November 28, 2016Two new shows at New York’s Museum of Modern Art show off the institution’s substantial design chops. “How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior” (above) includes furniture, room installations and models — like a 1949 maquette of the Los Angeles home of Charles and Ray Eames, whose storage unit can be seen behind — that highlight the best decor from the 1920s through the ’50s (Photo by Martin Seck, © 2016 The Museum of Modern Art). “Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter” examines the plight of the world’s 65 million displaced persons through design and artworks, including 2016’s Woven Chronicle (top) by Reena Saini Kallat. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar, © 2016 The Museum of Modern Art

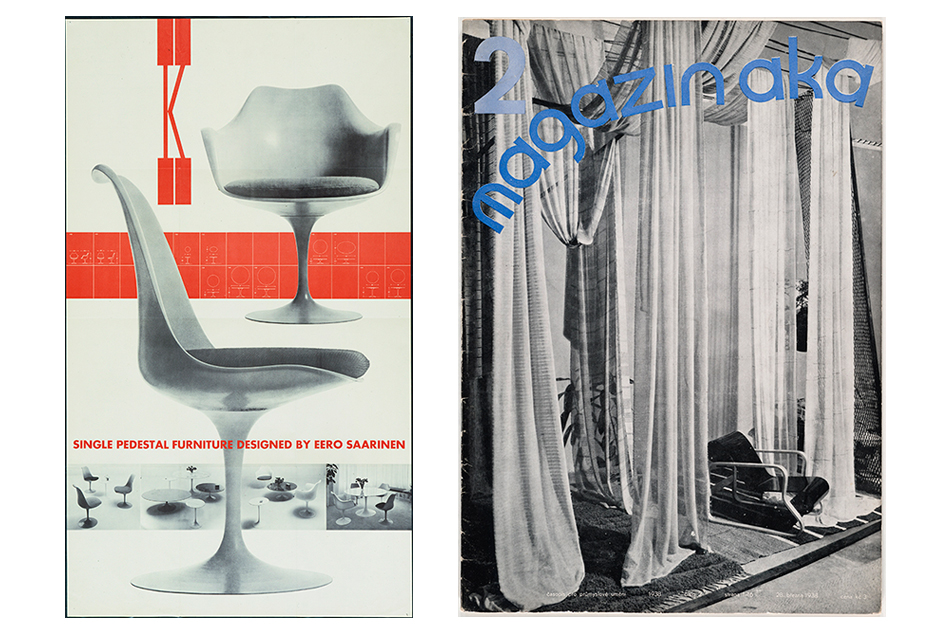

It’s great to see model rooms at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Some of MoMA’s greatest architecture and design shows of the past 85 years have included complete rooms or even complete houses, demonstrating ways of living with an immediacy that no photo or rendering can match. “How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior,” a retrospective of work from the 1920s through the ’50s, is full of furniture groupings that you’ll wish you could try out at home, including a particularly inviting set of designs by Frederick Kiesler. The Austrian-born Kiesler is represented by a puzzle-piece cocktail table and a gum-drop-base floor lamp, as well as a jazzy lacquered sideboard that seems almost too exuberant for an exhibition that appears to be devoted to asceticism.

Drawn entirely from the museum’s collection, the show, which is on view through April 23, 2017, opens with the Frankfurt Kitchen, a highly efficient 1920s prototype for German apartments. Designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, it is the earliest work by a female architect in MoMA’s collection. Some of the model rooms are re-creations. These include Lilly Reich and Mies van der Rohe’s Velvet and Silk Café, which they designed for a trade show in 1927; and a bedroom with furniture by Charlotte Perriand and Le Corbusier from the Maison du Brésil, a 1959 dormitory in Paris.

If these “purely modernist” rooms look a bit subdued, it’s because we’re now used to seeing mid-century furniture alongside works from other periods. And with good reason. The answer to the question “How Should We Live?” is: We should live eclectically. And the designers featured here, for the most part, would probably agree. (I’ve been to the Eames house, in L.A., and it’s filled with tchotchkes.)

