Abstract art, in its many forms, has long fascinated collectors, curators, designers and museumgoers. Free from the constraints of realism, abstraction invites a deeper, more personal engagement — one that allows both creator and viewer to explore style, color and emotion in their purest form.

From the bold geometry of Kazimir Malevich to the meditative Color Fields of Mark Rothko, abstract art has shaped visual culture for more than a century, redefining beauty and meaning. It also has the power to transform interiors; abstract works serve as focal points, infusing spaces with intellectual and emotional depth, whether they’re Jackson Pollock‘s action paintings, with their rhythmic intensity, or Henri Matisse’s fauvist compositions, with their vibrant harmonies. Today, abstract art is as relevant as ever, the subject of blockbuster museum and gallery shows and highly sought after by both institutions and private collectors.

Here, we explore the key movements and their impact on the worlds of design and collecting.

Geometric Abstraction

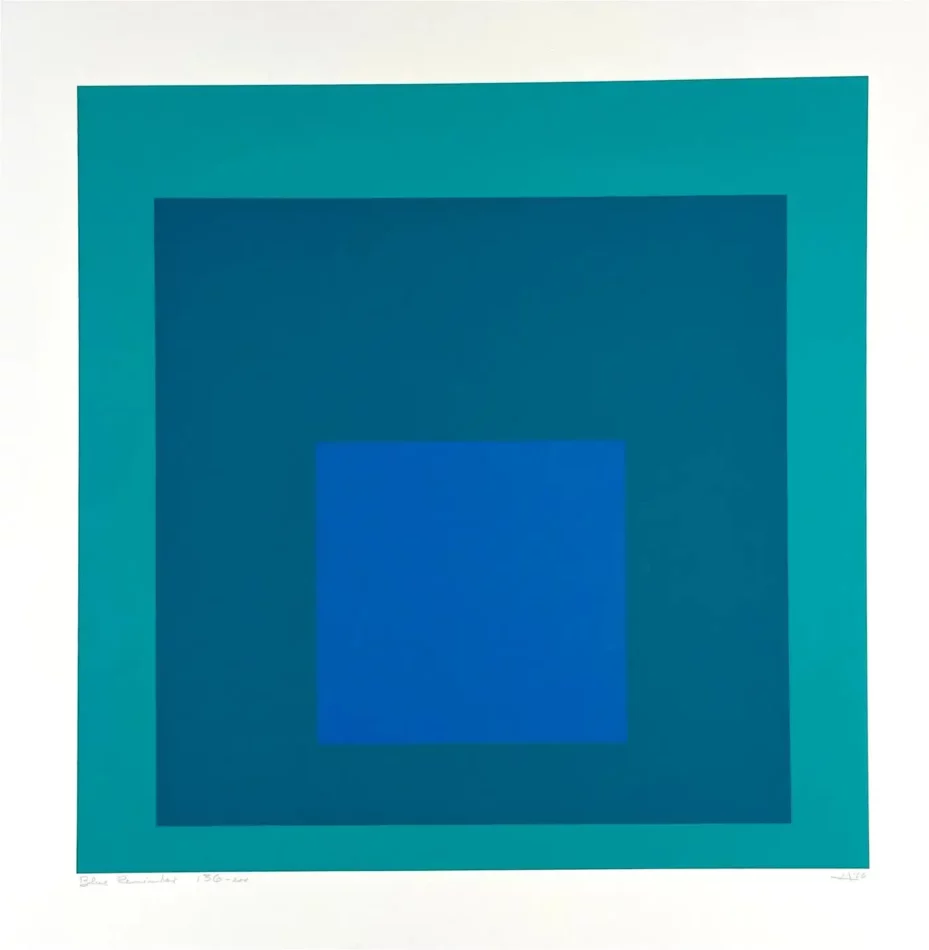

A bold departure from realism, geometric abstraction emerged in the early 20th century as artists sought to break free from representational art and embraced mathematical precision. Espousing purity of form, color and composition, its main tenet was to distill the visual world into clear shapes and lines, forming striking contrasts. Although rooted in early-20th-century modernism, geometric abstraction largely found inspiration in schools like De Stijl, suprematism and Bauhaus. Pioneering figures like Kazimir Malevich, with his stark Black Square (1915), and Piet Mondrian, whose Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow (1930) epitomizes grid-based abstraction, laid the style’s foundation. Josef Albers, meanwhile, explored the interaction of different colors in his celebrated “Homage to the Square” series, and Frank Stella, through his minimalist hard-edged paintings, pushed geometric abstraction into new territory.

The influence of geometric abstraction extends beyond the canvas, informing architecture, interior design and even fashion. Its clean lines and rhythmic patterns appeal to collectors and design enthusiasts alike. And in contemporary interiors, designers use geometric abstractionist artworks to anchor minimalist spaces or to inject energy into classic decor.

