Picture a woman in a print advertisement of the 1950s vacuuming her spotless living room while sporting pearls and high heels. She looks positively thrilled. It may seem silly to us now, but her delight makes sense in the context of her time.

Let’s suppose she was born in the first decades of the 20th century. She could remember her mother or grandmother shoveling coal into a cast-iron kitchen stove, boiling water for a bath, doing laundry by hand and making every meal from scratch, forever worried that ingredients would go bad without a reliable way to cool them.

Now, imagine her experiencing the marvels of postwar middle-class life — refrigeration, a dishwasher, a washer-dryer and a programmable oven, to say nothing of a streamlined vacuum cleaner — which shaved hours off domestic chores and transformed drudgery into a close encounter with high technology.

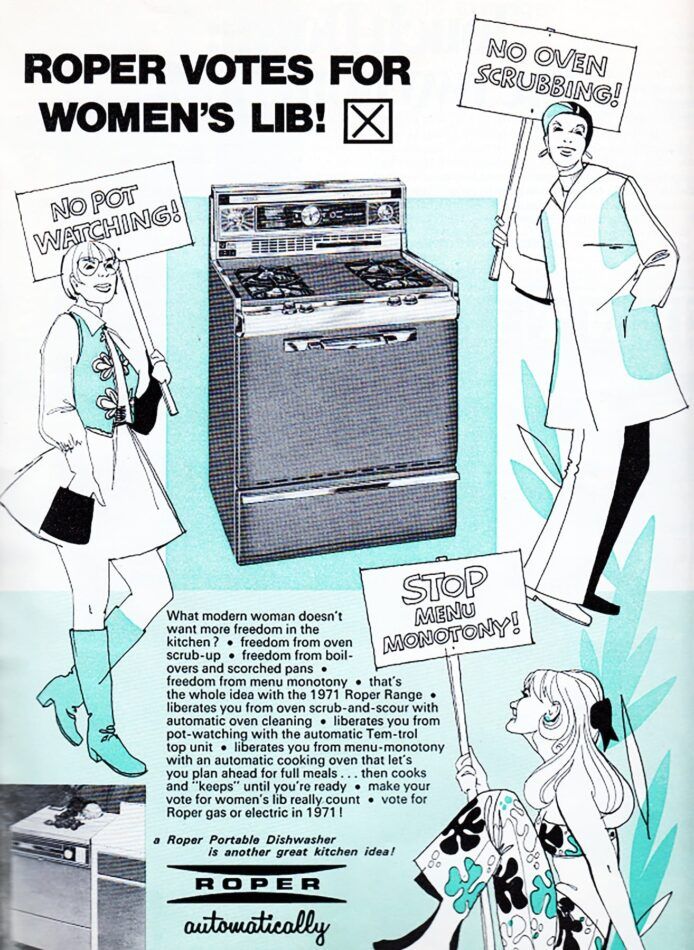

Without question, the innovations of the fully equipped postwar kitchen contributed to women’s emancipation in the 20th century, even if they weren’t initially sold that way.

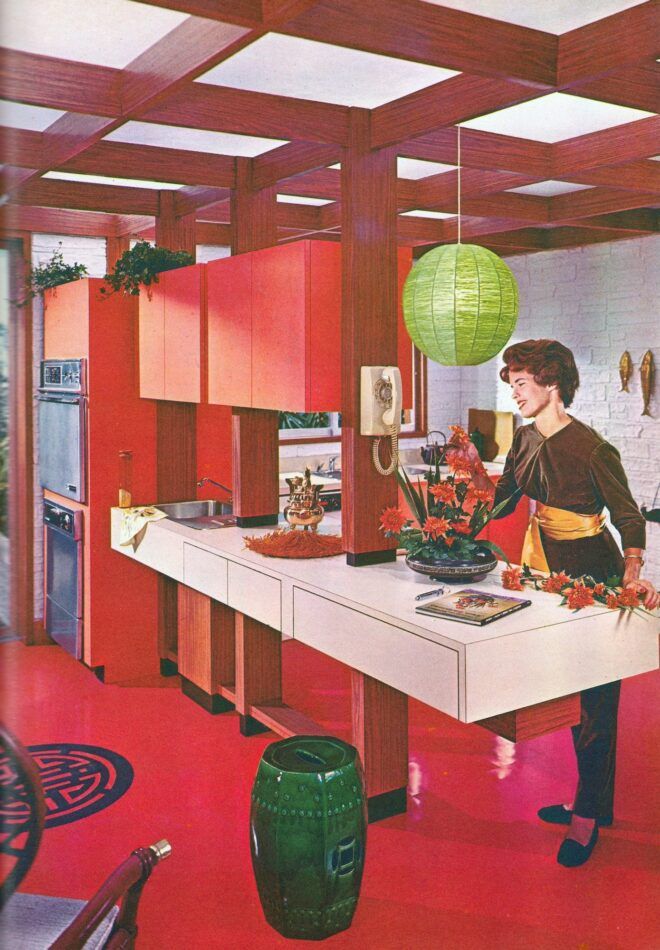

The mid-century kitchen, particularly before the women’s movement gained traction, embodied a paradox: Appliances had the look and feel of machines symbolizing seemingly limitless technological progress, like streamlined trains and colorful cars, yet women’s progress lagged behind.

