, decorative objects and stylized figurines of peasants and theatrical personalities.

In 1759, Charles succeeded to the throne of Spain. He moved the manufactory with him — including 40 workers and 4 tons of clay — and continued operations in Madrid. Twelve years later, his son Ferdinand IV, who inherited the throne of Naples, built a new factory there that became known for distinctly rococo designs.

The Napoleonic wars interrupted production, and around 1807, oversight of the royal factories was transferred to a franchisee named Giovanni Poulard-Prad.

Assessing the Value

Beginning in the mid-18th century, porcelain made by Charles’s factory was stamped with a fleur-de-lis, usually in underglaze blue. Pieces from Ferdinand’s were stamped with a Neapolitan N topped by a crown. When secondary manufacturers began production, they retained this mark, in multiple variations. The value of these later 19th- and 20th-century pieces is determined by the quality, not the mark.

“Form matters,” says Sterner. “It’s the quality of the cast and the decoration that influence value.” Look for attention to detail in the painting, he adds, such as edges that are “crisp and well defined.”

Capodimonte is an acquired taste. “You either like it, or you think it’s ugly,” says Frank Bloemberg, of Flowermountain, in Antwerp, who admits the more lavish designs can come off as “kitch.” Still, he says, “Italian ceramics are often beautiful, and so different from those of other countries.”

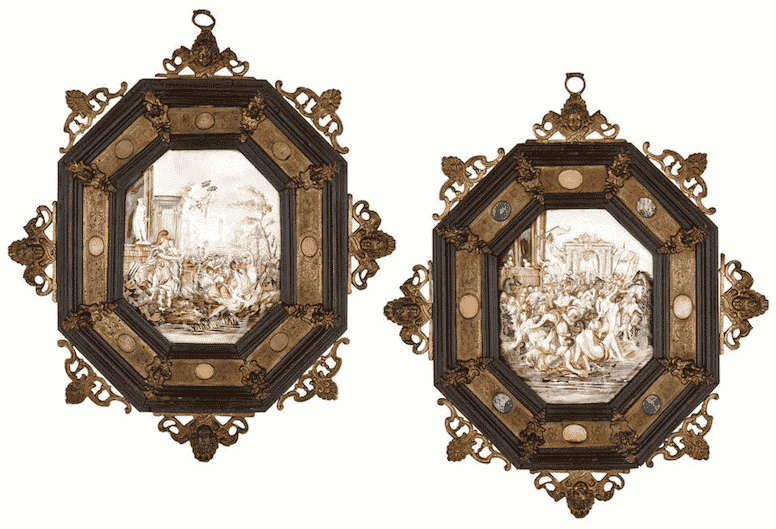

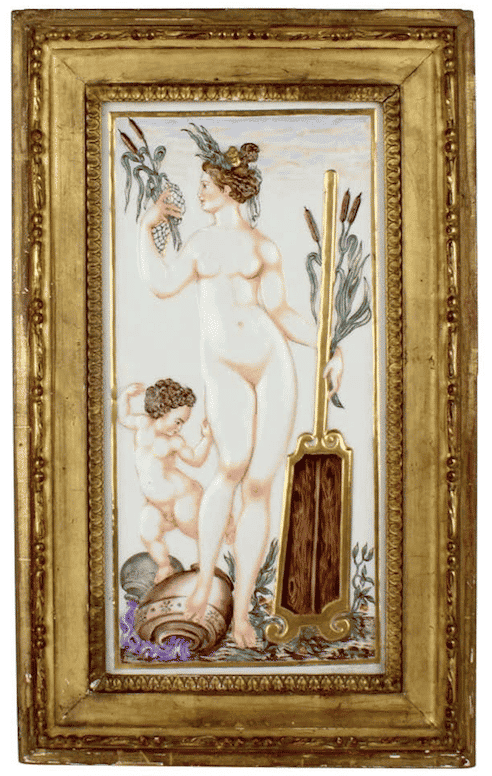

“I have been fascinated with porcelain for the longest time,” says David Biscaye, of New York City architecture and design house Biscaye Frères. “I use it in every one of my projects. But to me, modern porcelain is dead looking. The old stuff just has character.”

Biscaye’s taste in Capodimonte is very specific: He collects only white porcelain from the early factories. He believes it has the most range. “White can be placed in historical or modern settings. And in a modern setting, it looks spectacular.”