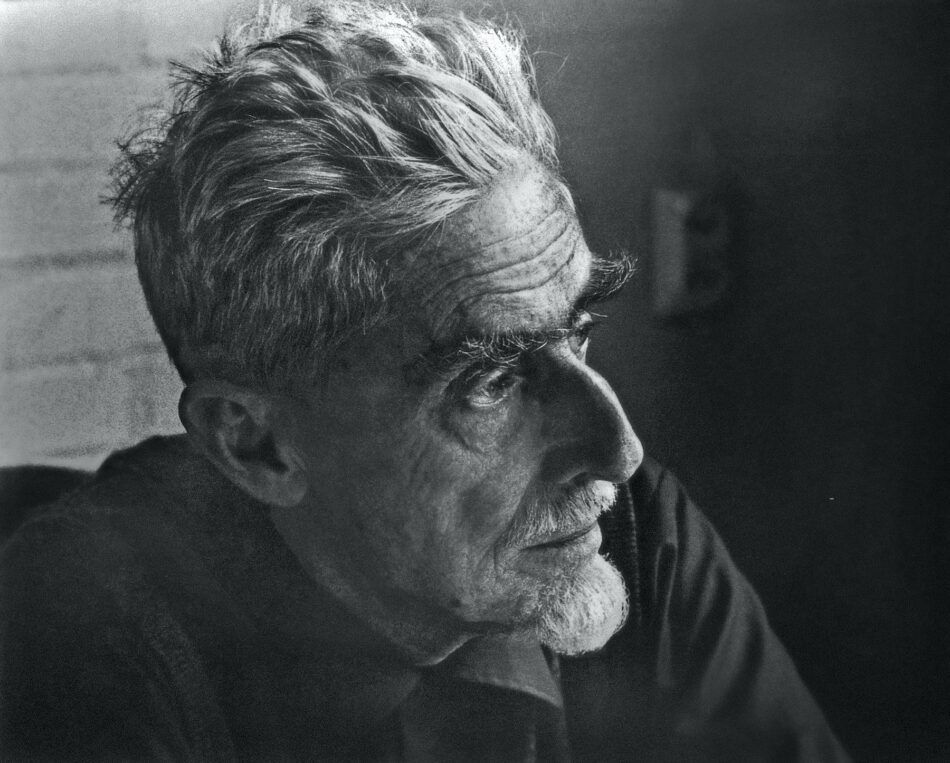

Nothing is quite what it seems in the universe of Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898–1972). The Dutch artist, famed for his graphic prints featuring infinite staircases, twisted perspectives and self-replicating animals, was a master of illusion in more ways than one. His pictures aren’t simply puzzles designed to play tricks on the brain; they were born of a desire to stretch our powers of perception, to encourage us to cultivate a natural curiosity and playfulness about the world around us.

According to New York gallerist Skot Foreman, the artist had a rare gift. “He combined the structure and analytics of the left brain with the artistic creativity of the right brain,” Foreman explains. “Somehow, he turned images into mind-bending universes that were able to stretch the boundaries of our imagination, urging us to rethink the realms of possibility within nature’s laws of order.”

But creating illusionistic illustrations was not Escher’s only talent. He was also a passionate diarist, recording his thoughts and frustrations in written form throughout his life. He often lamented that his pictures could never fully convey his cerebral imaginings.

At the same time, he expressed impatience with those who couldn’t see beyond the surface appeal of his shape-shifting patterns. Escher was an artist who sought perfection and felt misunderstood by the mainstream art world. Both traits find expression in a late diary entry reading, “I fear that there is only one person in the world who could make a really good movie about my prints: myself.”

Now, he has been given the chance to do just that — as far as is posthumously possible — by Dutch filmmaker Robin Lutz. Lutz’s M.C. Escher: Journey to Infinity, recently released in select U.S. theaters, uses the artist’s own words, read by British actor Stephen Fry, to relate his life from his upbringing in a wealthy Dutch family at the turn of the last century to his travels throughout Europe.

“The most important thing about Escher is that he was always curious, always researching and exploring. Most people lose this quality as they get older, but Escher maintained a childlike enthusiasm for the world,” says Lutz, whose thoughtful feature-length film marries documentary footage with animation and unfolds at an unhurried pace, allowing Escher’s witty and intelligent prose to gently guide us through his creative evolution.

