For nearly two decades, Mira Nakashima worked in the shadow of her legendary father, George Nakashima. She never intended to follow in his footsteps, but she was persuaded to join him in his woodworking business after earning a graduate degree in architecture from Tokyo’s Waseda University.

That part-time position turned into a full-time job, and when George Nakashima died, in 1990, Mira was faced with a choice: continue the family legacy or shutter the business. As news of her father’s death spread, clients started canceling orders, fearing that the studio’s innovation would wane without him at the helm.

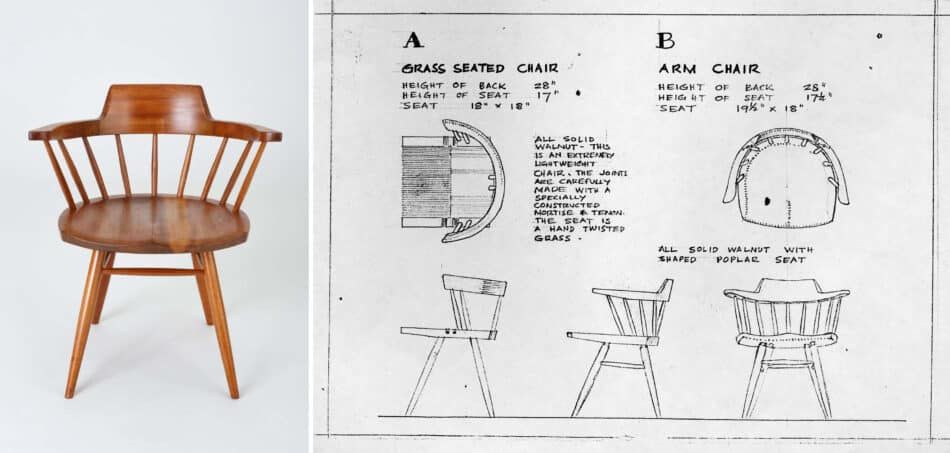

Skeptics proved wrong. Mira Nakashima continued to execute her father’s iconic designs while also creating new ones of her own that take advantage of and highlight the unique characteristics and allure of her, and her father’s, favored material. “Keisho means ‘continuation’ in Japanese,” she tells Introspective. “I am just as interested in traditional lines, classic proportions and fine wood specimens, but I work out my designs differently. The boards tell you what they want to reveal.”

In honor of Women’s History Month, Nakashima recounts how Japanese-American artist and furniture maker Wendy Maruyama has inspired her both through her craft and through how she has met the challenges of creating in the male-dominated environment of woodworking.

Obviously, your father has had a huge influence on your work, but have any female designers particularly inspired you too?

I have been much inspired by my friend Wendy Maruyama, who not only taught woodworking in San Diego for many years but is Japanese-American as well.

What about her work have you found impactful?

She shares a Japanese heritage and sensibility, but with a feisty sense of independence that makes her tackle outrageous projects, making her art and craft a from of highly effective social protest. She is fearlessly outspoken.

How is her influence reflected in your work today or in how you operate as a furniture maker?

Knowing Wendy has made me more independent and outspoken, but she is much more of a hands-on maker of conceptual objects than me. I am more of a designer and supervisor to a shop full of mostly male woodworkers, who take my drawings from raw wood to the reality of furniture.

We have tried our best to be true to the norms and forms my father developed over the years, only occasionally venturing out to develop something new.

How has being a woman in the industry affected your work?

I don’t know. The job just needed to be done, and I was there to do it. I was grateful to be accepted and helped by my Japanese classmates in architecture school, by the woodworkers who had worked with my father there and by the shop of workers I have grown up with.

I think being a woman has made what we do a much more collaborative process than it used to be when my father was in charge, and I hope that will translate into longevity for the business.