For much of the 20th century, it was to Europe — especially England and France — that well-heeled Americans looked for inspiration when outfitting their homes. Of these imported styles, one of the most popular, especially during the postwar period, was English Country House. Mixing period furniture with humble pieces, and silks and damasks with faded chintz and worn leather upholstery in vividly painted rooms, the aesthetic was — and is! — all about taste, elegance, and comfort. While most Americans no doubt imagined this was a traditional English style, the curious truth was that it only emerged after World War I as a response to the new social and economic realities faced by the upper class as a result of the war, and later, the Wall Street collapse of 1929. Perhaps even more surprising, an American was instrumental in both its development and burgeoning.

Nancy Lancaster, the doyenne of English Country House style, in the Entrance Hall of Haseley Court, in the 1950s, in a photograph by Cecil Beaton. The house was her last great home and decorating project.

One of the many blue-bloods who lost a sizable part of her fortune in 1929 was Lady Sibyl Colefax, a London society hostess known for her exceptional taste. In order to preserve what remained of her fortune, Colefax decided to start a decorating business, Sibyl Colefax Ltd. As she had many highborn friends who were in variously straightened circumstances, Colefax developed a glamorous “make-do and mend” decorating style that played up the best of a client’s furnishings, while creating rooms that were relaxed and inviting, as opposed to the cold, imposing and period-obsessed spaces that had long been de rigeur in English stately homes. As Colefax had no professional training, she seemed to rely mostly on her instincts as a hostess. She once quipped, “furnish your room for conversation, and the chairs will take care of themselves.”

Lady Sibyl Colefax, left, with Evelyn Waugh and Comtesse Phyllis de Janzé and Oliver Messel, at right.

A few years into the venture, Colefax brought on John Fowler, a rising talent. Although he came from a modest background, he was highly knowledgeable about upholstery, paint and wallpaper, as well as the history of interior design and architecture. Fowler joined the firm in 1938, and would be instrumental in making it not only one of the best known decorating houses in the world, but also one synonymous with “pleasing decay,” as he teasingly described the English Country House style. Ironically, his collaboration with Colefax was quite brief, as she soon left the day-to-day running of the business to start a soup kitchen when World War II broke out.

Before Fowler’s arrival, one of Colefax’s star projects was Ditchley Park, a splendid Georgian estate. Fun fact: the house plays a role in this season’s Downton Abbey, when the estate’s aristocratic but financially beleaguered owners are forced to sell. When the last heir to Ditchley passed away in 1932, the home was purchased by a wealthy young Anglo-American couple Ronald and Nancy Tree.

Nancy Tree was the daughter of the eldest of the Langhorne sisters, all fabled Virginia belles. The Trees were keenly interested in a new approach to decorating first championed by Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman in their 1897 book The Decoration of Houses that emphasized suitability, simplicity and proportion. In fact, when the Trees had lived in New York, they rented Codman’s townhouse on the Upper East Side and were friends of the society architect William Delano, who was progressive-minded in regard to design, even though he worked in traditional styles. With Delano’s advice, the pair updated Mirador, the Langehorne family’s antebellum plantation house, near Charlottesville.

Mirador, the Langhorne family estate in Greenview, Virginia.

In addition to enlarging and modernizing the bathrooms and brightening the staircase with the insertion of a skylight, they repainted and furnished the rooms with choice family heirlooms and an assortment of faded fabrics and upholstery pieces acquired from estate sales and dealers, so as to maintain the home’s genteel, faded elegance. The groupings of furniture in the rooms, however, were very much in keeping with the spare Parisian-inspired arrangements in Codman’s townhouse. This still unconventional approach to decorating impressed all who visited.

One of the rooms at Mirador after its refurbishment by the Trees.

When it came to Ditchley, as the Trees already had strong ideas and experience regarding decoration, they served more as collaborators than simply clients in developing its schemes with Colefax. Nancy wanted a medley of period pieces including French and Italian in the rooms, especially the bedrooms, as she didn’t think formidable 18th-century English brown wood created the proper ambience. English needlework carpets and damask wall hangings were also her additions, which she felt gave rooms greater warmth and intimacy.