Today, ironically, both the world and women’s lives have changed, but the technological and design ideals of the postwar kitchen are alive and well. Almost every aspect of the modern kitchen, from tools and appliances to cabinets, storage and work surfaces — with the exception of the microwave oven — adheres to the middle-class standard set seven decades ago.

By contrast, for Americans living in the 1950s, the kitchen of seven decades earlier — the 1880s — would have seemed practically medieval. Appliances have undergone cosmetic changes and become much more energy efficient, but in most other ways, the mid-century kitchen has not been improved upon. And why should it be? For millions of homeowners back then, the postwar kitchen was a hard-earned dream come true.

I tried to distill this chapter in culinary design history in my book The Midcentury Kitchen: America’s Favorite Room, from Workspace to Dreamscape. 1940s–1970s (Countryman Press). Here is a tour of some of the most indelible and influential kitchen designs I found while researching this fascinating topic.

Whirlpool Miracle Kitchen

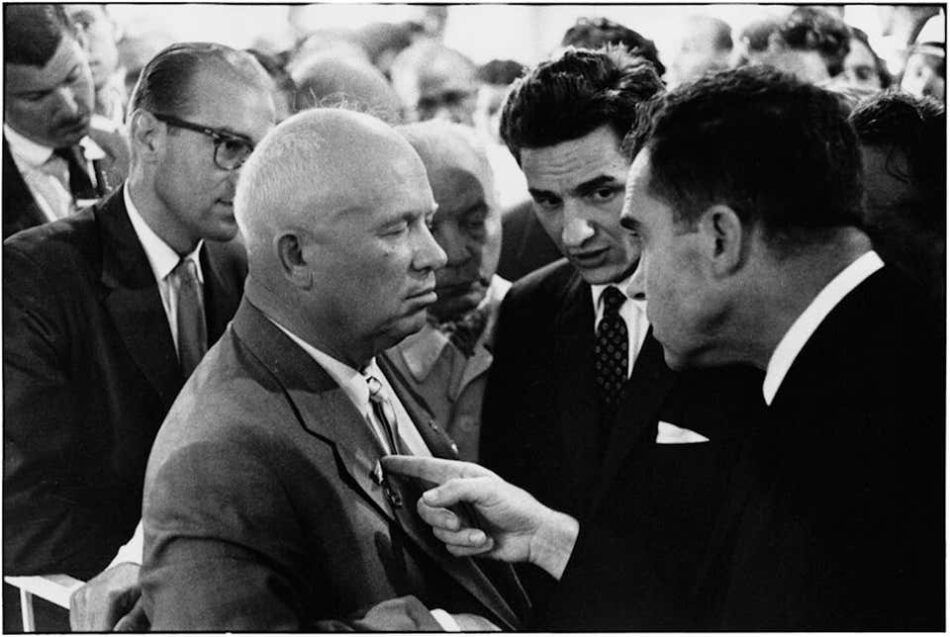

On July 24, 1959, then–Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev got into an argument about women, kitchen appliances and the American way of life. It wasn’t planned. But it was recorded on film and broadcast in both nations.

It was also the first high-level meeting between American and Soviet leaders since the 1955 Geneva Summit. In 1958, the two countries had agreed to a major cultural-exchange project: The USSR would organize a World’s Fair–style exhibition in New York City, and the United States would do the same in Moscow.

So, Nixon traveled to the USSR tasked with giving Khrushchev a tour of the American National Exhibition in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park. The two leaders had several conversations over the course of the tour, but the most iconic of these occurred while they were standing with a crowd in front of a model American kitchen.

It had all the modern conveniences you’d expect to find in the sort of new postwar home that would sell for $14,000 (about $120,000 today): stylish cabinets, a dishwasher, a range and a refrigerator. Khrushchev was cantankerous, waving his hand dismissively while declaring (through a translator) that the innovations in the American model kitchen were gadgets of little consequence. He then asked if there was a machine that “puts food into the mouth and pushes it down.”

