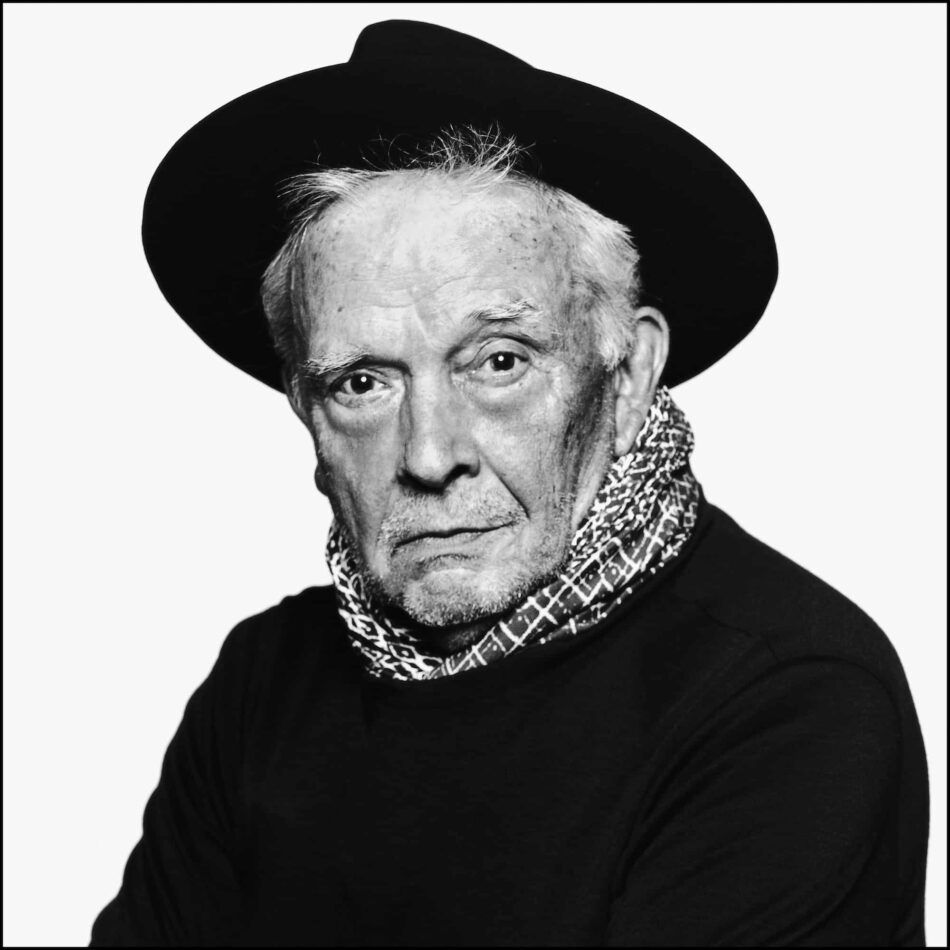

If ever there was an outsize talent who deserved an outsize book, it is the British photographer David Bailey. And now he has one. Taschen has released David Bailey SUMO, a signed, limited-edition retrospective of the legendary lensman’s work with more than 330 photographs, selected by him from his own personal archive, documenting his more than five-decade-long career.

So ginormous is this tome that it comes with its own Marc Newson–designed stand. Artist Damien Hirst, whom Bailey has photographed often, sometimes outrageously, offers an affectionate forward as one cheeky self-made bloke about another, while photography expert Francis Hodgson adds critical heft to the already weighty volume with a three-part essay.

At 15, David Bailey was jazz mad and Picasso loving but, being a dyslexic cockney, was booted out of school. Escape from gritty East London seemed unlikely until he picked up a Rolleiflex during his stint in the National Service. Three years later, in 1960, he was under contract at British Vogue.