Providing insight into the artist’s complex character are his sons Jan, aged 80, and George, 92, who share some of the charming idiosyncrasies related to their father’s inquisitive nature. We learn, for example, that he always carried a magnifying glass in his pocket to “enjoy the tiniest details” at his feet, be it a plant climbing a rock, a butterfly or a grasshopper.

We also discover that Escher had a real passion for travel and spent more than a decade in Rome with his wife, Jetta, and young family. It was there that he first played with multiple perspectives, sketching the city’s architecture at night to avoid the “excessive baroque frills” he deemed too distracting in the daylight.

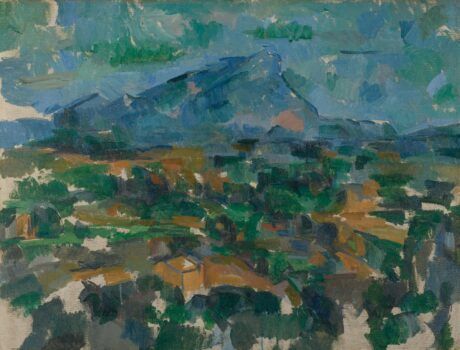

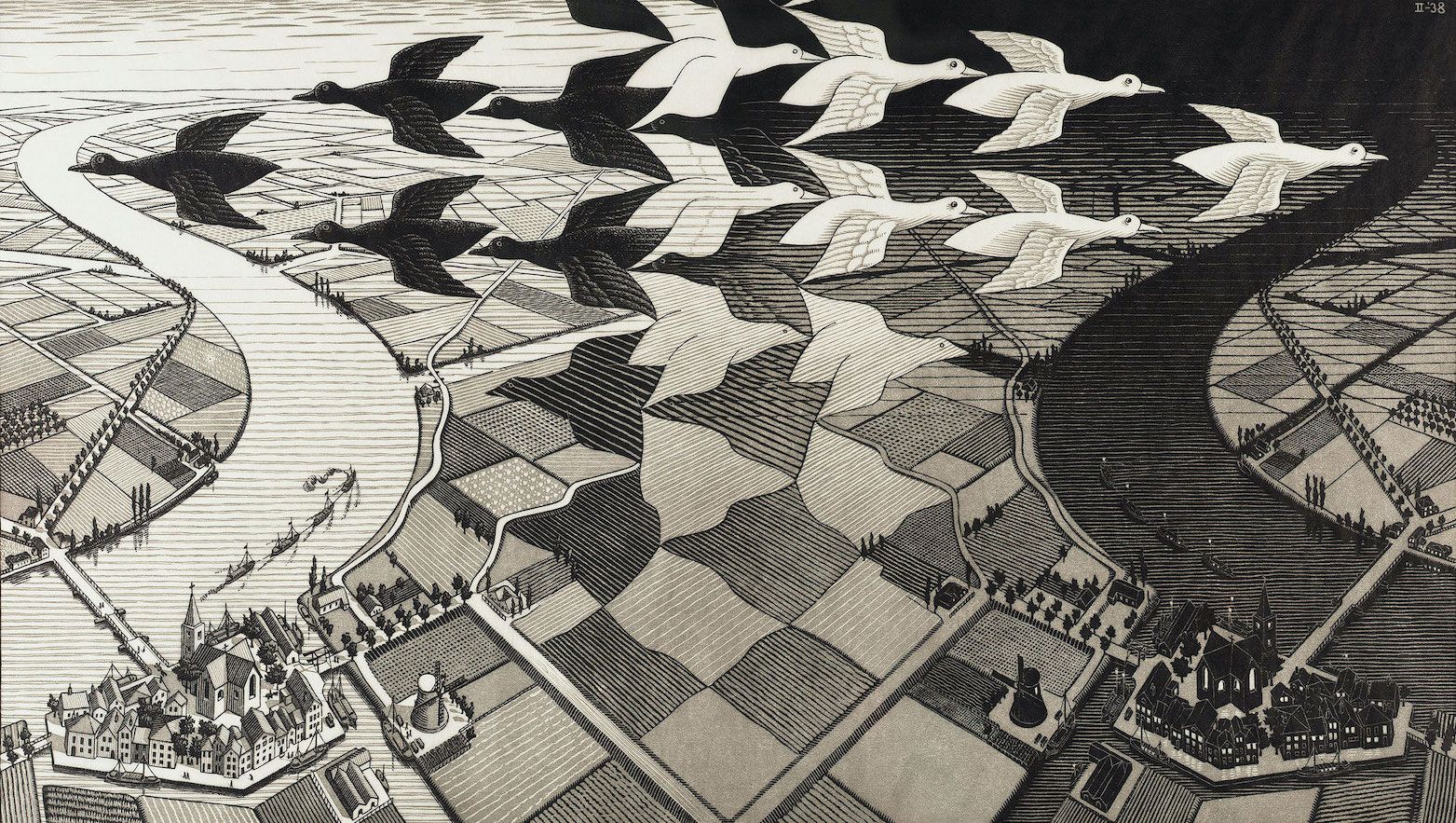

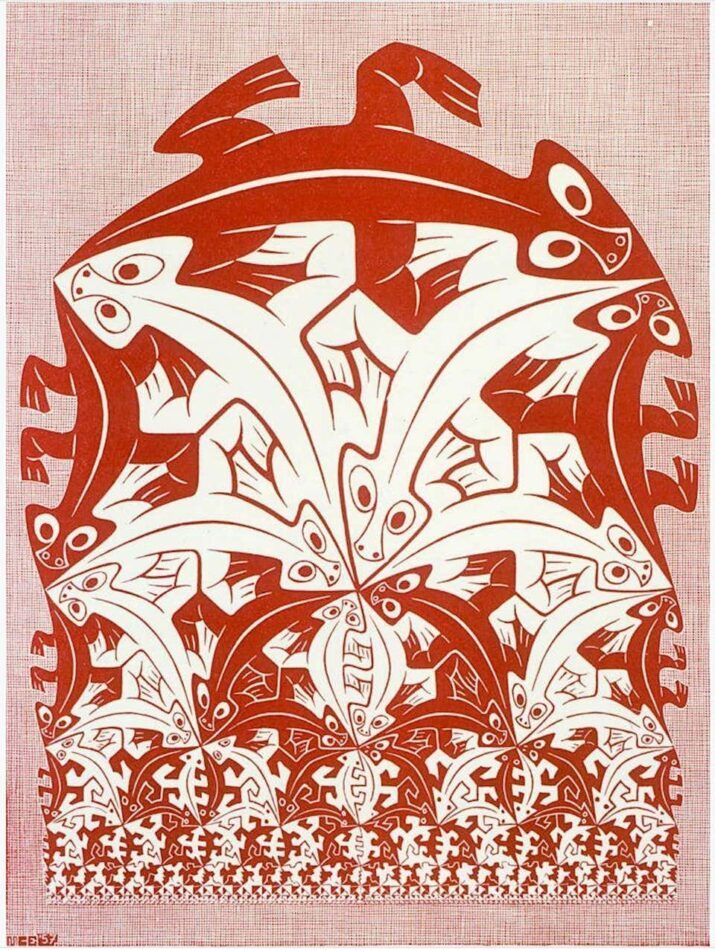

Another big development was sparked by a 1936 visit to the Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain. Inspired by the Moorish tiles of the 14th-century landmark, Escher started to experiment with repeating patterns, or tessellations, creating his first woodcuts and lithographs of metamorphosing birds, lizards and fish interlocking and filling the entire surface of the paper in jigsaw fashion.

As Escher (voiced by Fry) explains in the film, these works have a hidden symbolism, intended to illustrate the transience of life as well as the unbreakable rhythm of nature, which captivated him.