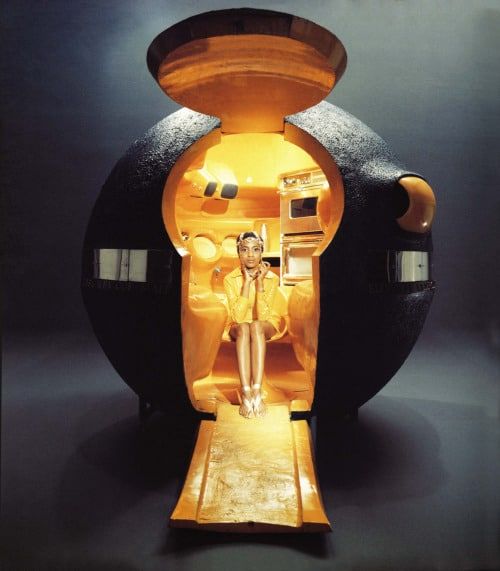

If Soviet visitors to the fair were moderately impressed by the middlebrow gadgets in the model kitchen, they were wowed by the aptly named Miracle Kitchen, a joint venture between Whirlpool and RCA, first designed in 1956. The Miracle Kitchen traveled across the U.S. throughout 1957, then went on display in Moscow in 1959.

It was introduced to Soviet visitors at the American National Exhibition by a young woman named Anne Anderson, who was born in Illinois to Ukrainian parents and spoke fluent Russian. Photographer Robert Lerner took portraits of Anderson demonstrating devices and posing with appliances in the Miracle Kitchen for LOOK magazine, which ran a feature on it in July 1959.

Anderson looked as though she herself had been styled to coordinate with the kitchen’s brightly colored Formica panels. She wore a pale-blue shirtwaist dress, bright red lipstick and a red manicure; strands of pearls and a pair of black high heels completed the effect. She was wearing the mid-century uniform of a woman who keeps house on her own but also commands a small army of machines to lighten her workload.

The kitchen had been designed to intimidate Soviet visitors, and to engender in them a feeling of being have-nots, even as their government maintained an edge in the early years of the Space Race. But the Miracle Kitchen was a kind of appliance fantasia, more aspirational than realistic, even for wealthy Americans of the era.

It featured a compact vacuuming robot. The freestanding range could (theoretically) bake a cake in three minutes, using microwave technology. The dishwasher would slide on a track over to the dining table after meals for easy loading. Anderson demonstrated the kitchen’s push-button “planning center,” from which she could summon the dishwasher or the mini-vacuum cleaner.

If all of this sounds too good to be true, it mostly was: According to a 2015 interview with one of the kitchens’ designers, Joe Maxwell, who had worked with the Detroit-based design firm Sundberg-Ferar, a two-way mirror installed in the kitchen display allowed someone behind the scenes to move the vacuum cleaner and the dishwasher back and forth by radio control.

Perhaps some Soviet visitors believed this display represented a typical middle-class kitchen in the United States, but the closest we came during this period to a kitchen “miracle” was in Hollywood.

Car Culture

In the mid-1950s, General Motors hired a group of women it nicknamed the Damsels of Design. Harley J. Earl, at the time the vice president of the company’s styling section, began discreetly employing these female industrial designers in the 1940s, because he believed they could help GM better understand women’s preferences — namely, how they shopped and made major purchasing decisions.

Earl recruited most of the “damsels” from the Pratt Institute, in New York, and GM publicized the hires widely. Dozens of color photographs show the women posing with clay models of concept cars in progress or showing off the features of new models. Six of the women — Ruth Glennie, Jeanette Linder, Sandra Longyear, Marjorie Ford Pohlman, Peggy Sauer and Suzanne Vanderbilt — were assigned to the automotive interior-design department on aspects of decor, with the exception of the dashboard.

The other four — Dagmar Arnold, Gere Kavanaugh, Jan Krebs and Jayne Van Alstyne — worked at Frigidaire, where they were part of the team that designed the Kitchen of Tomorrow. Earl organized an event called the Feminine Auto Show in GM’s Styling Dome in 1958 to show off their innovations, which included things like makeup mirrors, storage consoles, child-proof locks and retractable seat belts.

In the end, the “damsels” didn’t last long, but the association between cars and kitchen design, improbable though it may seem today, was deeply rooted both at GM and in the corporate design world at large. Appliance designers had tapped the aesthetics of trains and cars in the 1930s, as in Raymond Loewy and Norman Bel Geddes’s streamlined appliances or Henry Dreyfuss’s Hoover 150 vacuum cleaner.

With the emergence of color as a marketing tool in the postwar years, appliance makers borrowed something else from the car industry: the practice of annual styling. Alfred P. Sloan, president, chairman and later CEO of General Motors during the 1930s–50s, pioneered this concept in car design, inspired by the logic of planned obsolescence.

Colorful Laminates

Of all the innovations that brought color into the kitchen, the most iconic might be Formica. Like Pyrex, Formica has been around for over 100 years, but it has an especially strong association with mid-century kitchens. It was a very early plastic invention, developed in 1912 by Westinghouse as a substitute for mica, which was used for electrical insulation, and that’s where it’s name came from: “for-mica.”

