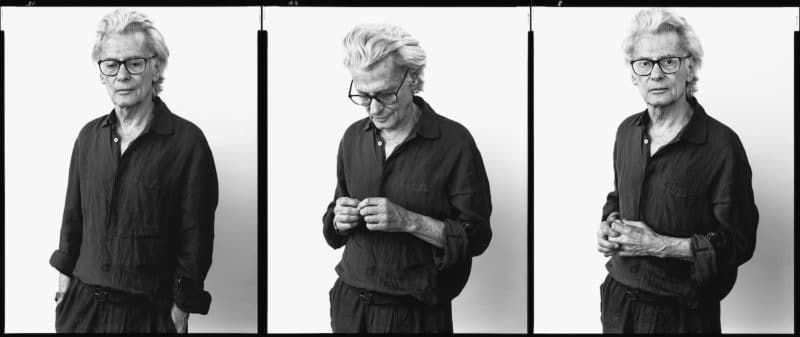

Richard Avedon, photographer, New York City, May 31, 2002, a self-portrait by the artist. All photos are by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation

A while back, Richard Avedon had a confession to make. “I hate cameras,” said the man who revolutionized fashion and portrait photography. “If I could only work with my eyes alone!”

Yet Avedon’s photos seem to do just that — they remove the distance the camera lens creates to make you feel that you are right there beside his subjects.

From August 12 through October 9, the Guild Hall Museum in East Hampton, New York, is presenting “Avedon’s America,” a selection of black-and-white portraits that offer insight into the people (famous and ordinary) who shaped the United States of the mid-to-late 20th century.

