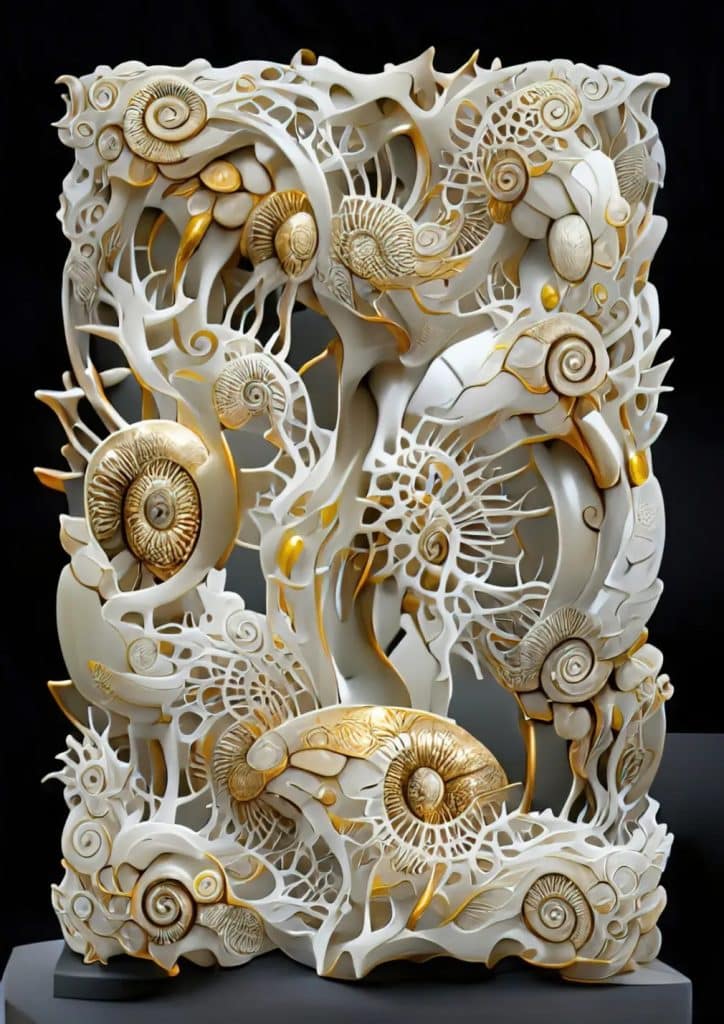

Victoria Fard’s work is alive with detail. The series of three NFTs now available on 1stDibs — AËR, TERRA and ACQUA — are snapshots of imagined worlds, rendered in 3D. All three share a characteristic intricacy, a building up of ornament in a style that could reasonably called baroque. It’s an association she welcomes: “I love the feeling you get in a cathedral, and you’re just like, ‘Wow!’ ” she says, “I’ve always dreamed of making that experience for people.”

Just a brief tour of 1stDibs’ NFT marketplace demonstrates that Fard is far from the only artist using digital tools to reprise the 17th century by way of the 21st. Originally an expression of the power and wealth of the Catholic Church, baroque art took the technical discoveries of the Renaissance and pushed them to radical conclusions, employing not just mythological subjects but dynamic movement and emotion expressed through boiling clouds and tumbling drapery. Its major works required the marshaling of manpower and resources that stretched the budgets of even the wealthiest patrons.

Today, however, baroque’s epic style and scale, as well as the costliest (virtual) materials, are within the reach of dedicated individual artists with good graphics cards and software that is readily available on the Internet. It’s little wonder so many artists are turning it up to 11.

This is not to say that the processes involved are not time-consuming. Fard, for instance, builds her pieces in an engineering-software environment called Rhinoceros, which requires painstaking attention to detail. The resulting NFTs represent views into virtual spaces with their own physics and presence (this is also why they retain their detail under the most rigorous zoom).

A qualified architect with a master’s degree from the University of Toronto, Fard sees her artistic practice as an expression of her Persian-Filipina identity, drawing on the visual traditions of both cultures. “I started with my roots because I think in order to understand others, I have to know myself. And then, from there, the other pieces sort of bloomed,” she says.

Her work can be seen as an expression of an inner world in more than the usual sense. Drawing on her understanding of architecture but released from the demands of physical production, she builds her very own cathedrals, single-handedly, albeit in digital form.

