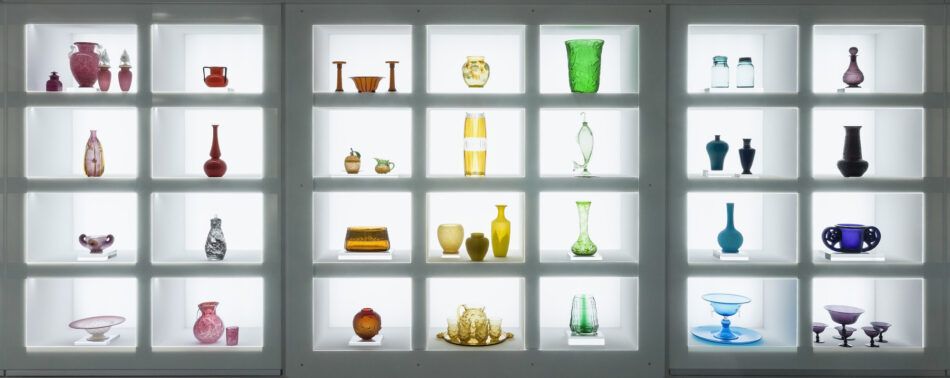

The centerpiece of the exhibition “Brilliant Color” at the Corning Museum of Glass, in Corning, New York, is an illuminated wall of 40-odd cubbyholes, each holding a fine example of a glass vase, compote, candlestick, decanter or perfume bottle. The dazzling installation (by architect Annabelle Selldorf) is organized by hue, according to the colors of the rainbow.

The show, on view through January 11, 2026, traces the chromatic revolution in glass that began in 1856 with the advent of synthetic dyes, which replaced costly, hard-to-source organic ones. Although synthetic dyes could not be used to color glass (they couldn’t withstand the high temperatures required for glassmaking), their discovery led to colorful, affordable designs being adopted in fashion, printed matter and home furnishings. As demand surged for such goods, glassmakers in England, Europe and America increasingly experimented with chemicals and minerals to create glass that looked like emeralds, rubies, malachite, agate and tortoiseshell.

Next to the wall of glass objects is an interactive station where visitors can research the works in the display, filtering them by color, maker, country of origin or decade. The makers include household names like Steuben, Lalique, Baccarat, Saint-Louis, Salviati, Émile Gallé and Louis Comfort Tiffany, as well as lesser-known creatives like Michael Powolny (who produced designs for Johann Lötz Witwe, in the present-day Czech Republic); Klaus Moje (Australia); Maurice Marinot (France); and Leo Moser (of Moser, also in the present-day Czech Republic, who was the exclusive supplier to the Wiener Werkstätte).

“This is the first exhibition that contextualizes glass within the larger craze for color that engulfed the fine and decorative arts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” says Amy McHugh, the curator of modern glass at Corning, who organized the show, her first at the museum. “When color became more affordable, everyone wanted it.” (The show doesn’t engage with Asian glass, because “Asia had very different systems for color creation in glass,” McHugh explains.)

In an essay for the exhibition catalogue, McHugh writes that she decided to approach her subject “by studying the individuals responsible for this explosion of colored glass — the often-overlooked chemists at various glass houses.”

Three of these pivotal figures are profiled in another catalogue essay, by James Measell, a historian at the Fenton Art Glass Company, in Williamstown, West Virginia. The ambitious English immigrants Harry Northwood, Joseph Locke and Frederick Carder arrived on the East Coast of the United States between 1880 and 1930. All were trained at the Stourbridge School of Art, a British-government-sponsored industrial school where they studied chemistry and learned to draw, paint, cut and engrave glass. With a series of innovations, they transformed the industry.

Northwood moved to Wheeling, West Virginia, in 1881 to work for the glassmaking firm Hobbs, Brockunier & Co. Later, he joined the Phoenix Glass Co., in Phillipsburg, Pennsylvania, where he collaborated with Joseph Webb, a fellow Stourbridge alum, who was then inventing compounds to make new tones.

Northwood opened his own factory, in Martins Ferry, Ohio, and introduced ruby red, opaque white and opalescent lemon yellow. Toward the end of his life, he returned to West Virginia and founded the H. Northwood Company, where he developed new iridescent finishes. The exhibition features a footed bowl in the company’s Grape and Cable pattern from about 1910 that is an outstanding example of his popular iridescent “carnival glass.”

Locke, who studied design and engineering at Stourbridge, moved in 1882 to East Cambridge, Massachusetts, to join the New England Glass Co., where he invented and patented Amberina glass, colored by adding pure gold. He also patented the Agata finish, created by coating glass with a metallic stain and spattering it with a quickly evaporating liquid like benzene, alcohol or naphtha, resulting in a mottled appearance. One vase in the show is made of Wild Rose–colored glass with Agata mottling.

Locke traveled to Toledo, Ohio, where he worked at W.L. Libbey & Son Co., then continued his career at the U.S. Glass Co., in Pittsburgh. In 1920, he founded Locke Art Glass, where he introduced acid-etched glass.

The most successful Brit was probably Carder, a chemist, physicist, draftsman, artist and cameo carver who, while still in England, was known for his design sketches and glass works for Russian jeweler Karl Fabergé. When Carder turned 40, in 1903, he moved to Corning, New York, to found Steuben Glass Works.

