Way back in the early 1980s, when I was an editorial assistant at Vogue, my boss asked me to go to the apartment of the fashion photographer Deborah Turbeville to pick up a parcel from her on my way to work the following morning. I can’t remember why the parcel couldn’t be sent by messenger — Condé Nast had its own fleet of cyclists — but looking back on it now, turning a mundane and anonymous task into a personal rendezvous was very much in keeping with who Turbeville was.

I had been in awe of her since my teens, when she rocked the fashion world with one of her early assignments for Vogue, a 10-page spread of swimsuit-and-beachwear-clad models shot in an aging bathhouse in lower Manhattan in 1975. The images were grainy and faded, and the quintet of models looked languid and dreamy, barely aware of the photographer, much less each other. Although beautiful, they weren’t presented as a gathering of beauties, but as isolated individuals. For Vogue, this was a radically new way of portraying women, and many readers responded with outrage. Some charged the images evoked Auschwitz (really?), others that they suggested some kind of lesbian brothel (oh, the days before the The L Word!), or a decrepit asylum (there was some truth to this one, but the patients were so well dressed!).

If my memory is correct, the controversy was even reported on the six o’clock news. What’s doubly ironic, looking back on it now, is that while readers were often shocked by the decidedly erotic, if witty imagery of Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin, then the reigning kings of fashion photography, their highly polished kink never created the same scandal as hers. Sexually objectifying women was not just expected, but socially acceptable back then. However, to suggest the interior life of a group of women who seemed uninterested in the camera or their pretty clothes was deeply disturbing.

As a young woman, I was as ardent about feminism as I was style-obsessed, so Deborah Turbeville was a revelation. Apparently, she was too for Alexander Liberman, the legendary creative director of Condé Nast, who had commissioned the shoot. So impressed was he by her bathhouse images, and delighted by the ensuing controversy — not to mention the resulting publicity and issue sales — he immediately sent her off to Paris to shoot the collections. Thus, Turbeville established herself as one of Vogue’s most acclaimed photographers.