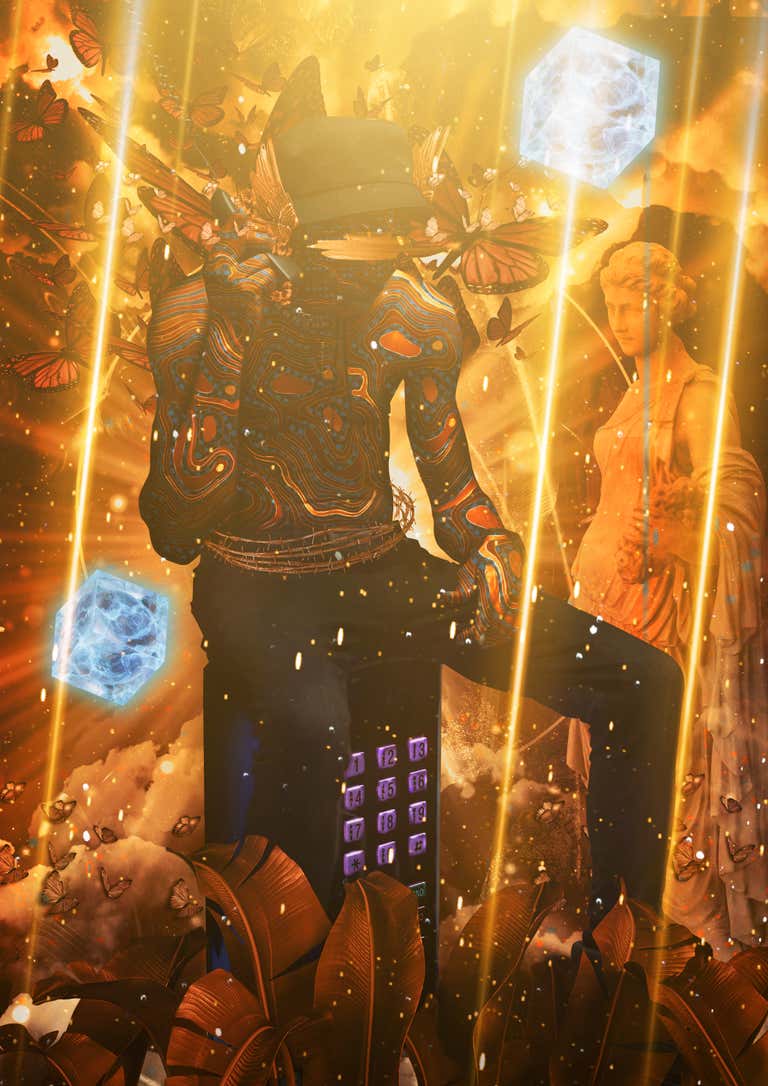

The exploration of a personal mythology is also central to the project of the artist known as Vintagemozart. Originally from Zimbabwe and now based in the United Kingdom, he describes a complex back and forth of influences that resulted in his own take on Afrofuturism.

Although he first became aware of the movement through the visual presentation of American musicians like Janelle Monae and André 3000, he quickly realized that their understanding of it was highly U.S.-centric. His own interpretation of Afrofuturism represents a markedly different counter-factual narrative.

“I’m approaching it not just as if we were never enslaved but as if we didn’t even get colonized and we got to keep our own mythology,” he says. “I started to think that we could have developed like the Greeks and Romans did.”

Vintagemozart’s pieces are exuberant in their detail, with recurrent motifs of Emperor butterflies (“They were around a lot when I was a kid, before climate change,” he says) and rays of golden light. His figures’ bodies are decorated with relief maps of the many places he’s visited, making them embodiments both of the world and of his personal biography, their ebullient smiles — as in as in Black Boy Joy (The Pursuit of Happyness — sometimes reminiscent of Kerry James Marshall.

His work displays a melancholy optimism in its attempt to use digital means to glimpse a history, or even a state of mind, that might have existed were it not for the enduring moral outrage of slavery.

