The fabled decorating firm Maison Jansen opened its doors in Paris, in 1880. Its founder was a young Dutchman in his mid-twenties by the name of Jean-Henri Jansen. His origins are a bit of a mystery, though it’s suspected he must have apprenticed at a prestigious architecture or decorating firm, as he seems to have had an extensive network of high-level contacts from the moment he set up his business.

What’s certain is that he was an enormously talented decorator, entrepreneur and publicist because Maison Jansen quickly became a leading tastemaker and remained one for the next century. Thanks to his efforts, Jansen became the first international design firm. When he died in 1928, Maison Jansen had outposts in major cities throughout the world: London, New York, Buenos Aires, Cairo, Havana, Prague, Rome and Rio de Janeiro.

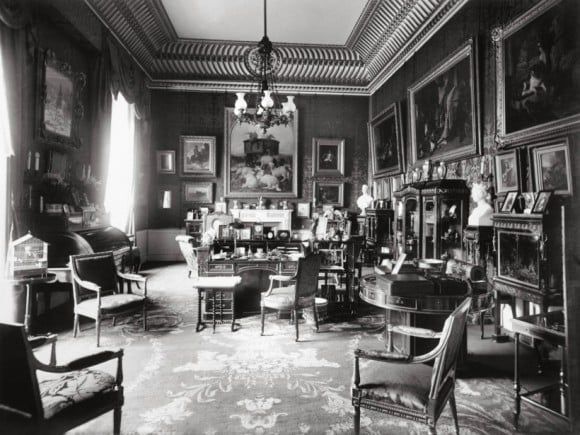

The Maison Jansen-designed private study of Edward VII at Buckingham Palace.

Maison Jansen quickly established its name by participating in some of Europe’s most influential fairs, beginning with the 1883 International Colonial Exposition in Amsterdam. Invited to exhibit in the French pavilion, the firm displayed regal Louis-style settings that played up the refined supremacy of Gallic taste, earning it a silver medal.

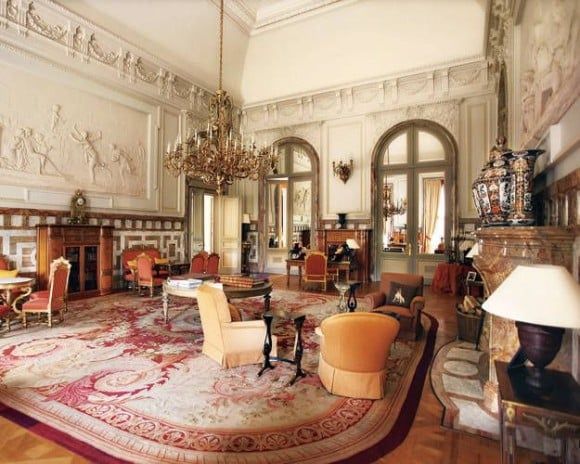

Its expertise in mixing period majesty with updated comforts became something of a calling card, opening many palace doors during its years of service. King Willem III of the Netherlands and King Alfonso XII of Spain were among Jansen’s earliest clients. Then came King Leopold II of Belgium, who commissioned the firm to decorate the new interiors of Château du Laeken, after the royal family residence had been nearly destroyed in a fire. An enormous project, it was not fully completed until the 1960s!

A sitting room in the Chateau de Laeken.

Great Britain’s King Edward VII utilized the firm’s services when he decided to update the Victorian décor at Buckingham Palace, as did King Edward VIII, although Jansen’s decorative schemes for his private rooms were never realized as he departed the palace so soon after he ascended the throne!

Egypt’s King Farouk and his family were clients, as was the Shah of Iran, who commissioned the firm to design the spectacular celebration of the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian empire, at the ancient ruins of Persepolis, in 1971. The sumptuous four-day affair took a decade to plan, but ironically, the event’s wild extravagance — it cost a rumored $50 million — fueled the revolutionary fervor against the Shah, contributing to his eventual overthrow.

The banquet tent where 60 heads of state and other glamorous guests celebrated the 2500th year of Persian empire.

Due to the elevated status of so many of its clients, Jansen’s approach to decorating was different from that of the great “lady decorators” of the early 20th century — Elsie de Wolfe, Syrie Maugham, and Sibyl Colefax — who were at times the firm’s competitors as well as collaborators.

For example, Elsie de Wolfe commissioned the Jansen decorator Stéphane Boudin to design her legendary 1938 Circus Ball, as well as the party pavilion she added to Villa Trianon, her country house outside Paris. She also received a percentage of the commissions from any clients she sent its way.