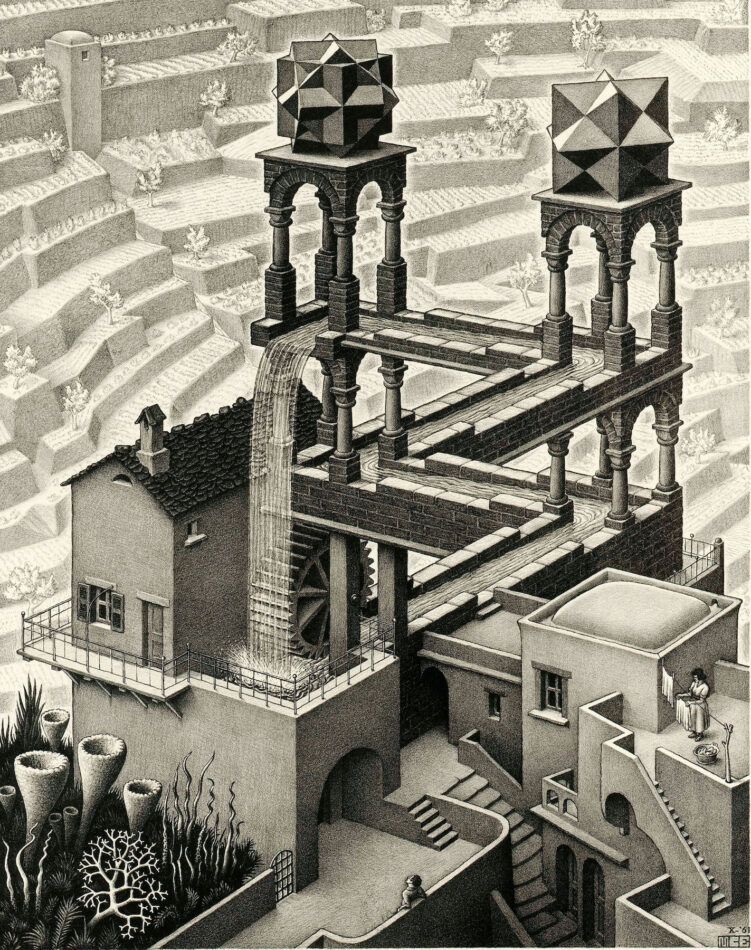

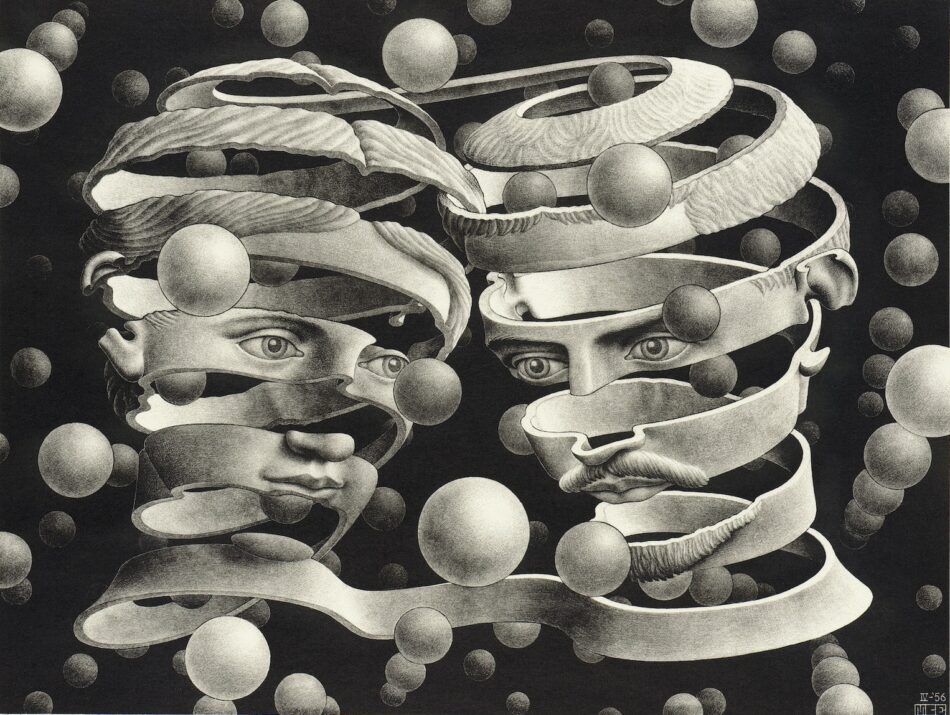

During and directly after World War II, Escher produced many of his most famous works, emotional reactions to a world plunged into chaos. This period marked the start of his fascination with impossible staircases, never-ending waterfalls and cyclical still lifes featuring figures and creatures seemingly caught in a loop, a paradox of entrapment and renewal.