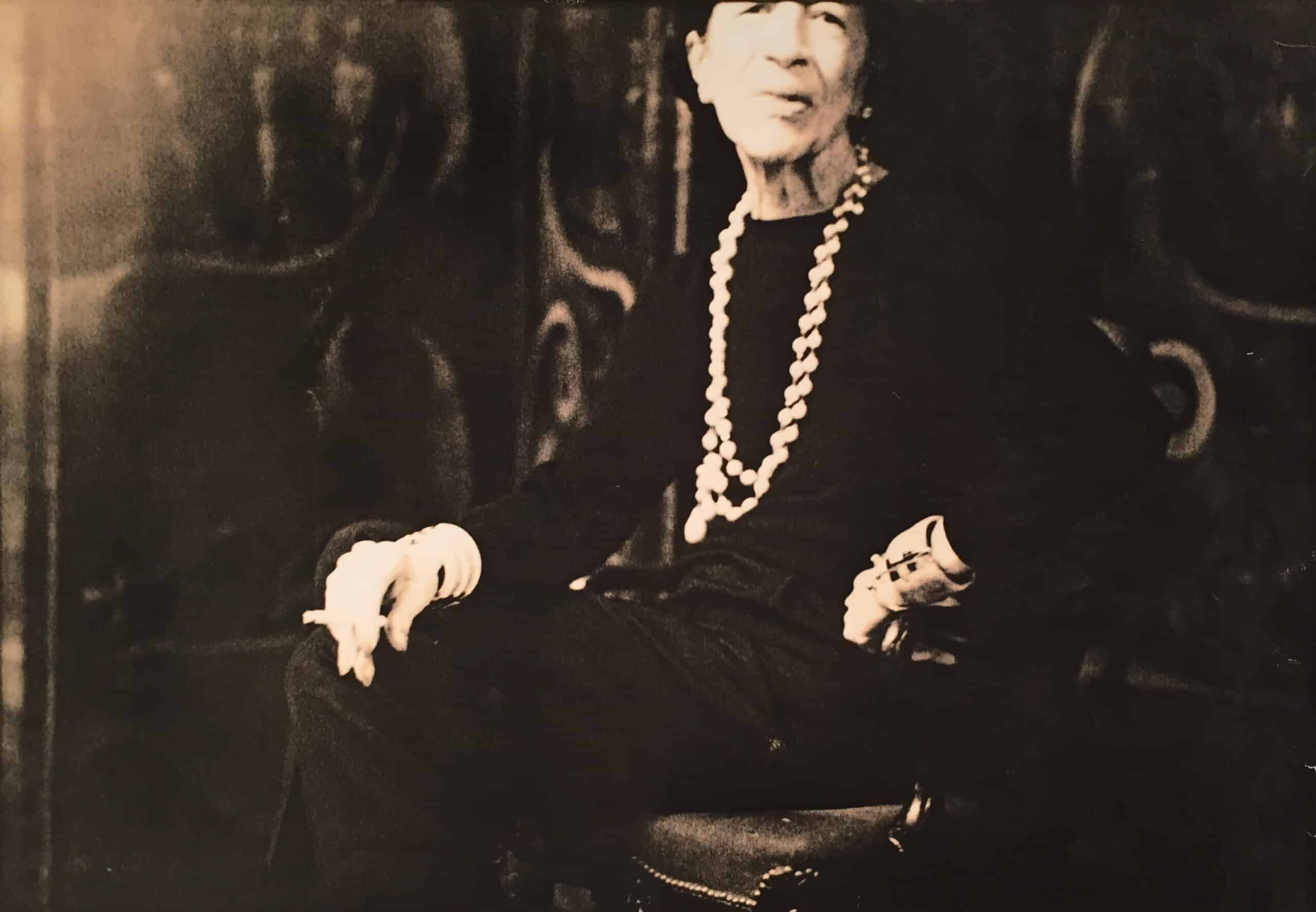

When my boss assigned me my Turbeville errand, I remember she let me in on a little gossip. Turbeville, then in her early 50s, had a much younger boyfriend, who was very good-looking and macho. Friends of the couple referred to them as “Blanche and Stanley.” Now I was even more intrigued by this tall, lanky woman, with the wispy, reddish, Sonia Rykiel-style hair and black wardrobe. I was thrilled that a mature woman with a singular and subversive vision might have some virile young guy as a boyfriend. In a kind of surreal Tennessee-Williams-meets-Nancy-Meyers touch, I discovered the next day that Turbeville lived in the Ansonia, a fantastical turreted wedding cake of a building on the Upper West Side, and her apartment was not only cozy in a kind of late 19th-century Russian style, with scavenged furnishings from her travels, but also included one of the turret’s round rooms.

I don’t remember much about our encounter, other than being entranced by the ambiance. It was a gloomy winter day, and the gray morning light filtering into the apartment was just like that in Turbeville’s pictures. It was as if she created her own atmosphere. Although our encounter was essentially perfunctory, I was entranced to meet this idol, but I also remember being deeply disappointed I didn’t get a glimpse of “Stanley.”

To judge from her origins, Turbeville was destined to be either an outcast or an artist. Her mother and her sisters lived in a large house outside of Boston that they had inherited from their wealthy father, who had spent time in Paris trying to be a painter, and the siblings prided themselves on their superior cultivation and discriminating taste.

Theirs was a Boston Brahmin feminine hothouse that suggests a tale worthy of Edward Gorey. When Turbeville’s mother married, her Texan-born husband came to live with the sisters, and it was in this eccentric household that Deborah Turbeville, born in 1932, was raised. “Don’t ever try to be like others, strive to be yourself, be original,” was her mother’s frequent admonition. Deborah Turbeville did not disappoint.

An only child, she went everywhere her parents went, and quickly developed sophisticated tastes and strong opinions. Her mother described her as “a shy and scary child.” Asked to make a drawing about Christmas or America when in grade school, Turbeville produced a picture her teacher found so disturbing that she was suspended from school for several weeks.

Turbeville would later relate how the old sections of Boston, the cobblestone streets, the fog and snow all made deep impressions on her, so too did the family’s summer home in picturesque Ogunquit, Maine. While she acknowledged its beauty, she described the locale as “very sorry, very sinister…” She would later evoke these places and moods in her images of abandoned resorts and deserted beaches. “I have an instinct for finding the odd location, the dismissed face, the eerie atmosphere, the oppressed mood,” Turbeville said.

Turbeville didn’t take to college. She left when she was 20 and moved to New York in hopes of becoming an actress, but instead got a job as an assistant and fittings model for Claire McCardell, then a pioneer of ready-to-wear and the designer of choice for a new generation of active, stylish American women. She greatly admired McCardell, but left to work in magazines, eventually landing a job as a fashion editor at Harper’s Bazaar. As only might happen to her, on a children’s fashion shoot in Texas, she and the photographer were arrested when they trespassed on a playground. The incident resulted in her being fired.