It’s worth noting that geometric abstraction differs from Cubism, another important form of abstraction. Both styles emphasize geometric forms, but with different intent and execution. Cubism, created by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, deconstructs objects into fragmented, overlapping planes to present multiple perspectives while retaining a connection to reality. Geometric abstraction eliminates representation entirely, focusing on pure geometric shapes, color and composition.

Color Field

A significant movement of postwar abstraction, Color Field emerged in the 1940s and flourished through the 1960s, transforming the art world with its immersive swaths of pure, unmodulated hues. The aim was to evoke deep emotional and spiritual responses, shifting focus away from gesture and narrative.

Growing out of Abstract Expressionism, Color Field was developed by artists like Mark Rothko, whose floating rectangles seem to vibrate with emotional intensity, and Barnett Newman, whose “zips” of color slice through fields of pigment, creating a sense of space. Among its adherents, Helen Frankenthaler originated the soak-stain technique, allowing pigments to bleed into raw canvas to produce ethereal compositions that feel almost supernatural. Morris Louis explored gravity and fluidity with cascading veils of color that appear to dissolve into the canvas.

These works, often monumental in scale, cast viewers into a contemplative state: Color becomes the subject, light becomes form. Whether displayed in a modernist penthouse or a serene gallery setting, Color Field paintings have an understated yet powerful presence, proving that pure color can be as evocative as the most intricate detail. (Closely related to Color Field, lyrical abstraction is characterized by a more fluid sensibility, as exemplified in the work of French painter Georges Mathieu).

Abstract Expressionism

A product of postwar America, Abstract Expressionism redefined the essence of artistic expression. The avant-garde movement was less about depicting reality and more about channeling raw emotion into paintings characterized by dynamic brushwork, gestural abstraction and a sense of spontaneity.

At its heart were artists like Jackson Pollock, whose drip works — seemingly chaotic yet deeply intentional — transformed the act of painting into a performative practice. Mark Rothko, for his part, explored color as emotion, creating planes of pigment that invite quiet contemplation. Willem de Kooning employed aggressive strokes and vivid colors in striking a balance between abstraction and figuration.

Although often overlooked in favor of their male counterparts, female artists played a vital role in shaping Abstract Expressionism. Lee Krasner, who married Pollock in 1945, is now considered a master of the style in her own right. Krasner often integrated elements of Cubism and biomorphic shapes into her work, making it individual and distinct from her husband’s. Joan Mitchell pushed the boundaries of color and shape, layering paint with an intensity that evokes both landscapes and emotions.

Abstract Expressionist paintings are often described as feeling “alive,” eliciting visceral responses from viewers. Whether through Pollock’s kinetic splatters or Rothko’s meditative layers, they convey a strong presence, commanding attention in the world’s most prestigious galleries and private collections. Decades after its heyday, the movement continues to shape contemporary art and design, promoting an embrace of texture, movement and emotion.

Minimalism

Emerging in the late 1950s as a reaction against the emotional intensity of Abstract Expressionism, minimalism strips away excess, emphasizing repetition and materiality. Artists like Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Agnes Martin developed the style through pieces that celebrate simplicity while provoking an introspective response.

Judd’s industrial sculptures in aluminum and plexiglass epitomize minimalism’s focus on structure and spatial interaction, while Flavin’s luminous installations — composed entirely of fluorescent tubes — transform environments through color and light. Martin embraced subtlety in delicate, grid-based paintings that have a meditative rhythm. Minimalism’s “less is more” ethos aligns with modern living, especially spaces prioritizing clean lines and an unfussy elegance. Whether expressed in the pared-down serenity of a Tadao Ando building or the hushed sophistication of a John Pawson-designed space, minimalism remains a testament to the beauty of restraint.

Action Painting

A branch of Abstract Expressionism that celebrates movement and emotion, action painting originated in the 1940s and reached its peak in the 1950s. Rather than carefully planning their compositions, the style’s adherents embraced an intuitive, almost elemental practice — dripping, splattering and vigorously applying paint to create works that seem to leap off the canvas.

Jackson Pollock, an icon of Abstract Expressionism, revolutionized painting with his signature “drip” works, created by flinging and pouring paint onto canvases laid flat on the floor. Willem de Kooning combined bold brushstrokes with hints of figuration, while Franz Kline evoked architectural grandeur in dramatic black-and-white compositions.

At its core, Action Painting is about the artist’s physical engagement with a work — an unfiltered expression of emotion captured in real time. Each brushstroke, flick and pour represents a singular moment frozen in paint. The resulting pieces are chaotic yet harmonious, making them ideal for expressive interiors. A Pollock or Krasner instantly transforms a space, adding an electric energy that contrasts beautifully with sleek contemporary furnishings.

