A fine-art photograph can be visually striking. It’s also a way to display something that’s deeply personal, making a room an expression of your unique taste and style, a place that feels like your own.

While some buyers may be searching for eye-catching pieces to fill an empty wall, others might be interested in building a collection, as a passion project, an investment or to support the arts or the work of an up-and-coming artist.

It’s easy to start. You can get your feet wet with a single statement image that transforms a space or a group of smaller prints used to create a gallery wall. Collecting can be an enjoyable experience as you refine your eye and develop your taste, whether it’s for travel-themed landscapes, avant-garde fashion photos or quiet still lifes.

This guide outlines the basics of buying fine-art photography, including what to look for in a print, the artists who are considered touchstones in the field and where to begin.

What Is Fine-Art Photography?

Fine-art photography is defined less by subject matter than by intention. While a commercial or documentary photograph is made to fulfill a practical purpose — such as advertising a product, conveying information or bearing witness to a moment in history — a fine-art photograph is created as an artwork in its own right. At its heart, it’s about expression. It evokes feeling, communicates ideas or simply captures beauty in a way that resonates personally.

The defining feature of fine-art photography is that it embodies the artist’s vision rather than serving an external function.

What to Look for When Buying Fine-Art Photography Prints

When you’re considering a photograph for purchase, bear in mind a few key aspects that determine its appeal and its value.

Genre

Photographs can be grouped into several categories, or genres, which often overlap. Choosing among them is generally a matter of personal taste. Here are a few of the most common:

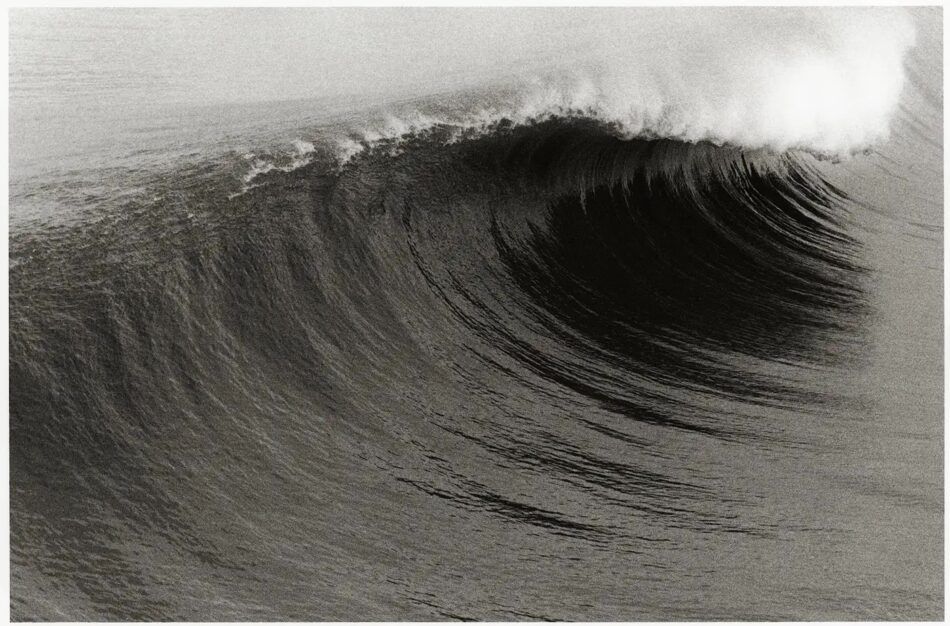

- Black-and-White — High-contrast and graphic, black-and-white images have a minimalist feel. They emphasize form, tone and texture and hark back to the early days of photography, before the advent of color film.

- Color — Color brings another dimension to photographs, adding visual pop, as well as layers of symbolism, emotion and energy.

- Figurative — Figurative photos have identifiable subjects, like people or landscapes.

- Abstract — Because abstract works don’t contain recognizable forms, they’re often more experimental and push the boundaries of the medium.

