When I was a young editorial assistant at Vogue in the early 1980s, I had the extraordinary good fortune to become acquainted with the legendary photographer Horst P. Horst. My boss, Barbara Plumb, was in charge of the magazine’s “Fashions in Living” section, which featured the stylish homes of stylish people. And as Vogue had no greater photographer of style than Horst, he was the lensman with whom she most often worked. In fact, Vogue’s fabled editor Diana Vreeland had expressly revived the section in 1963 as a special project for her great friend and his longtime partner Valentine Lawford, a former British diplomat turned writer, as she felt Horst’s fashion photography had by then become “too fashionable,” and he was “in need of a change.”

Barbara adored Horst, not just for his exceptional talent and suave professionalism, but his entire beguiling being. Back then, he was in his late 70s — he died in 1999 at age 93 — but he was still strikingly handsome and manly, with a quick and sparkling smile. While he spoke English fluently, his deep, gravelly voice had a lilt that evoked Old World cultivation more than Weissenfels, Germany, where he was born and raised as Horst Paul Albert Bohrmann, the second son of a prosperous hardware merchant. That isn’t to say there was pretense to Horst’s articulation, only that he’d been very keen to evolve.

While Horst came to live an impossibly chic life — he counted Coco Chanel, Marlene Dietrich, Jean-Michel Frank and Luchino Visconti among his friends and lovers — it wasn’t a lust for glamour that fueled his determination to leave Weissenfels, as much as a passion for art, especially avant-garde architecture. In fact, you might say that the crux of Horst’s artistic genius was his ability to somehow infuse the Old World into “the new,” producing fashion photography and society and celebrity portraits that were at once bracingly modern and timeless. When Horst died, his friend, the photographer Eric Boman commented to the New York Times: “He really was the twentieth-century.”

After studying with László Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus, Horst moved to Paris in 1930, when he was 24, to serve as an apprentice to Le Corbusier. But within a year of his arrival, he met George Hoyningen-Huene, the trailblazing chief photographer of French Vogue, who became Horst’s lover and mentor and turned his ambitions from architecture to photography. A Baltic baron whose father had been chief equerry to Czar Nicholas II, Huene brought an innate sense of classical refinement as well as a gift for technical invention to his daring black-and-white image-making. While Horst learned as much as he could about the medium from him, he later confessed he couldn’t replicate Huene’s “infallible sense of elegance.” Instead, as he explained in Lawford’s 1984 monograph Horst: His Work and His World, “I had to invent it on my own: more exactly, to learn gradually to recognize elegance in others and to portray it in my photographs.”

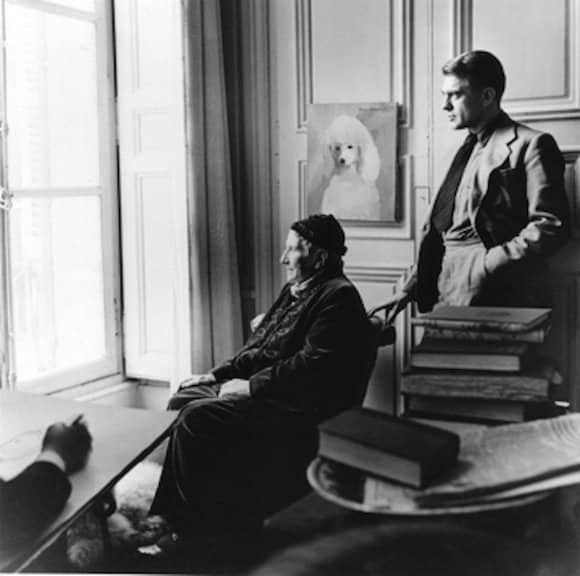

When Huene left Paris in 1935 for New York, Horst replaced him at French Vogue. By now part of the creative coterie that included Gertrude Stein, the artists of the Ballets Russe and the Surrealists along with their moneyed and aristocratic admirers and patrons, Horst found himself aswirl in new approaches to imagery and presentation. This inspiration, along with the fresh ways that fashion, society, and commerce were mixing, enabled him to be boundlessly creative in his work.