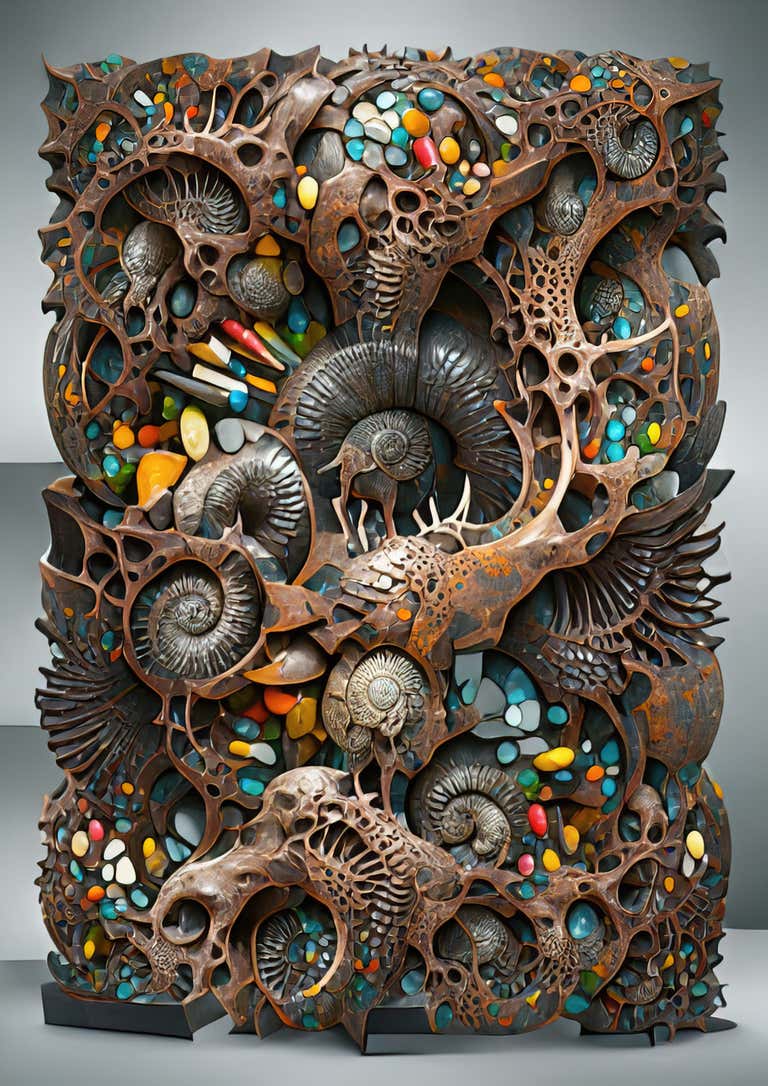

The arrival of AI image platforms like Dall-E, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion may have played a part in the advent of the digital baroque. Since they produce their results by essentially averaging out millions of pictures, they are far better at re-creating an atmosphere or style than they are at arranging individual elements in a picture. Ask Midjourney for something “in the style of Bernini,” and the results are eerily accurate. Ask for a “man eating a cheeseburger,” and the results may be genuinely alarming.

“It’s very easy to produce cursed images,” says the digital artist known as Unlimited Dream Co., “because the AI has no taste, it has no judgment.” So, he is turning the relationship with the AI into a kind of dance. He makes his pieces by feeding his own drawings into Stable Diffusion alongside art-historical prompts.

He then repeats the process with the resulting images until he achieves the outcome he’s looking for. “I’m not just typing in a phrase and seeing what pops out. I’m trying to work out how do I guide it,” he says.

His NFTs, such as Cathedral, are a true collaboration with the AI, or even a kind of communication with something mysterious — that is, the latent space in the AI’s understanding of art history. “It has distilled the essence of 200 million images into a probability space, of every image and every image in between,” the artist explains. “So, it’s very interesting to project yourself into that. To kind of fish around and see what’s in there.”

For 25-year-old artist Tetra, the allusion to the baroque doesn’t come as a surprise. “I’ve been into Caravaggio from young,” he says, citing Virgil Abloh’s streetwear designs as his introduction to the Italian master. A first-generation American of Cuban and Dominican descent, he synthesizes diverse influences in his work, including video games and anime, as well as Renaissance art.

Working in Photoshop, which he mastered in his teens, Tetra combines these precedents into seamless digital collages. These are notable for their reproduction of painterly effects like brushstrokes and the patina of old canvas, which, in a kind of digital double bluff, he renders in painstaking detail through the application of textures.

“I try so hard to make my pieces indistinguishable from hand-painted pieces because I want to show all the experiences that I’ve had that go into making them,” Tetra says. He compares his works to the images that accompany a major movie release, “when they have a still frame of something grand, something insane happening. That’s what I want my pieces to be.” As a metaphor for the power of the baroque to evoke a broader mythology, the artwork as merely the tip of the iceberg, it’s worthy of Caravaggio himself.

But just as the baroque was a kind of exponential advance on classical forms of art, so these artists’ digital works push current technologies to maximal effect. As Unlimited Dream Co. puts it, “We’ve got these new tools. What can we do with them?”

Nevertheless, these crypto creators retain some of the elements of the original style — the evocation of awe at the ineffable, the caking on of detail and high-status materiality — but turn them to more personal ends. Instead of demonstrating the power of a hegemony, they show the power of technologically enabled individuals in their pursuit of a mythology that can express their own inner worlds.