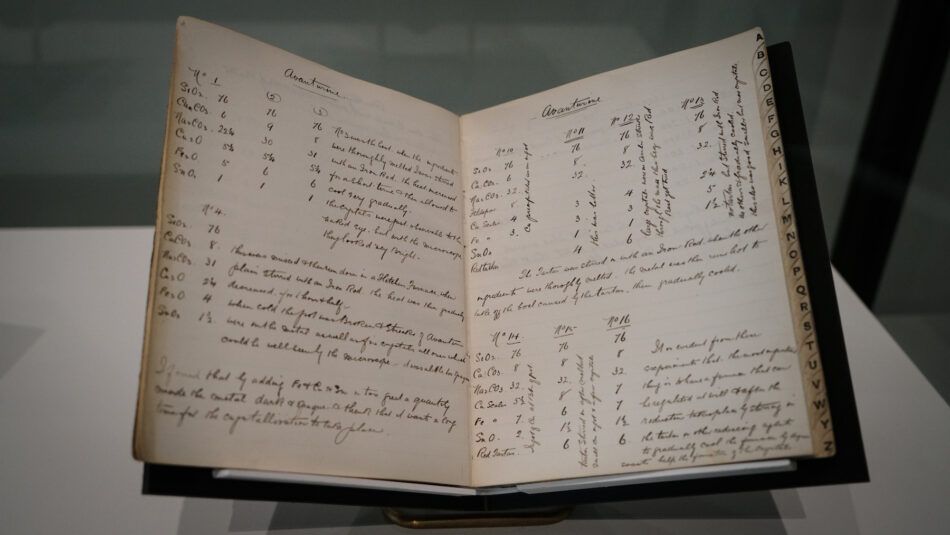

The exhibition includes some of his tiny recipe booklets, called batch books, with painstaking notations of his color formulas — mixtures of ingredients like oxides, chemical compounds and minerals. (Batch books were secret and valuable; some were written in code. One English glassmaker so feared his might be confiscated by U.S. Customs when he arrived in America that he had his wife sew them into her petticoats.)

The result of this industry-wide experimentation was an efflorescence of colorful glass in every part of the home, from dining rooms and kitchens to bathrooms and bedrooms. One corner of the exhibition shows how novel colors and patterns were deployed in interiors, with glass complementing different exuberant wallpaper designs by the 20th-century master of vibrant prints Josef Frank.

By 1940, however, the colored-glass trend was ebbing; it was absent from the New York World’s Fair of 1939 after dominating the Paris Expositions Universelles of 1867, 1878, 1889 and 1900 and the 1925 Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs. Colorless glass had returned to favor. But colored glass certainly didn’t disappear, as evidenced by the jewel-toned works of later artists Eva Zeisel, Toots Zynsky, Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová and Richard Marquis in a small case at the entrance of the exhibition.

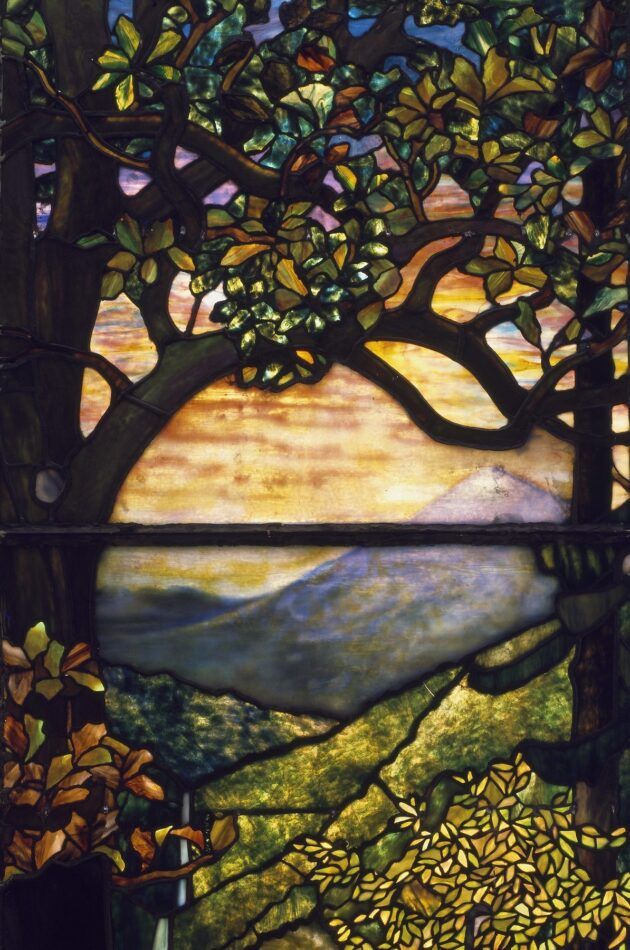

The show ends with a magnificent Louis Comfort Tiffany glass window manufactured at Tiffany Studios in Corona, Queens, New York, in about 1905. It depicts a landscape made of hundreds of pieces of glass in every shade imaginable. It is a fitting conclusion to this fascinating show, and a striking example of the desire to bring more color to the objects that surround us.