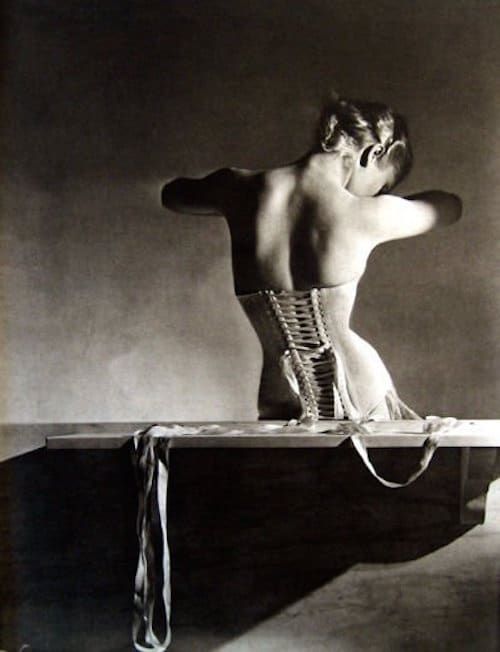

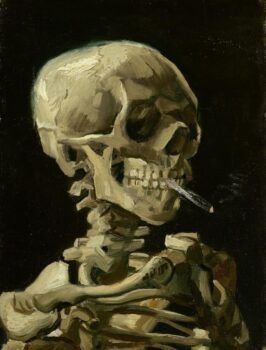

Take his 1939 photograph of a Mainbocher corset. Shot his last night in Paris before World War II, the image remains potent because it is more than a fashion photograph, it is a richly evocative work of art, evincing a theatrical mastery of light, shadow and pose, and a keen knowledge of art history, alluding to Velázquez as well as de Chirico.

“In Europe, the lens is taken as seriously as the palette,” Janet Flanner observed in a 1932 review of Horst’s earliest work. Yet Horst also saw himself as a documentarian of “the spectacle of modernity,” and his melancholy and foreboding over what he then intuited was the ending of an era, pervades the Mainbocher image. The next day he boarded the Normandie for New York, where he’d already begun working for American Vogue. Aware of his vulnerability as a German alien, as well as his indispensability to the magazine, the powers-that-be at Condé Nast were by then in the process of acquiring U.S. citizenship for him. When it did come, in 1943, to distance himself from his roots, and the prominent Nazi Martin Bohrmann, he changed his name to Horst P. Horst.

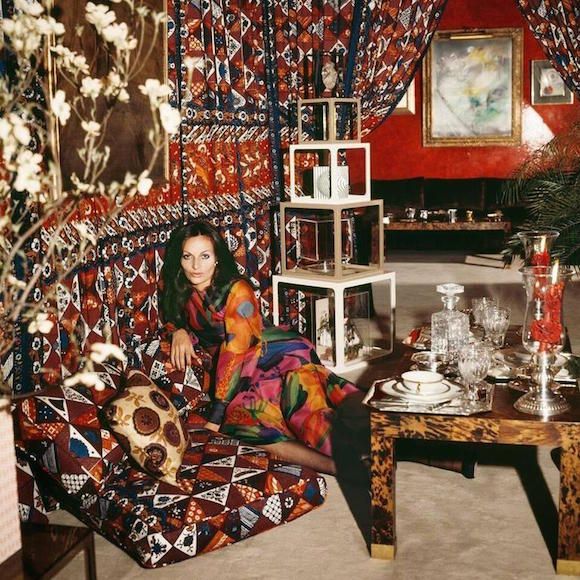

Horst brought the eye of a documentarian to his interiors photography. More precisely, he was like a documentarian on holiday, because once out of the studio, his imagery took on a surprising air of insouciance and intimacy, even though every photo was painstakingly conceived. I remember well that these interiors stories would often take well up to two weeks to produce — impossible to imagine today — as Horst would wander for several days about the house and garden at different hours to determine the most becoming light for every carefully composed shot.