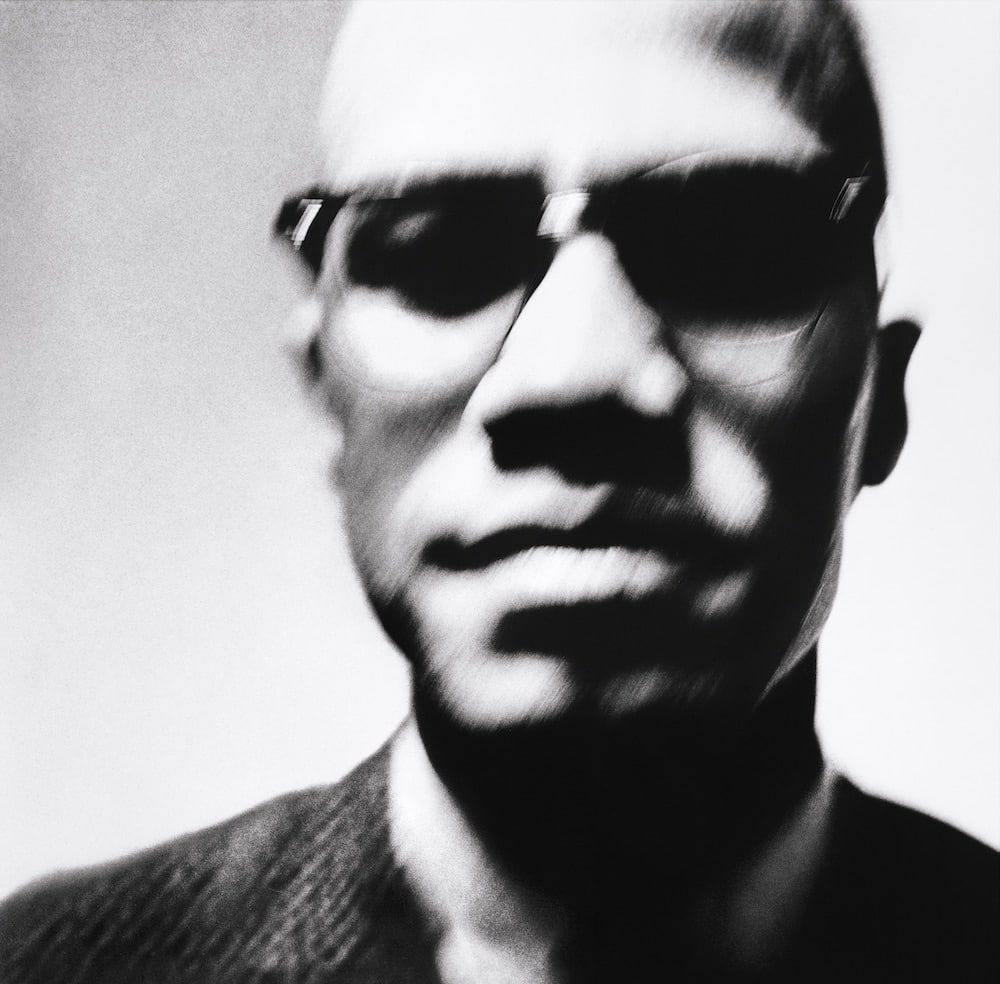

Malcolm X, civil rights leader, New York, March 27, 1963

Deciding what to include was an exercise in editing. “You could easily fill up a whole gallery” with just images from the 1940s, said James Martin, executive director of the Richard Avedon Foundation, which co-organized the show. The images they chose are breathtaking conversation-starters.

Born in New York City in 1923, Avedon had a stern father, an artistic mother and a beautiful, but troubled, sister. At 18, he wanted to be a poet. And the slight, 5’7” dreamer didn’t lack confidence — or a sense of drama. “I know my drifting will not prove a loss / For mine is a rolling stone that has gathered moss,” he wrote in 1941.

A year later, Avedon joined the Merchant Marines, where he spent his World War II years shooting ID photos of new recruits. “I must have taken pictures of 100,000 faces before it occurred to me I was becoming a photographer,” he later recalled.

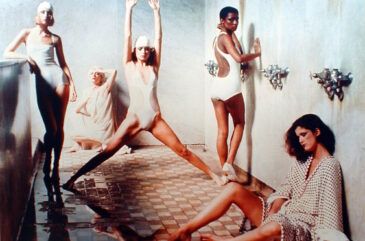

China Machado, evening pajamas by Galitzine, London, January 1965

After demobilization in 1944, Avedon shot fashion pictures for the tony Manhattan department store Bonwit Teller and studied with Harper’s Bazaar art director, Alexey Brodovitch. By 1945, his work was appearing in Junior Bazaar. “His first photographs for us were technically very bad,” Brodovitch later recalled. “But they were not snapshots. . . . Those first pictures of his had freshness and individuality, and they showed enthusiasm and a willingness to take chances.”

Who else was willing to take chances? Brodovitch and Carmel Snow, editor in chief of Harper’s Bazaar, who soon sent the young talent to fashion’s sacred capital, Paris.

The postwar years were hard in Paris. When Avedon first arrived there, in 1946, it was with an explicit directive from Snow. “Dick was tasked with this idea that he was there to rebuild Paris,” explains Martin. In restoring the energy and excitement around Paris, Avedon imbued it with some of his own.

