Romance is in the air at Waddesdon Manor, in Buckinghamshire, England. And quite literally so. On the sprawling grounds of this majestic French Renaissance–style château — known for its extensive art collection, amassed by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild, who built the house in the 19th century — celebrated Portuguese contemporary artist Joana Vasconcelos has created a soaring 40-foot-tall sculptural ceramic pavilion in the form of a three-tiered wedding cake.

Described by Vasconcelos as “a temple to love” celebrating joy, unity and devotion, the sculpture, in place until the end of October, is fully immersive, allowing visitors to enter its curving platforms and interact with its glossy surface, crafted from more than 25,000 glazed tiles in delicate shades of pink, blue, yellow and green.

“I am inviting people to finish this artwork with me,” explains the artist, who has incorporated a crown of gold “icing” peaks on her faience fantasy, as well as the sound of trickling water and special lighting effects. “As people climb all the way around, they become the two figures on the top of the cake.”

Vasconcelos’s fairy-tale structure, built in the tradition of a Victorian folly, is also an expression of place and provenance. The artist articulates her cultural memory through the language of materiality, drawing on the tradition of Portuguese azulejo (tile work), which can be traced back to the 13th century.

“Growing up in Portugal, I have always been surrounded by tiles and ceramics. They are all over the place, and they are an integral part of our culture,” explains the artist, who recently created a giant textile installation for Dior’s Autumn/Winter 2023 show in Paris. Indeed, Vasconcelos’s work, whether fired in ceramic or crocheted in lace, is always flamboyant and colorful, with a touch of the baroque, evoking a joie de vivre that is transportive and deeply rooted in the artisanal history of her native country.

In the case of the Wedding Cake at Waddesdon, the tiles harness the allegorical significance of azulejos, which have been used for centuries to decorate everything from churches and monasteries to train stations and residential houses with scenes depicting historic, religious, agricultural or mythological narratives.

“For years now, I’ve been working with the Viúva Lamego factory [founded in 1849, in Lisbon], which produces the most beautiful handmade tiles,” says the artist. “For the Wedding Cake, I also decided to use ceramic figures that they had stopped producing, such as a mermaid panel and some fishes traditionally used to help drain the water from the rain, and representations of Saint Anthony, the patron saint of marriages in Portugal. Our relationship with tiles and ceramics is very emotional, so they were the perfect medium for installation.”

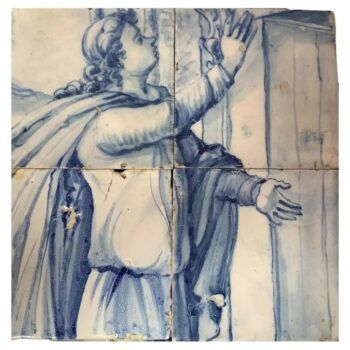

In places like Porto and Lisbon, you can immediately sense this compelling heritage, thanks to an abundance of lavishly ornamented facades and interiors. Streets are colored with blue-and-white azulejo tiles inspired by the Delftware used by Flemish artisans who settled there in the 16th century. Tiles with elaborate geometric patterns have a much longer history, connected to the Islamic motifs of the Moors who ruled Portugal for more than 500 years starting in the early 8th century. In fact, the word azulejo is derived from az-zulayj, meaning “polished stone” in Arabic.

Given their functional purpose and susceptibility to damage, well-preserved antique azulejo panels are extremely rare and are considered highly collectible pieces of art, often used as centerpieces in modern houses. “As a Portuguese citizen, I know what it is like to have these pieces at home and admire their beauty and splendor,” says Jose Afonso Amoros Campos Ferreira, partner in Florin Antiques, in Madrid, which specializes in European antiques and artworks from the 17th to the mid-20th centuries.

In the boutique’s inventory are a variety of perfectly restored 18th-century blue-and-white panels, including a 30-tile mosaic depicting a pair of plump cherubs with hunting dogs framed by an opulent burst of Rococo swirls. Another piece, comprising 108 tiles, portrays a rustic scene populated by figures like a shepherd, a troubadour and a maid with two children. The focal point of the composition is an arched pavilion in the foreground, which, like Vasconcelos’s Wedding Cake at Waddesdon Manor, brings architectural extravagance to a pastoral idyll.

“Buying a panel of vintage Portuguese tiles is like buying a part of Portuguese history,” says Ferreira, whose clients include major collectors in Brazil and the United States. Such works are in high demand, he notes, because of their unique position as investment pieces, straddling the divide between home decor and fine art objects and thus combining functionality and beauty.

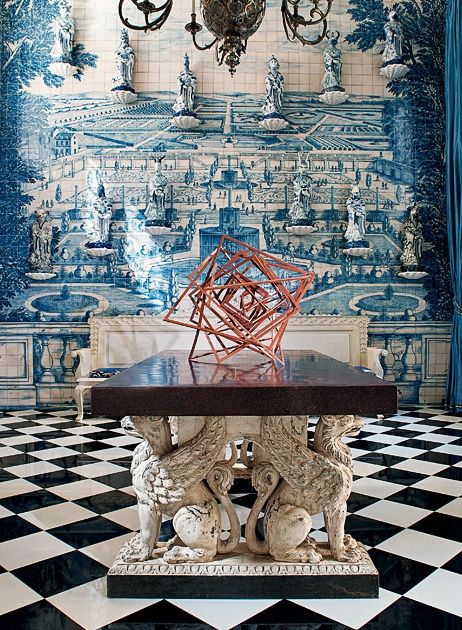

Tiles can also create a sense of depth in a room, altering perspectives and inviting the gaze toward new visual gateways. In a light-filled hallway of a palatial home in Atlanta, for example, designer Brian J. McCarthy introduced an exotic paradise in the form of a large blue-and-white azulejo tableau.

Interior maven Bunny Williams, meanwhile, heightened the romance of a fireplace with a tile surround that sets a homely farmhouse scene. In the salon of Juan Pablo Molyneux’s regal 17th-century Parisian home, azulejos depicting stately gardens and aristocratic residences convey a sense of grandeur and historical pomp, like a floor-to-ceiling storyboard evoking a utopian past.

“I feel that the azulejos are loved not only because they are blue and white, which seem to be universally adored colors, but also because of their ability to change the architecture of the structure’s surface they are applied to,” says renowned Rome-born, Chicago-based interior designer Alessandra Branca.

Aware of the scarcity and high value of vintage panels, Branca has created hand-painted wallcoverings that mimic their designs for a de Gournay collection aptly named Porto. The “tiles” of the trompe l’oeil papers appear glazed and are separated by matte-painted “grout” lines, producing a 3D effect on wall surfaces.

“I have been visiting Porto since I was a young girl, and I am still so enamored by these tiles,” she says. “My favorites, however, are those that feature the suggested architecture of painterly balustrades and overdoors. These wonderful elements can do to an interior what tiles can achieve on the outside. In this way, the plainest box is totally transformed. The azulejos can make spaces sing.”

This is true of both modern and historic examples, whether the tiles are used to conjure a storybook past or a confection celebrating the union of a married couple.