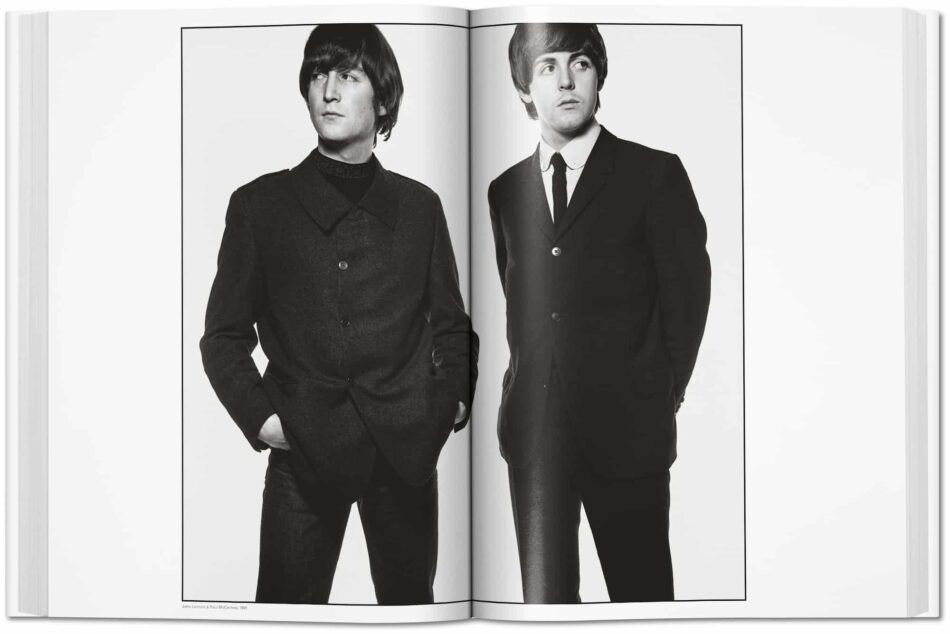

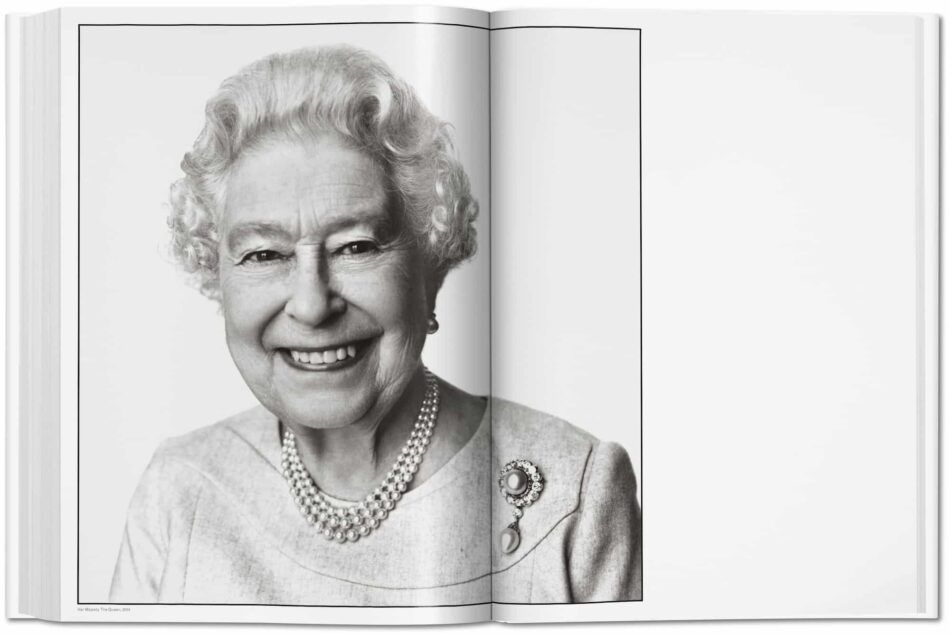

Prodigiously talented, Bailey was also wildly charismatic and uncommonly pretty, a high-octane amalgam that no doubt fueled his meteoric rise. Soon, he was chronicling, and surfing, the cultural tsunami that transformed London in the Swinging Sixties, when young creatives from music, fashion, advertising, theater, film, TV and journalism toppled the British establishment to become the new royalty.

This was the moment when the seeds of celebrity culture were sown. Bailey snapped all these revolutionary aristos: John Lennon and Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger, Michael Caine, Tom Stoppard and David Hockney. Each and every one looks impossibly dewy and fresh and brims with an entirely modern derring-do.

So, too, do “the beautiful birds,” as Bailey called the alluring models and actresses who defined that decade: the exquisite Jean “Shrimp” Shrimpton, Twiggy, Penelope Tree, Brigitte Bardot, Jeanne Moreau, Catherine Deneuve. A number of them became his lovers, Deneuve his wife (he’s had four), for a time.

It was a wild ride for an East End lad and literally the stuff of movies. Bailey was the inspiration for the prowling fashion photographer Thomas, played by pretty boy David Hemmings, in one of the iconic films of that era, Antonioni’s Blowup.

Gossip aside, David Bailey, now 82, can snap like few others. His closest peer in spontaneity, insight and cool was Richard Avedon. Both preferred a white backdrop, strong lighting and a tight focus to capture that rare telling moment.

Someone shot with eyes shut is not an accident with Bailey but a revelation. To this day, he can’t explain how he works his magic, although he does liken it to shamanic conjuring. He makes no secret that he spends most of his time gabbing with his subject — he’s curious about everyone. Sometimes, the chatter is a seduction; occasionally, it becomes good-naturedly pugilistic. And then, in mere moments, the individual is sized and seized by his camera.

Despite his playboy persona and lucrative work in fashion advertising, Bailey has always possessed real psychological depth and artistic ambition. In the book, you see it develop in his increasingly complex portraits of women, especially those of his fourth and present wife, Catherine Dyer, and daughter Paloma. Also moving is how he has continued to lovingly photograph his exes, like Shrimpton and Deneuve.

One senses that as much of a rogue as Bailey was with women, he was also a mensch. His 1966 photograph of the fashion writer Marit Allen, naked and great with child, is full of warmth and admiration and certainly “inspired” Annie Leibovitz’s sensational Vanity Fair cover of the pregnant Demi Moore. More recently, portraits of Zaha Hadid and Marina Abramović show these women as girlish, with the kinds of smiles that finish a bout of giggles, but not in a way that strips them of their stature.

Similarly touching is how lovingly and playfully Bailey has shot gay men. There are two photos of him in bed with Andy Warhol, who is pretending to be asleep. Other portraits of Warhol in the book strip him of his psychic mask but without leaving him bare. Hodgson suggests that Bailey has always felt a certain camaraderie with gay men because he, like them, was an establishment outsider.

Yet there is a competitive edge to some of these photos, like the double portrait he shot with a high-camp Cecil Beaton in white suit, shoes and fedora. Beaton is seen in the mirror behind Bailey taking a photograph of him, but it is the studly cockney with long black hair, black turtleneck and black leather pants who gazes out at us, slyly announcing himself as the new master of the society portrait.

Bailey may have left school early, but as this book proves, the legendary photographer never stopped schooling his eye.