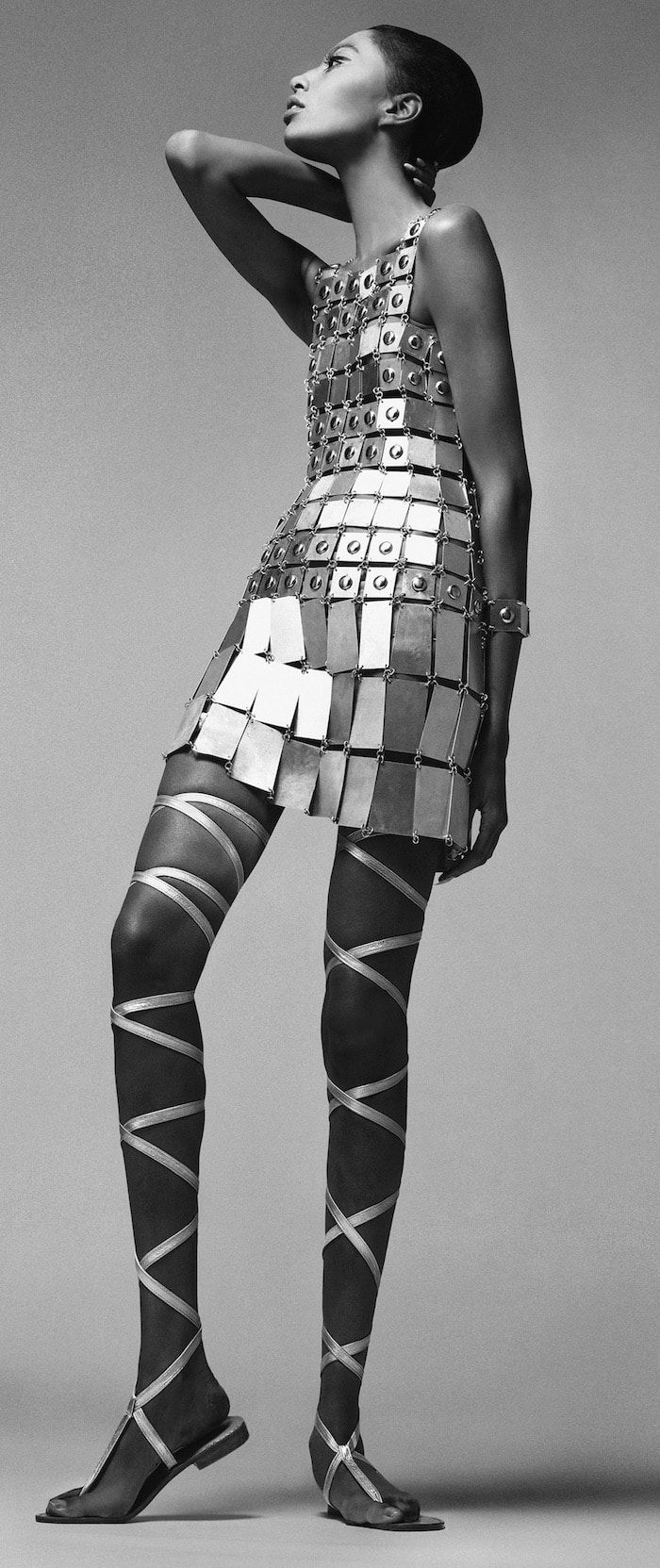

Donyale Luna, dress by Paco Rabanne, New York, December 6, 1966

Avedon’s models jumped, twirled, leapt over puddles and they smiled. Like Avedon himself, they rarely stood still. While he wasn’t the first to use action in fashion photography (in the 1930s, Martin Munkacsi and Toni Frissell began creating fashion images of women engaged in sporty scenarios), Avedon was the first to pair such vitality with women wearing couture.

Character and spirit became la mode. Dovima’s graceful silhouette juxtaposed against the wrinkled heft of two shackled elephants. Dorian Leigh laughing and embracing a bicycle racer. Suzy Parker roller skating across the Place de la Concorde. Sunny Harnett and her cool gaze just daring the roulette table — and every man in the room — not to do her bidding. There was always a narrative in an Avedon mise en scene — whether the background was elaborately staged or stark, the model’s job had forever changed from posing, to acting.

Avedon had everything to do with this. Said one model, “Dick could make a stone respond.”

The Generals of the Daughters of the American Revolution, DAR Convention, Mayflower Hotel, Washington, D.C., October 15, 1963

Of course, Avedon did not limit himself to fashion photography. The little boy who once collected autographs grew up to create the most iconic portraits of the 20th century, many of these are included in the exhibition.

A 1958 New Yorker profile noted that even though Avedon’s portraits immortalized cultural elites such as Truman Capote, Elsa Maxwell and Charles Laughton, the qualities that most interested the photographer were “advanced age, physical debility, ugliness, or the pathos underlying the surface insouciance.” Yet “none of Avedon’s subjects seem to resent this kind of treatment . . . being selected to sit for one of his Harper’s Bazaar portraits ranks as an accolade.”