Op Art

Op art, short for Optical art, is a visually arresting style, arising in the 1960s, that plays with perception, movement and illusion. Practitioners seek to transform static compositions into experiences using intricate patterns, bold contrasts and geometric shapes. Victor Vasarely, often considered the father of Op art, created mesmerizing designs that seem to shift before the viewer’s eyes. His Zebra (1937) showcases the style’s signature interplay of black-and-white contrasts.

Perhaps the most iconic Op art creator, Bridget Riley brought a refined, almost hypnotic elegance to the genre. Her paintings, including Blaze (1964), produce a dizzying effect, challenging the eye with oscillating lines and kinetic energy.

Op art received mainstream recognition with the 1965 MoMA exhibition “The Responsive Eye,” which solidified its place in contemporary culture. For interior designers, Vasarely’s optical illusions remain a source of inspiration, expressed in bold wallpapers and textiles that imbue spaces with a sense of flow.

Surrealism

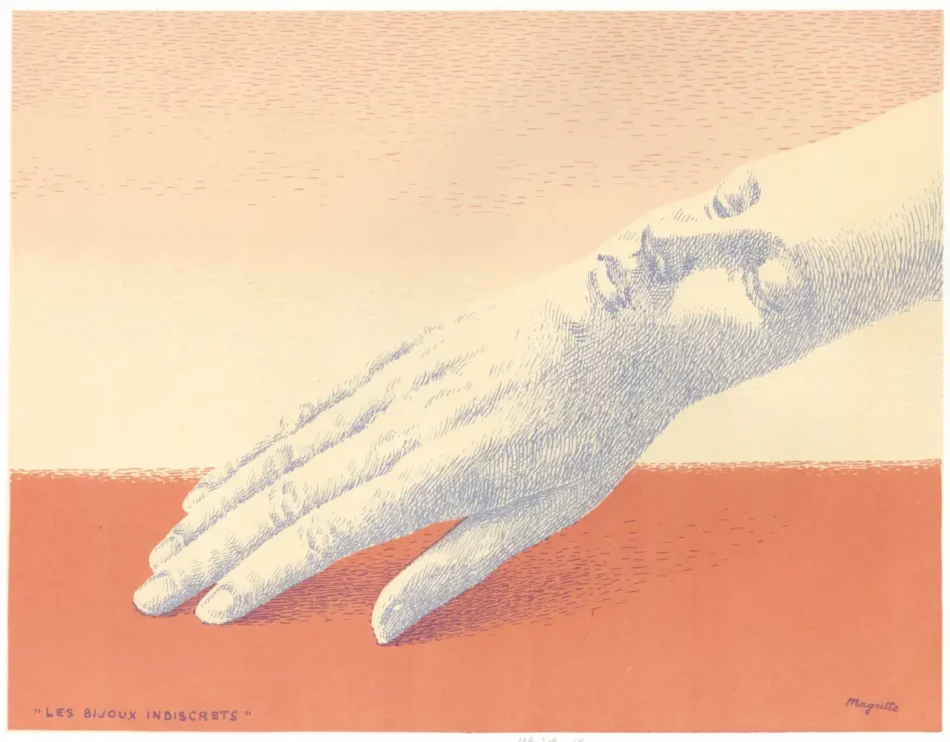

A boundary-pushing movement, spearheaded by André Breton in the 1920s in the wake of World I, Surrealism espouses a dreamlike fusion of reality and the subconscious. It was deeply influenced by Sigmund Freud’s theories on the unconscious mind, rejecting logic and convention in favor of the irrational, fantastical and often unsettling.

Surrealists have produced some of the most evocative and enigmatic works of modern art. Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), with its melting clocks and eerie landscapes, remains an icon of the movement. René Magritte, known for his poetic juxtapositions, crafted thought-provoking pieces like The Son of Man (1964), in which an apple mysteriously obscures a man’s face. Artists like Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington imbue their works with haunting, otherworldly symbolism. Surrealism extended beyond painting into sculpture, photography and even interior design, inspiring whimsical avant-garde aesthetics still seen in contemporary decor.