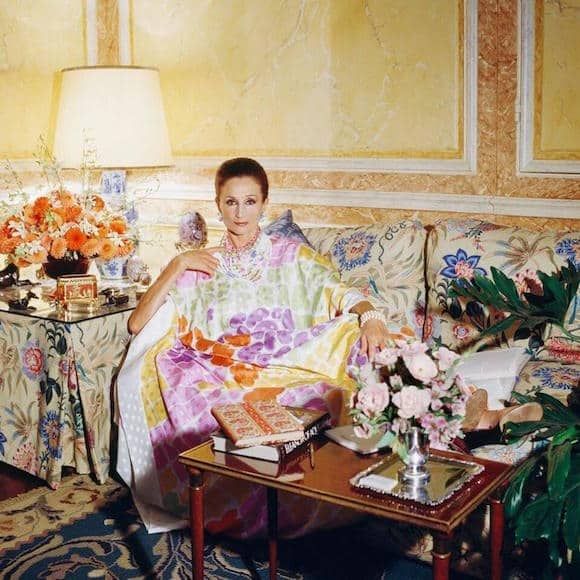

During this research, he also looked for telling domestic details and vignettes that might speak to the personality of the home’s owner. And when shooting a portrait of the subject, he always asked them to pose in their favorite space within the house. Then he would position his camera from across the room looking through a bouquet of flowers or from a corner to give an impromptu look to the image. Possibly the most fabulous and famous of these is his photograph of Pauline de Rothschild opening the secret door to her Paris bedroom, a sylvan fantasia of 18th-century chinoiserie wallpaper, minimally furnished with Louis XVI chairs and a steel and brass four-poster bed of her own design. Seeing just this one image, you can understand why Horst returned four times to photograph the utterly alluring and original interiors of this American-born French baroness.

In one of the most recent monographs about his oeuvre, the encyclopedic Horst: Photographer of Style (V&A Publishing), which accompanied a major 2014 retrospective of his work at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the curator Glenn Adamson observed that Horst was snobbish about the homes he shot, preferring those of storied blue bloods to the merely wealthy. Hamish Bowles in the foreword to Around That Time (Abrams), a gorgeous new book of Horst’s interiors photography, repeats that comment.

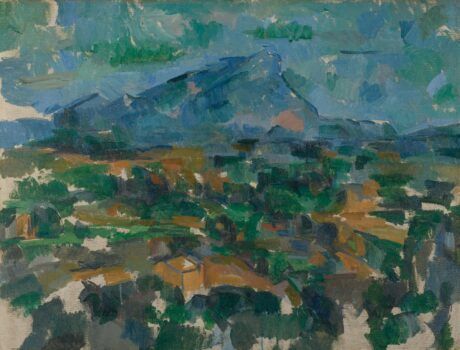

Yet there is no further attribution for that view in either case. My personal encounters with Horst were admittedly limited, although he did take me out for a long lunch once, but I never got a sense that he was a snob. He understood that the kind of lives being lived in the grand houses of the chatelaine of Mouton-Cadet and former Duchess of Marlborough, which were so devoted to a kind of formal beauty, were in their twilight. And as he was an unabashed aesthete, how could he not be captivated by the chance to document the history, the romance, the elegance of these individuals and their homes?

While Horst was certainly aware he was a master of his craft, he never thought about his fashion or interiors photography as art. So when the founders of Staley-Wise, the New York gallery dedicated to fashion photography, sought out Horst to be the subject of their inaugural show, in 1981, he was surprised by the request. “Horst took a lot of convincing,” says Etheleen Staley, “but he was always a risk taker.”

If Staley-Wise is to be thanked for first making Horst’s fashion images accessible to collectors, accolades should now go to Juan Carlos Arcila Duque and his Florida gallery the Art:Design Project, which in collaboration with the Horst estate and Condé Nast, has brought us new limited-edition portfolios of his interior photography. Now, we can all bask in the beauty and elegance of a time now past.