For roughly 300 years, starting in the 15th century, Japanese art experienced a golden age, thanks to the Edo-based Kano school, the longest-lived and most influential school of painting in Japanese history. This group of artists and craftsmen depicted samurai society, elaborate landscapes and sacred sites on hanging scrolls, sliding doors, wall paintings and folding screens, all under the sponsorship of the ruling military, the aristocracy, the clergy and the merchant class.

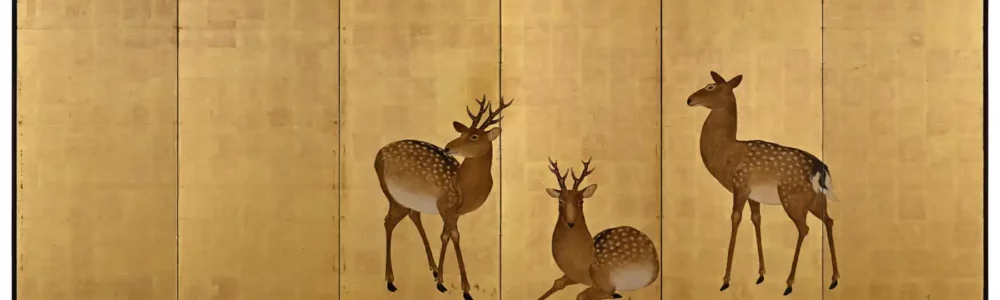

The precision seen today in Japanese arts and crafts has its roots in Kano’s rigorous organization: The branches of the school were ranked and operated like a well oiled machine, with each one serving various segments of society. At the top were the four most prestigious art families, the Okueshi, or inner court painters. Below them were the Omote-eshi, or outer court painters, followed by the Machi Kano, who catered to wealthy townspeople. One of the elite Okueshi families, the Kobikicho Kano, produced the pair of 18th-century screens featured here.

“Pieces like this were commissioned by high-ranking military officials of the Tokugawa shogunate,” says Kristan Hauge, whose eponymous gallery, in Kyoto’s museum district, specializes in antique and modern folding screens and scroll paintings and is offering these screens on 1stDibs.

They “would have been brought out and displayed in a private residence only on special occasions,” adds Hauge, “which would have included a visit by another military official or high-ranking religious figure. Afterwards, they would have been folded up and put back into storage.” During such a visit, the screens would have been placed directly behind the seated owner, to signal his allegiance to the emperor, as well as his personal wealth and power. “The rulers of this time period were the Tokugawa shogunate, and their goal was the stability and continuity of feudal society,” says Hauge, referring to the military dictatorship that governed Japan from 1603 to 1868. It was a period of relative tranquility and unity in Japan after the chaos of the violent Sengoku period that preceded it. Paintings like these were intended to communicate the continuity of rule. (Tokugawa shogunate made its capital the city of Edo, now Tokyo.)

The two screens, with their gold-leaf backgrounds, were created by the artist Tsunetake Yotei, who depicted on one a pair of frolicking peacocks and on the other a phoenix. “Peacocks were meant to convey high status, wealth and power,” Hauge explains. The mythical phoenix, meanwhile, “was a symbol of peace. The idea was that a phoenix would only appear in a kingdom blessed with prosperity during the reign of a virtuous emperor. The paulownia tree (often called a princess tree), on which the phoenix is perched, was considered sacred — together, they carried strong auspicious connotations.”