“I am personally fondest of Escher’s midcareer images, executed in the latter half of the 1940s to the early ’50s, which also marked the Cold War period when the USA and the Soviet Union were engaged in the Space Race. These works have an added dimension set against an outer-space backdrop,” says dealer Foreman. “I believe this stoked Escher’s mind with even more source material and coincided with academia’s embrace of his work, which included scientists, mathematicians, crystallographers and other scholars who frequently exchanged thoughts and ideas with him.”

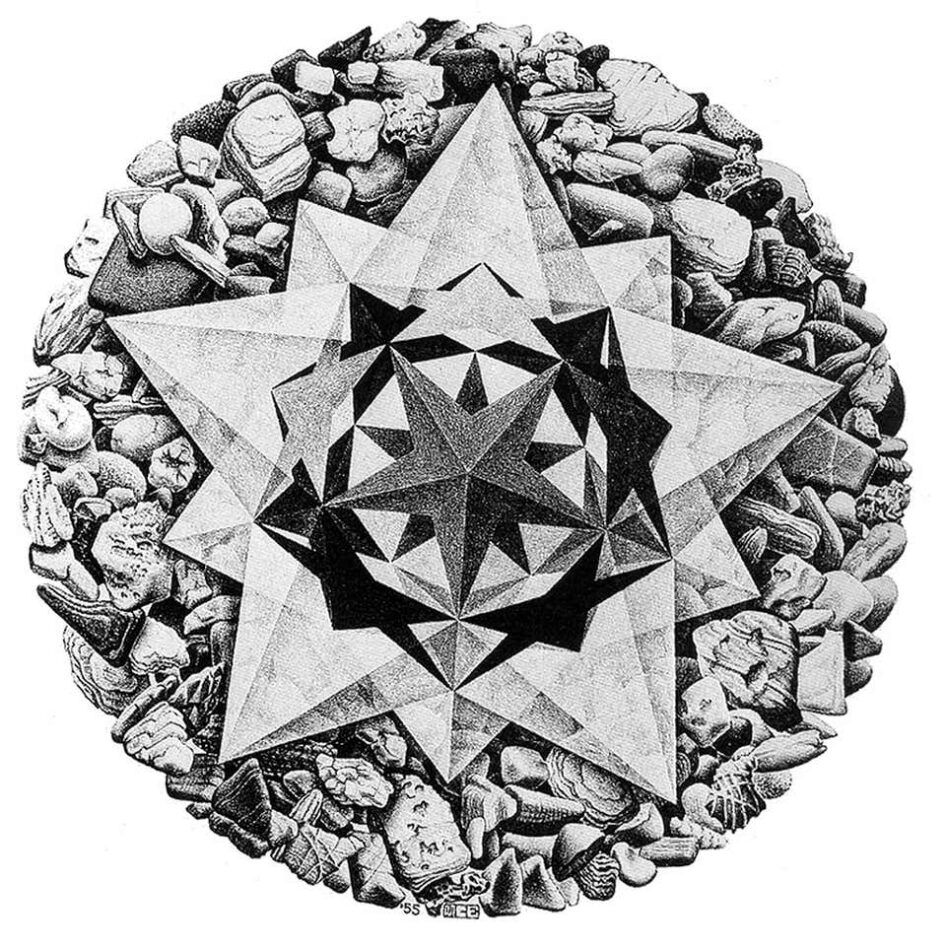

It’s true that Escher did not consider himself an artist. He preferred to call himself a mathematician, dedicated to conveying systems of order within his compositions. Escher’s famous Ascending and Descending lithograph of 1960, for example, which depicts identical monks caught on a never-ending stairway, is his interpretation of the Penrose stairs, a geometric brainteaser developed by Escher’s friend British physicist Sir Roger Penrose and his geneticist father, Lionel Penrose.

“As well as being fascinated by small things, he was also amazed about the enormity of the universe,” says art historian Marijnke de Jong, who coproduced the documentary. “In his letters, he ponders the shape of the Earth — how it is possible that this giant ball exists and contains all this life. So, he wasn’t trying to reduce or trap anything but to convey a sense of infinity, a world without limits.”