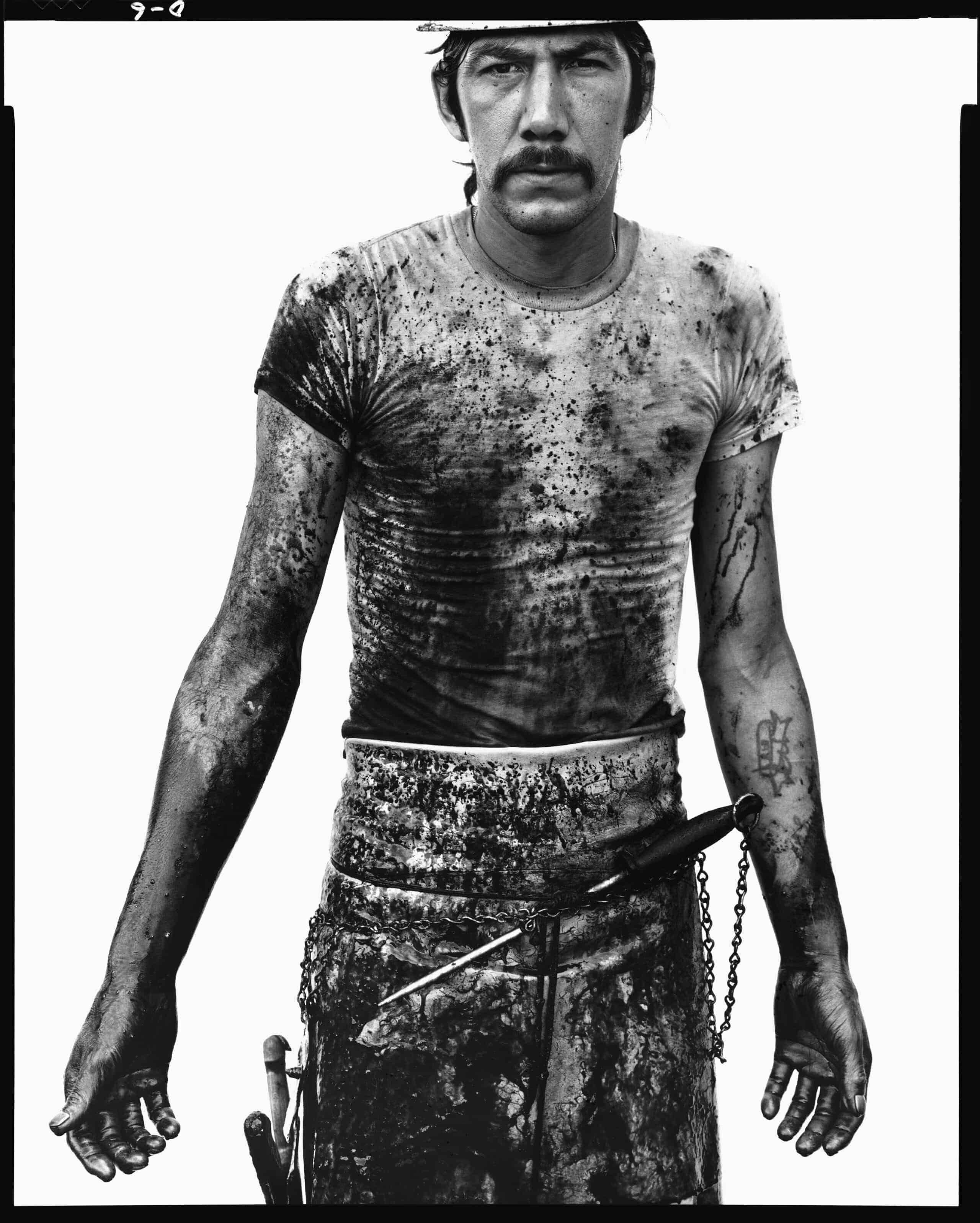

Blue Cloud (Larry) Wright, slaughterhouse worker, Omaha, Nebraska, August 10, 1979

Over the next 40-plus years of his career, his iconic portraiture never lost its force; although at times, his unvarnished truth felt cruel. His photographs of Americans, says Martin, are not “a glamorized fiction of what it means to be American.”

Instead, the exhibition features citizens of “an odd and quirky and strange and complicated place.” Undoubtedly, it’s a description that holds true today.

But Avedon was a creator, not an observer, and he made no apologies for this. The sitter and the photographer “have separate ambitions for the image,” he wrote in 1985. “His need to plead his case probably goes as deep as my need to plead mine, but the control is with me.”

Avedon died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 2004 while on assignment for the New Yorker.