In 1927, the Formica Insulation Company, as it was then called, patented a process for printing marble or wood-grained surfaces on the laminate using a process called photogravure.

During World War II, the company produced airplane propellers and bomb components that were made from a material it called Pregwood, wood that had been impregnated with plastic. American Cyanamid acquired the Formica Corporation in 1956, and by 1970, the company was focusing primarily on decorative laminates.

One of the best-preserved examples of a laminate kitchen can be found in Temple, Texas: the Ralph Sr. and Sunny Wilson House. And it doesn’t contain any Formica; it’s decorated throughout with Wilsonart High Pressure Laminates. Ralph Wilson Sr. founded Wilsonart (initially called Ralph Wilson Plastics) in 1959, and his company competed with Formica.

He designed the house with his daughter Bonnie McIninch, and it’s a veritable laminate wonderland; every conceivable surface was turned into a canvas for laminate. Wilson actually lived there from 1959 through ’72, but he also wanted the house to serve as a model for how his laminates could be used.

The kitchen in particular is a masterpiece. There, you’ll find colorful laminate-clad cabinets, as well as countertops that are a very early example of a technique called “post-forming,” in which a laminate surface is wrapped around a rounded edge. The house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.

Earth Tones

By the late 1960s, the gender roles that had assigned control of the kitchen to women in the 1950s were being turned upside down, as record numbers of women began entering the workforce and men began doing more cooking and housework than ever before.

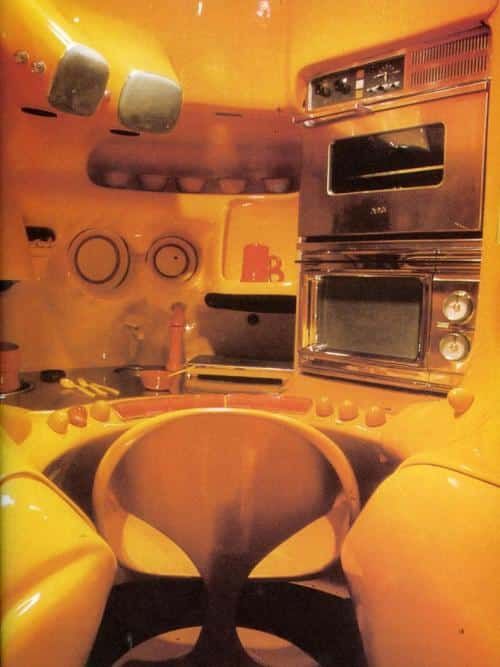

The look and feel of the hippie counterculture conquered the American kitchen, as earth-toned tile, macramé plant holders, avocado-green and harvest-gold appliances and psychedelic foil wallpaper began appearing regularly in the pages of the top shelter magazines.

Ultra-mod kitchens like the orange-and-faux-wood family nerve center on The Brady Bunch cemented this aesthetic in the popular imagination. As it turned out, the kitchen of “the future” was a more egalitarian place: fun, colorful and festive.

If anything, during this period kitchens took a stylistic turn in favor of all things low-tech. Steel gave way to wood, and appliance colors shifted away from cool pink and blue toward warm avocado green and harvest gold.

Exposed brick and deep reddish paint colors were out in force. Just as the Laura Ashley–inspired prairie fashions of the era looked back to nature, new kitchens appeared warm and lived-in rather than high-tech and brand new.

And as shades of beige and brown were conquering kitchen walls, so too were they popping up in cookbooks and on American dinner plates. The food revolution of the 1970s was fueled by concern for the environment, for health and for workers’ and farmers’ rights.

Hippies had rejected the commercial food industry in favor of “whole” foods — like brown rice, whole wheat bread and fresh produce — and little to no meat. Farming was integral to rural communes, whose members wanted to disconnect from the “grid” of the industrial food system.

From 1968 to 1972, The Whole Earth Catalog offered information about organic farming and environmentally friendly living. In 1971, Frances Moore Lappé’s Diet for a Small Planet, which advocated vegetarianism and a more progressive national food policy, hit the best-seller list.

By 1973, the year of the oil embargo, an awareness of the connections between the health of the planet, the food we eat and how we shop was becoming mainstream in the American consciousness.

Most Americans weren’t vegetarian, didn’t eat organic food and didn’t own a copy of Lappé’s nutrition manifesto. But the aesthetics of these movements, which echoed the colors and textures of the natural world, boldly made their way into American kitchens.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a time when civil unrest and social change touched every member of American society. The kitchen, then, became a canvas for working out some of those ideas.

What should we eat? How should we cook it? Who should do the cooking and cleaning? Male and female, adult and kid, futuristic and low-tech, Technicolor and natural, all of these dualities left their mark on the most important room in the house.

This text was excerpted and edited with permission from The Midcentury Kitchen (Countryman Press) by Sarah Archer.