Fauvism

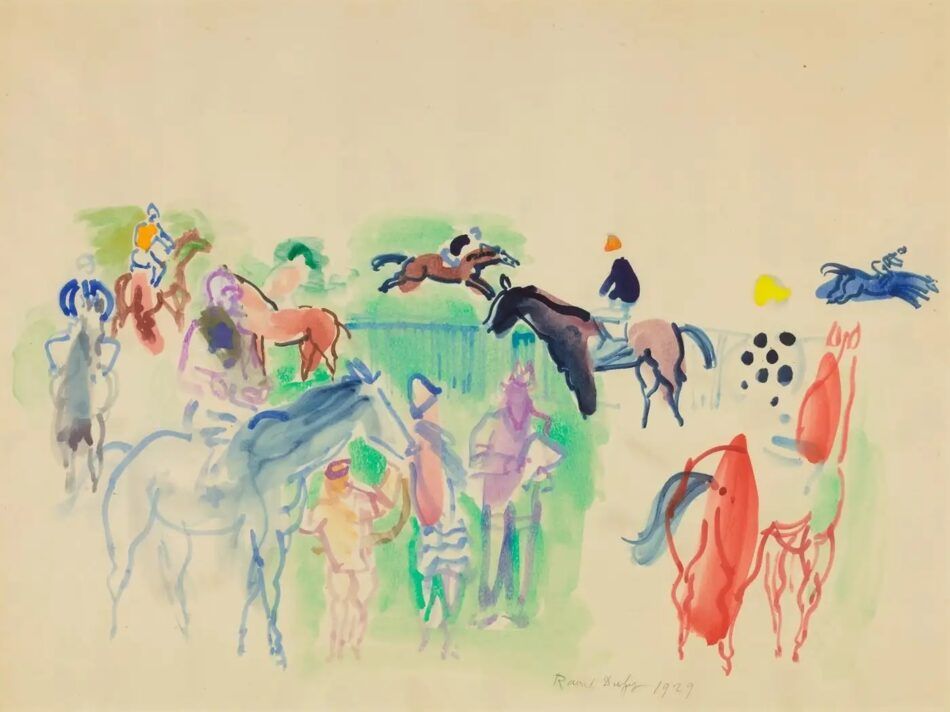

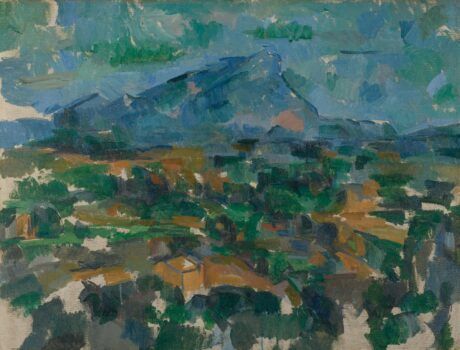

A precursor to modern abstraction, fauvism rejected naturalistic color in favor of wild, expressive hues and emotional intensity. The style was developed by Henri Matisse, whoseWoman with a Hat (1905) and The Joy of Life (1906) exemplify its departure from traditional representation. André Derain, another fauvist master, infused landscapes with electrifying color contrasts, as in Charing Cross Bridge, London (1906). His work, alongside that of Maurice de Vlaminck and Raoul Dufy, portrayed a world saturated in expressive energy, where trees could be cobalt blue and skies a radiant orange.

Although fauvism was short-lived, lasting roughly from 1905 to 1910, its influence on modern art was profound, paving the way for Expressionism and later movements. Its spirit lives on in contemporary interiors, where daring color palettes and unrestrained forms continue to be reference points for many designers. Like a Matisse painting, a fauvist-inspired space radiates a sense of life — proof that color, when used fearlessly, transforms not just canvases but the way we experience the world.

Frequently Asked Questions

What qualifies as abstract art?

Abstract art moves beyond traditional representation, fusing form, color and composition into a visual language that promotes emotion and interpretation. Rather than depicting reality, it invites the viewer into a world of expressive gestures, geometric shapes or something more ethereal. Examples include Malevich’s bold geometries, Rothko’s serene minimalism and Pollock’s organic drips. Defined by its ability to communicate beyond the literal, abstract art transforms space, making it both an experience and an aesthetic statement.

What are the principal forms of abstractionism?

Abstractionism in art takes several forms, but four main types are often distinquished: Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, geometric abstraction and lyrical abstraction. Cubism, most closely associated with Picasso and Braque, deconstructs forms into angular, fragmented perspectives. Abstract Expressionism, championed by Pollock and Rothko, embraces emotional intensity. Geometric abstraction, exemplified by Mondrian’s work, relies on precise shapes and color relationships. Lyrical abstraction, in contrast with the rigidity of geometric abstraction, is more fluid and emotive, evoking mood through sweeping gestures.

What are the different forms of abstract art?

Abstract art manifests in a variety of expressive forms, each pushing the boundaries of visual language. Geometric abstraction, with its crisp lines and bold shapes, evokes a sense of order and harmony, while lyrical abstraction embraces fluidity and emotion through gestural strokes and organic forms. Minimalist abstraction distills composition to its purest essence, often relying on color, space and texture to create impact. Expressive abstraction, embodied in movements like Abstract Expressionism, thrives on spontaneity, with brushstrokes and drips that capture raw energy and movement. And Surrealism transforms objects and organic shapes into dreamlike, otherworldly works.