Elsie de Wolfe’s party tent at Villa Trianon by Jansen decorator Stéphane Boudin.

While the wealthy went to these women for their smart taste and vision, those who sought out the Paris-based design firm didn’t want a decorator’s stamp on their homes. “It was not proper for one to overshadow the client,” Claude Mandron, a former decorator at the firm, told James Archer Abbott, the author of Jansen (Acanthus Press, 2006).

Decorators were there to “assist,” which was why, he explained, you “rarely see a period credit assigned to a Jansen interior.” Of course, in reality, the complexity of the projects Maison Jansen handled and their sophistication were far beyond the talents, and possibly taste, of your average monarch.

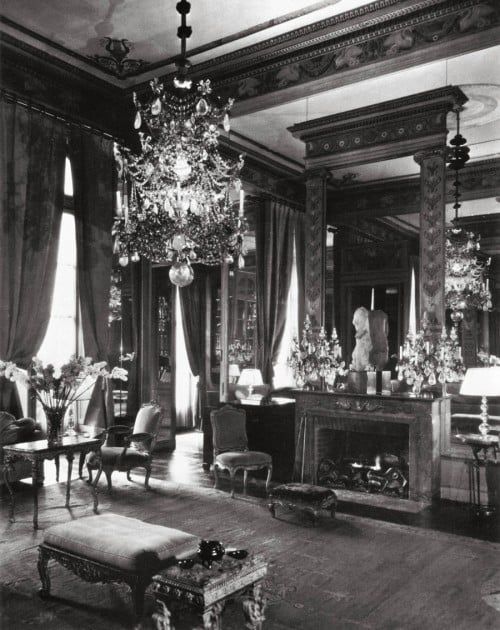

Coco Chanel lived and entertained in a glamorous Maison Jansen apartment in Paris.

To be as successful as Jansen was, the firm needed not only to be skilled in sourcing exceptional antiques with illustrious pedigrees, but also in finding superb artisans who could reproduce period furnishings to the same exacting standards as the old master ébénistes. The amount of furnishings needed to fill the immense Château de Laeken alone was beyond the available supply of top-quality antiques. By 1900, Maison Jansen was commissioning so much furniture that it established its own atelier, which at the height of its operations, employed 700 artisans.

Jansen often customized period-style pieces to suit its clients’ particular needs. For the Beaux Arts mansion of the Count and Countess de Revilla de Camargo in Havana, for example, Jansen not only made Louis XV-style furnishings from imported Cuban mahogany (tropical wood was used for all clients in equatorial climes because of its resistance to insect infestation and rot), but also designed new types of period-style furnishings like a fauteuil rocker with an airy cane back and cane-backed Rococo dining chairs.

The entry hall of the Havana residence of the Count and Countess de Revilla de Camargo.

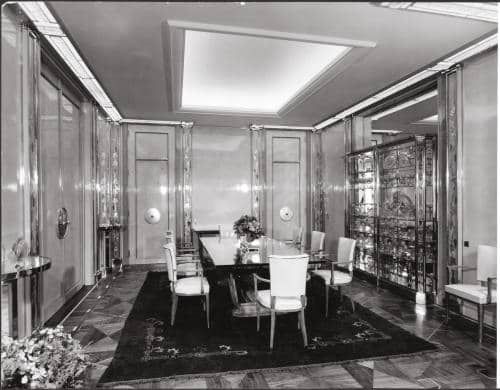

While it excelled at these reproductions and adaptations, Jansen’s artisans also produced directional designs. For the Exposition Universelle in 1900, the firm created a set of Art Nouveau furnishings and paneling that rivaled the achievements of Majorelle. Later, it became known for its Modern Regency–style designs, like mirrored coffee tables, chiffoniers, and paneling, along with gilt bronze shelves and stools with zebra-patterned upholstery.

The dining room of Chateau Solveig in Switzerland was one the firm’s most forward-looking and glamorous projects. The dining table, side tables and paneling all feature mirror veneers.

Another of its best-known — and most ingenious — designs was an elegant gun-metal wheeled dining table that could be split apart and transformed into two demilune side tables when not needed for entertaining, perfect for clients with small pied à terres. It became the Jansen Collection, high-quality production pieces the firm introduced in the 1970s. Despite efforts to address a changing marketplace and client — the firm introduced the cutting-edge designs of Garouste et Bonetti — it struggled to keep up with the changes in taste and society that the 1980s ushered in, and ultimately shuttered its doors in 1989.