Merriam-Webster defines a pattern as “a repeated form or design,” but that only tells part of the story. It’s not just repetition that makes patterns eye-catching; it’s the context in which they are used. Take Robert Kime, one of Britain’s most revered interior decorators, who layers pattern upon pattern to create the cozy, lived-in spaces for which he is famous. It’s a clever technique that has the result of making his rooms feel as if they were slowly created over time. Then there’s whimsical New York interior designer Fawn Galli, whose penchant for using one knockout pattern in a room — say, Cole & Son’s Lily wallpaper in a pale pink 60s-style bedroom — seems to reflect its provenance while subverting it at the same time.

It’s helpful to know a pattern’s backstory, because the goal isn’t always to make it look pretty. Sometimes you want to know its origins so you can play off them, making a statement uniquely your own. With that in mind, we’ve compiled a guide to eight of the world’s most popular patterns.

The Southern picnic staple has surprising origins in southeast Asia, and no, it’s name doesn’t translate to check or checked in English. Gingham derives from the Maylayan word genggang, or “striped,” which is actually how the pattern looked — that is, until factories in Manchester, England, and the southern U.S. co-opted it. Pressed by hard times to produce simple and inexpensive designs, they began manufacturing gingham in the 18th century, foregoing the stripes in favor of the checked pattern popular in the U.K. By the mid- to late-19th century the pattern could be spotted on tablecloths, aprons and other pragmatic workwear associated with the American frontier.

The ancestor of a pattern known as “Opus Spicatum,” or “spiked work,” herringbone got its name for resembling the skeleton of a herring fish. Its oldest examples can be traced to Rome, which may explain why it appears in menswear so much. But long before its foray into fashion, the pattern of interwoven chevrons was used in ancient Rome’s road paving systems. (Apparently alternating the direction of the bricks helped roads withstand more traffic.) The construction technique soon became a motif in architecture — think Filippo Brunelleschi’s grand Duomo cathedral in Florence — and flooring. Today the alternating twill weave remains one of the most sophisticated patterns, right up there with houndstooth and tartan.

Design legend Dorothy Draper was photographed wearing a houndstooth-patterned suit and matching hat in the 1930s, and top fashion houses regularly used the motif in their collections. But long before Christian Dior set his eyes on the print in the ‘60s, houndstooth was worn as an outer garment by shepherds. Its earliest appearance dates back to Scotland in the 1800s, where over time it evolved into a staple pattern in wool suiting and outerwear. The versatile pattern, which is characterized by protruding jagged teeth, is the result of highly technical weaving and not a pattern transferred onto fabric.

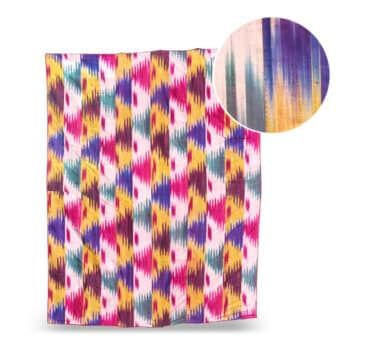

Ikat:

The current craze for ikat prints seemed to be a contemporary preference, but in reality, Western cultures have been embracing the pattern for centuries. The technique has roots throughout Asia and Africa, and is said to date from the 10th century. But while its provenance is fuzzy, ikat’s appearance is anything but: No two motifs are ever alike, and they can never be duplicated. It takes three steps for ikats to get their watery look. First, warp threads are tied into bundles and dyed, then they’re secured to the loom. As the weft thread is weaved through, the design begins tol emerge. The handcrafted process is what gives ikats their feathery edges.

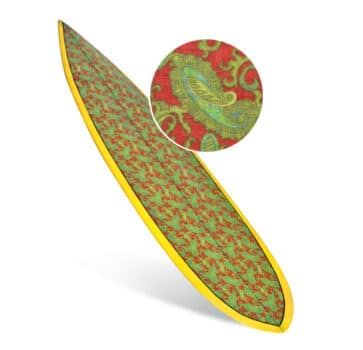

Though it wasn’t born in the town of Paisley, Scotland, the swirling floral pattern was popularized there. More shawls were produced there than anywhere, and Paisley became its generic name as a result. The first shawls were made in Paisley around 1808, and by 1850 there were over 7,000 weavers in town. By the early 1870s, the paisley shawl began to fall out of fashion, largely due to the advent of bustles and the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–1871, which halted exports of shawls from Kashmir. So where did paisley come from? Kashmir, of course, where industrial production of the shawl supposedly started in the 11th century.

If tartans call to mind flame-haired men carrying bagpipes and swords, you’re correct: The origins of the pattern are inextricably tied to Scotland. When the Scoti tribe arrived from Ireland in the fifth century, they didn’t just give the nation its name but an everyday garment that came to symbolize Scotland’s identity. As time passed, the number of stripes on a cloth were used to signify rank while weaves became associated with different clans around the country. In 1746, the British government tried to ban the wearing of tartan but ended up adopting their patterns in an effort to win over rebels. Fast forward to 2009, and the Scottish Parliament established a Register of Tartans, proving the pattern was here to stay.

Long associated with country châteaus and stiff-backed settees, toile de jouy is truly a product of its time. It all started when German-born Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf moved to Paris in 1758, when he quickly formed a partnership with a former employer and set up a cotton factory in the town of Jouy-en-Josas. With the advent of copper plate technology in France, which not only allowed for large, repeating patterns but finer detail and shadows, Oberkampf began commissioning artists to produce series of bucolic scenes. Soon cotton apparel was being used to depict the highlights of the time, from the first flight in a hot air balloon to France’s fixation with India. In all, more than 30,000 designs were made at the Jouy-en-Josas factory, and the phrase toile de jouy became a label for a style of print.

One of the oldest dyeing techniques in Japan, shibori designs vary from highly symmetrical patterns to streaky splashes of color. It all depends on the type of technique used: Kanoko, Miura, Kumo, Nui, Arash and Itajime are just a few. There are infinite ways to do it — and, therefore, no shortage of patterns to make — but most shibori techniques involve folding, twisting or bunching and binding the cloth, and then dyeing it indigo.

Story by Jill Krasny, a New York City-based writer. View more of Jill’s work here.