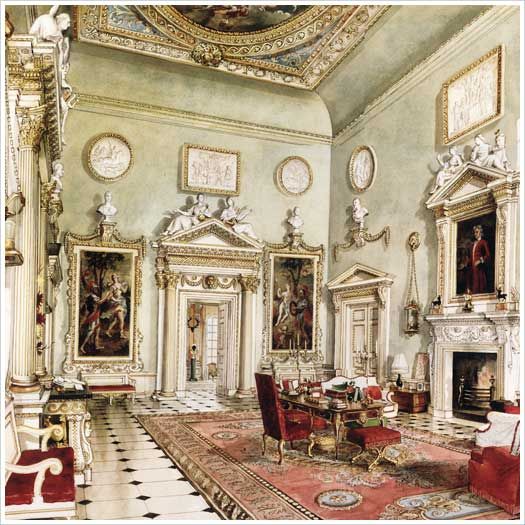

The great hall at Ditchley, designed by Sibyl Colefax in collaboration the Trees. The watercolor by Alexandre Serebrikoff shows William Kent’s paintings of Venus and Aeneas flanking the doorway.

What this talented group accomplished at Ditchley has since been deemed a decorative masterpiece — “an unforgettable picture of magnificence and accumulated junk,” according to one visitor. James Lees-Milne, an architectural historian who visited the house soon after its completion, was duly impressed: “lnside it is perfection. Nothing jars. Nothing is too sumptuous or new.” And yet the house had been thoroughly modernized.

The White Drawing Room at Ditchley.

Recalling weekends there as a girl, Deborah Cavendish, the late dowager Duchess of Devonshire, herself a renowned arbiter of taste, wrote in a paean to Nancy Tree after her death, that “even the bathrooms were little works of art. Warm, paneled, carpeted, there were shelves of Chelsea china, cauliflowers, cabbages, tulips, and rabbits of exquisite quality, a far cry from the cracked lino and icy draughts to which I was accustomed.”

The much-copied blue bedroom at Ditchley Park as depicted in another watercolor by Serebrikoff.

Not many years later, the Trees’ marriage fell apart. In 1944, to give his soon-to-be ex-wife something to do, Ronald Tree bought Colefax & Fowler from Sibyl Colefax, who wanted to retire. And Nancy — who would eventually be known by the surname of her new husband Colonel Claud Lancaster — entered into a richly creative, yet famously quarrelsome partnership with John Fowler. Nancy’s aunt, Lady Astor called them “the unhappiest unmarried couple in England.” Yet they were not without affinities. They shared a similar sense of humor, for instance, making up a private language of colors with names like “mouse’s back” and “dead salmon” and “vomitesse de la reine” and “caca du dauphin.” And they had similar sensibilities about the graceful appeal of age. Nancy would leave new fabrics outside to weather so they would look used, while Fowler, a consummate recycler, often re-dyed old fabrics or spiced up old pieces with new trimmings. In one instance, during the war, when materials were scarce, he made glamorous draperies out of army blankets!

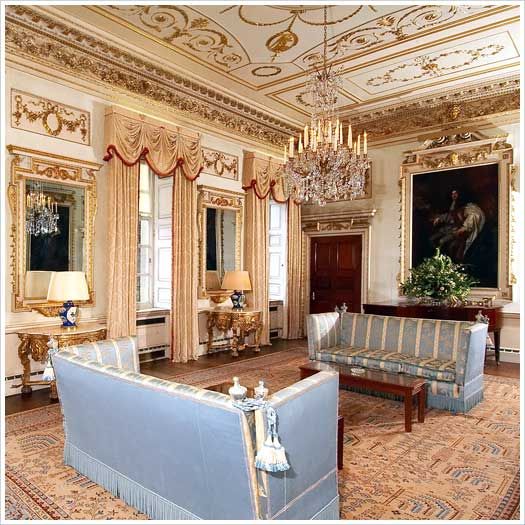

The yellow drawing room at Colefax & Fowler. In describing her approach to decorating, Lancaster wrote toward the end of her career: “You never wanted to have only one mouvement thing, like the Savonnaire rug that would stand out. You must have mouvement everywhere.”

Of all the interiors Lancaster and Fowler collaborated on, perhaps none is more famous than the yellow drawing room in the apartment above the shop on London’s Avery Row, which served as Colefax & Fowler’s office and Nancy’s pied-à-terre. Grandly scaled with 46-foot-long walls and a 14-foot-high barrel ceiling, the room had amazingly luminous buttercup yellow walls, which Fowler achieved through many coats of stippled paint and glaze. Mirrors surrounded the double doors to emphasize the room’s height, while two other circular mirrors high up on either side added to its elegant symmetry.

The room was filled with impressive paintings along with furniture and objects from the shop that hadn’t sold and discarded pieces from Lancaster’s former homes. Guests marveled that the space felt comfortable whether filled with just two people or a partying crowd. Elegant, welcoming and timeless, it was the English Country House ideal.