It’s no wonder, then, that Escher’s probing, mind-expanding prints have such enduring appeal. His influence has permeated all genres of artistic expression, evident in such cinematic fantasies as the Matrix and Harry Potter franchises as well as myriad video games full of surreal dreamscapes and topsy-turvy staircases recalling his distorted images.

The artist, who died in 1972 at the age of 73, might not have enjoyed all this attention. In the 1960s, he was heralded as a hero of psychedelic design by members of the hippy counterculture. Escher was quite troubled by this interpretation, maintaining that his work was not a “trippy” form of escapism but a pure and unfettered reaction to different environments.

The documentary relates his rejection of a written request from Mick Jagger to design a Rolling Stones album cover. Revealing his prickly side, Esher made his disapproval clear in his curt response to Jagger’s secretary and berated the rockstar for having taken the liberty of using his first name instead of the politer “M. C. Escher” in his correspondence.

Escher’s reluctance to engage with popular culture was in fact due less to arrogance than to his preoccupation with precision and control. He was driven by a desire to get under the surface of things, to connect with his subjects, no matter how big or small.

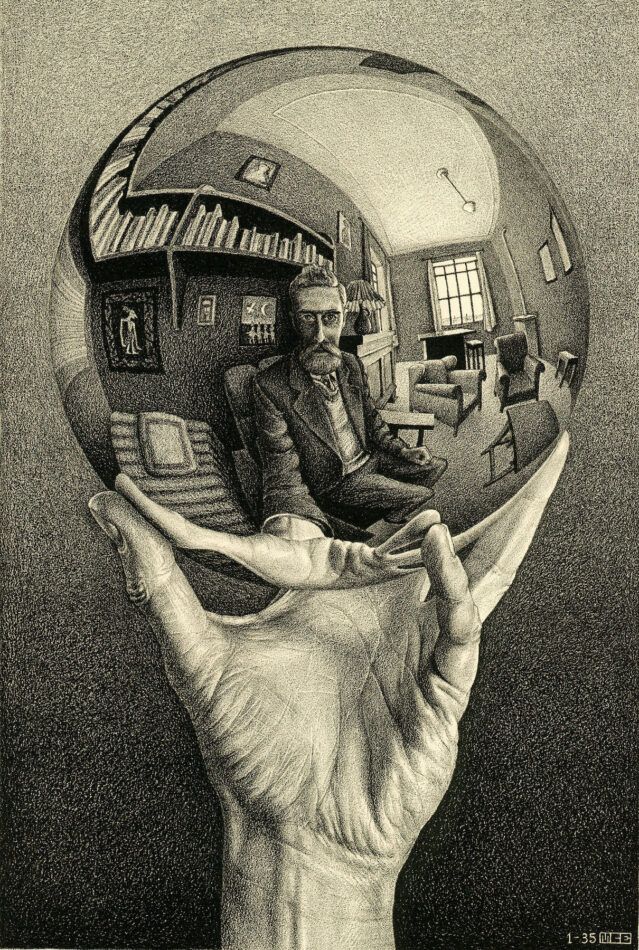

Indeed, the concept of infinity was a major inspiration for him. It informs his fish-eye studies and curvilinear perspectives, which cram in so much dizzying detail it’s impossible to know where one thing ends and another begins.

“I think Escher’s work is particularly relevant in these uncertain times, because his art was reactive,” says Lutz, who believes that the artist’s iconic prints hold a lesson for our present moment.

“At the start of the pandemic, we saw a lot of creativity,” he explains. “People were making films and animations. They were singing in the streets. Escher would have appreciated this reaction because he was so playful. Now, we find ourselves caught in a more introspective chapter of the pandemic, and we are less playful. With lockdowns all over the world, we have more time on our hands, and this can be quite daunting and challenging. We are learning to look closer at things, to be more patient and curious. This is exactly what Escher did. He didn’t follow the same pace as others. He took time into his own hands.”

Lutz’s words are echoed in those of musician and lifelong Escher fan Graham Nash, of folk-rock supergroup Crosby, Stills & Nash, who ends the documentary with this succinct but powerful conclusion: “You have an overall appreciating of an Escher piece, but when you look at it deeply, it becomes even more miraculous.” And indeed, wonders never cease in the illusory and beguiling universe of M.C. Escher.