Baldwin photographed in his New York City apartment in the 1970s.

Billy Baldwin had the unusual distinction of being the first man to break the glass ceiling of interior decoration, which before WWII was ruled by a coterie of ladies. The look he championed in the mid-century was entirely American: classical in foundation, but modern in spirit, free of ostentation and unconcerned with trends. “Be faithful to your own taste,” he used to tell clients, “because nothing you really like is ever out of style.”

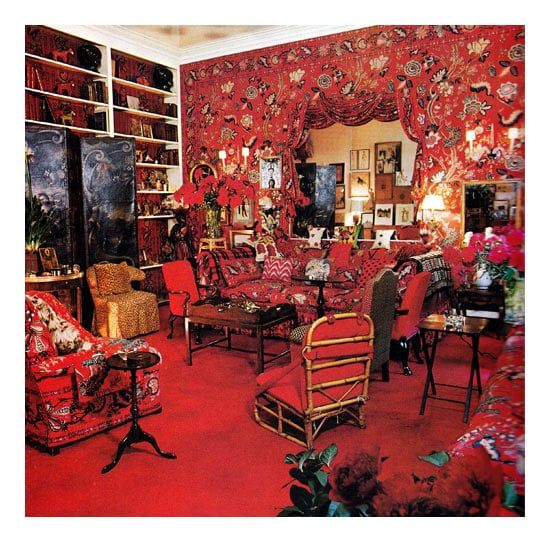

Diana Vreeland requested that Baldwin to transform her drawing room into a “garden in hell.” Baldwin found the perfect blood-red chintz at John Fowler.

By the 1960s, just about every American taste-making blue blood was his client, including Jackie Onassis, Pamela Harriman, Nan Kempner, Bunny Mellon and Babe Paley. If you ever wondered who was responsible for Diana Vreeland’s unforgettable “garden in hell” crimson drawing room, it was Billy B, as his friends called him. “I always say I love color better than people,” he once remarked. He also loved cotton, calling it “his life,” detested damask and satin, and claimed to have “made a lady out of wicker.” His quips were legendary.

Baldwin himself had patrician roots. William Williar Baldwin, Jr. was born to an old Baltimore family in 1903. He grew up in a family manse designed by Charles A. Platt, a leader of the American Renaissance movement, who much influenced his thinking and style. As he would later observe: “We can recognize and give credit where credit is due to the debt of taste we owe Europe, but we have taste too — in fact we’re a whole empire of taste. That is my flag, and I love to wear it.”

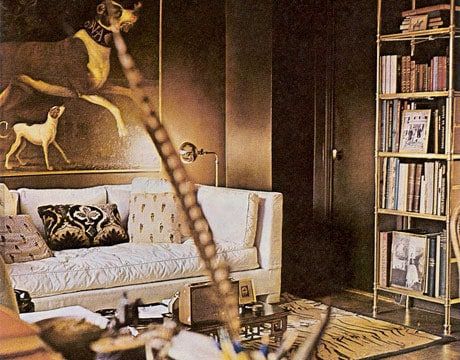

Baldwin created this patterned black-and-white textile, Arbre de Matisse Reverse, to match his client’s Matisse, above.

That said, Baldwin drew inspiration from the Frenchmen Jean-Michel Frank, whom he called “the last genius of French furniture,” and Henri Matisse, whose work he first encountered at ten in the Baltimore home of Etta and Dr. Claribel Cone, the influential art-collecting sisters and friends of Gertrude Stein. He credited Matisse “for emancipating us from Victorian color prejudices” and advocated for his palette of bright, bold hues. Later in life, he would credit that childhood visit for first instilling in him a love of interior design.

Baldwin matriculated to Princeton, where he studied architecture before dropping out in favor of traveling to Manhattan to visit galleries and museums. Without a profession, he returned to Baltimore and went to work at his father’s insurance agency, but also began decorating houses on the side.

In 1930, Ruby Ross Wood, one of New York’s grand dame decorators, visited a stylish house that Baldwin had created. She wrote to him declaring it “a beacon of light in the boredom of the houses around it,” and invited him to come to the city to assist in her business as soon as the economy improved. He arrived five years later and worked for her until she died in 1950, absorbing all of her decorating wisdom, which he later distilled down to “’the importance of the personal, of the comfortable, and of the new.” After her death, he ran her firm for two years, before setting out on his own.

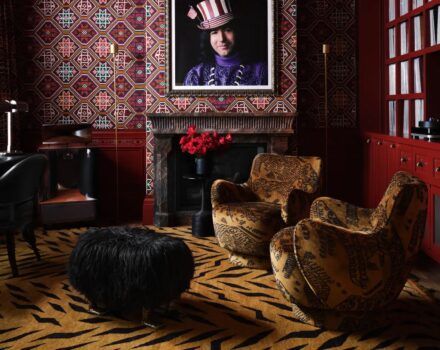

Baldwin’s own New York City apartment.

Elfin in size and always impeccably dressed, Baldwin was once described by a friend as “a small but exquisite jewel.” He lived in a surprisingly compact L-shaped studio on the East Side, which he described as “a library where I sleep.” The walls were painted a high-gloss dark brown, and were lined with his signature brass etageres, brimming with books, and floor-to-ceiling mirrors to give the illusion of space. The seating was simple, clean-lined upholstered pieces, including one of his slipper chairs, all in sharply tailored ivory cotton slipcovers.

The Baldwin-designed Manhattan home of Mr. and Mrs. Lee Eastman.

Unlike most decorators of his era, Baldwin believed that every project should feature furnishings already belonging to the client, so that the client’s personality would manifest in the room’s atmosphere. That atmosphere would emerge out of Baldwin’s selection of other furnishings — both old and new, American, European and Asian — and his choice of colors, mix of patterns and keen sense of proportion and scale. If good antiques were beyond a client’s budget, he advised buying top contemporary pieces, rather than reproductions. What was important was quality, as well as comfort. A resolute anti-snob, Baldwin detested pretentious people. He believed decorating was a collaborative adventure embarked on with the client.

Embracing of new materials, including fake leather and plastic, in the mid-1950s, Baldwin covered the walls of Cole Porter’s tony Waldorf Astoria suite in tortoise shell vinyl. For that project, possibly his masterwork, he also designed floor-to-ceiling brass étagères, as he felt it “would be extravagant to do built-in bookcases for an apartment in a hotel.” His enthusiasm for chintz slipcovers prompted Porter to threaten, “Don’t you dare slipcover these pianos!” When the hotel suite was published, the étagères began showing up everywhere. Baldwin was not pleased. “If I find that something I am doing is becoming a trend, I run from it like the plague,” he declared.

Babe Paley in her Baldwin-designed apartment in New York’s St. Regis hotel.

For the New York City apartment of William and Babe Paley in the St. Regis hotel, Baldwin covered the damaged walls in a shirred geometric fabric, which started another trend. Among other much-copied design signatures were low slipper chairs, swing arm brass lamps, dark-hued rooms, rattan-wrapped Parson’s tables and arresting orchestrations of brilliantly patterned cotton prints.

When he turned 70, Baldwin retired and a few years later decamped to Nantucket where he had often summered, and which he loved in part for its strong, clear New England light. When he died at 80, he had influenced a generation of American decorators and shaped the tastes of Americans on a mass-scale, even those who never knew his name.