A strategic partner of the IKEA Foundation and the UN Refugee Agency, Better Shelter creates solutions for housing refugees safely and efficiently. Photo courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York & Gift of Better Shelter

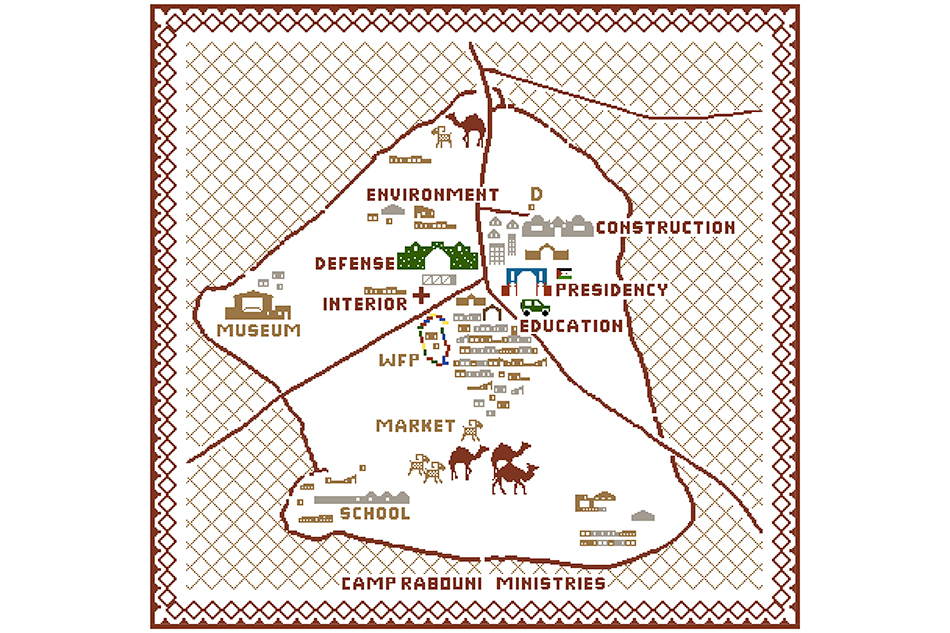

For eclecticism, take the escalators down one level to another MoMA show, “Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter,” up through January 22, 2017. Here, curator Sean Anderson, in his debut exhibition at the museum, has managed to take on a serious topic — the plight of the world’s estimated 65 million displaced persons — in a way that is visually strong and sometimes also beautiful. The largest work in the show is a spectacular world map made by the Indian artist Reena Saini Kallat using colored electrical wire to trace the routes of refugees across the globe. It faces another informative and beautiful item: a rug depicting the Rabouni camp, the administrative seat of the Sahrawi refugees, who were forced to flee Morocco for Algeria in the 1970s. (Manuel Herz, a Basel architect, works with the National Union of Sahrawi Women in creating these rugs, in order to fund building projects in the camps.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the show features dozens of photographs. Artist Tiffany Chung set her images of Syrian devastation into small glowing boxes that resemble votive candles. Anderson even made room for wit, in the form of a welcome mat crafted by Do Ho Suh out of tiny plastic people. Architects Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello, of the Oakland firm Rael San Fratello, are represented by drawings of whimsical border walls, one supporting teeter-totters, another serving as a giant xylophone.

At the center of it all is an actual shelter, a steel-framed, polyolefin-paneled hut designed by the organization Better Shelter in partnership with the IKEA Foundation and the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees. The 190-square-foot building is surprisingly similar to the model rooms in “How Should We Live?” Indeed, the modernists whose work is in that show would no doubt be proud that their pared-down aesthetic and form-follows-function principles, coupled with advances in technology, have made it possible to house refugees efficiently. If only the reasons for doing so weren’t so tragic.