Fed up with photographers, Turbeville decided to learn to take photographs herself. When she bought her first camera, a Pentax, around 1966, she asked the man in the camera shop to teach her how to use it. But make no mistake her blurry, grainy images were not the result of incompetence, but focused intention. Some of the era’s top lens men, particularly Richard Avedon, served as her mentors, impressed by the cinematic quality and poetic insight of her vision. Years later, in her introduction to Turbeville’s 2009 photo book, Past Imperfect, Franca Sozzani, then the editor of Italian Vogue, noted that “Every detail is perfect and wrong at the same time.”

In 1971, for her first Vogue shoot, Turbeville posed models in Geoffrey Beene dresses outside a cement works. But she didn’t solidify her association with the magazine until the bathhouse shoot. Idiosyncratic and mysterious, her feminine gaze profoundly altered the course of fashion photography during that decade and beyond. Traces of her eye are in every fashion image of a pale, haunted-looking model in a desolate landscape or dilapidated building. So captivated by her vision was Jackie Kennedy Onassis, then an editor at Doubleday, that in 1979 she commissioned the picture book Unseen Versailles from Turbeville. She asked her “to conjure up what went on there … to evoke the feeling that there were ghosts and memories.”

Turbeville spent two years on the project, much of it researching the lives of the mistresses of the various Louis and exploring the forgotten spaces in the palace, the attics and store rooms, much to the consternation of the officials at Versailles. (Kennedy Onassis needed to play diplomat on several occasions, smoothing ruffled feathers on what were then very expensive long-distance calls.)

The spectral images Turbeville shot — some of derelict, lonely spaces and others with obscure figures in them or the gardens of Versailles in winter — express the expectancy, boredom, loneliness and melancholy of the ladies of court, whose privileged, but debilitating, existence was predicated entirely on their adding sparkle to the life of the sovereign. It was the Versailles no one had ever seen, much less conceived. The finished product was a sensation and won the American Book Award.

Many critics deemed the photographs “romantic,” but Turbeville bridled at the term. “I’m not a romantic photographer,” she told one interviewer. “I want to get on people’s nerves. Eerie. Not definitively eerie like Joel-Peter Witkin … mine is a more subtle way.” If her work was to be construed as “romantic,” she said it was in the 19th-century sense of the word. She wanted to be likened to Charles Baudelaire and Edgar Allen Poe. Other books followed, most notably, Studio St. Petersburg. Later, Turbeville took to crumpling and otherwise damaging her images, so that, as she put it, “you never have it completely there.”

“She was an original. Do you know how rare that is?” asks Etheleen Staley, one of the founding directors of the Staley-Wise Gallery, which specializes in fashion photography.

“When we opened our gallery thirty years ago, Deborah was one of the photographers we most wanted to work with. She was a real artist, fashion was incidental to her art.” Staley concedes that Turbeville is not the most widely collected of the gallery’s artists —“She’s not Herb Ritts”— but among the most discriminating connoisseurs, she is a favorite. Deborah Turbeville died in 2013 after a long battle with lung cancer.

Earlier this summer, Staley-Wise Gallery presented an exhibition of Turbeville’s fashion photographs, including her photos of famously “anti-fashion” Comme des Garçons clothing, in conjunction with the Metropolitan Museum’s Rei Kawakubo retrospective. The Paris Review in 1977 published Turbeville’s “ideal fashion magazine,” where women are vulnerable, perhaps a little fallen, and oddly not fashionable. In the left-hand corner of the second spread of “Maquillage,” there’s a handwritten note that reads, in part: “I feel that New York is a house of Death — people shatter there so easily — evil gets into the bloodstream — unhappiness is more catching than laughter.”

In the duplicate images underneath, we see three women in white, their faces obscured: one is standing with her foot on a stool, looking out of a large, bright window; another sits facing the camera; a third rests behind the sitting woman — we can only see her elbow, which stabs out from her side like a lance (her hand is on her hip). Her foot rests next to her, delicately slipping out of a shoe. Their clothes are in shadow, but the light from the windows is blinding. They are women in a dream.

It is an unorthodox vision, at once haunting and memorable. The characters (mostly women) interact with their strange, elusive environments as anachronisms; misplaced, out of sync with their time and context. A group of Turbeville’s favorite actresses and models (mostly unknown) act as a repertoire cast who interpret these endangered species. Mutations in a mannequin workshop, statues in a Paris art school, automatons in a derelict factory. They reveal inner thoughts, emotions, and a sense of unease. There is a sense of fragmented dreams, dislocation, hallucination, a time without boundaries — ongoing — the past imperfect.