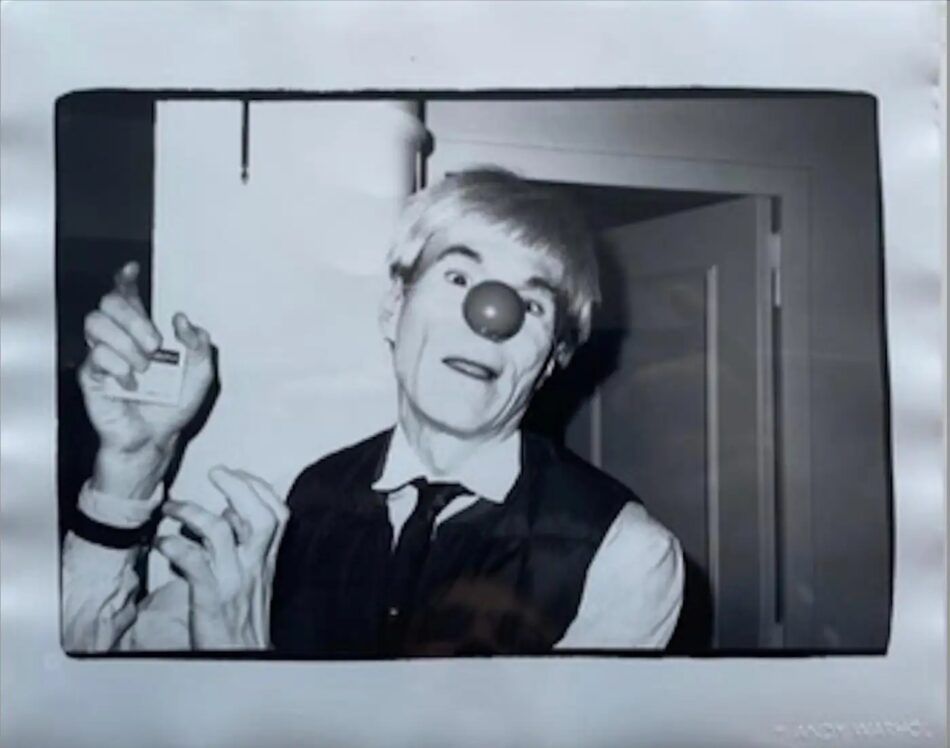

- Portrait — Photos of people (or animals) are studies in personality and provide a sense of intimacy.

- Landscape — Capturing scenic vistas, landscape photography has a timelessness and can bring a bit of nature indoors.

- Still Life — Portraying arrangements of inanimate objects, still lifes recall the formality of Old Master paintings.

- Fashion — Though usually created for commercial purposes, fashion photography can be tremendously creative, with plenty of drama and flair.

- Street — Street photography captures the fleeting moments and dynamism of day-to-day public life.

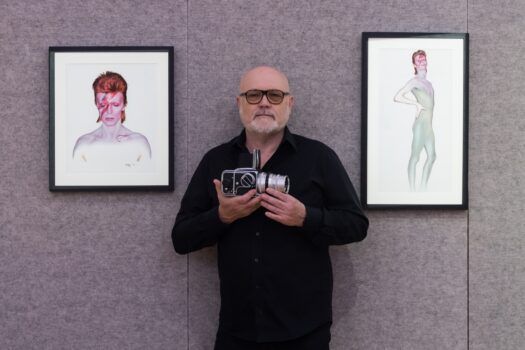

Artist Reputation

Artist reputation influences both current price and, potentially, sustained value over the long term. Established photographers, especially those represented in museum collections or with strong auction histories, typically command higher prices. Emerging photographers, however, often produce equally compelling work at more accessible entry points. Supporting them can be a meaningful way to shape a collection while engaging with new voices in the medium. Many collectors combine both established and emerging artists to balance their acquisitions.

Scale

Size dramatically affects a print’s presence. A large photograph can dominate a wall and serve as a focal point, while smaller images can encourage close-up engagement.

Think not only about the dimensions of your space but also about the role you want the photograph to play. Large-scale works may suit expansive rooms with high ceilings, while smaller prints can be grouped in salon-style arrangements or placed in more intimate settings.

Printing Process

One of the most important aspects of buying a photograph is understanding how it was made. Each process produces its own look, and the differences, though often subtle, can be significant when you’re considering a purchase.

- Gelatin Silver Print — For black-and-white works, the classic process is gelatin silver printing. The resulting photographs, developed in a darkroom from film negatives, are prized for their luminous tonal range and their sense of depth. The process is often associated with masters like Ansel Adams, whose meticulous technique demonstrated how striking a silver print can be.

- Chromogenic Print/C-Print — Color photographs are often produced as chromogenic prints, or C-prints, created by a chemical process that emerged in the mid-20th century as the standard for color photography. Collectors value them for their smooth gradations and rich, naturalistic hues. Today, you may also encounter digital C-prints, which begin with a digital file but are exposed onto light-sensitive paper using lasers. These retain the depth of traditional darkroom color while incorporating the precision of digital technology.

- Giclée Print/Inkjet Print — Other processes have developed alongside the mainstays mentioned above. Inkjet prints, often referred to as giclée prints when produced at archival quality, use pigment-based inks sprayed directly onto paper. They enable printing on a range of surfaces, from matte to glossy, and when produced to professional standards, offer excellent permanence. Collectors are increasingly comfortable with them, especially given their adaptability to contemporary practice.

- Photogram — Among the more experimental approaches, a photogram is made without a camera. Instead, objects are placed directly onto light-sensitive paper, which is then exposed to light. The result is often abstract and unpredictable, with ghostly outlines and silhouettes. These works highlight the material possibilities of photography.

When considering a print, knowing the process that produced it not only helps you understand its visual character but also places it in the context of the artist’s practice. A digital C-print by a contemporary photographer reflects different intentions than a gelatin silver print from the mid-20th century. Recognizing those distinctions enhances the experience of collecting and ensures that you know exactly what you are bringing into your home.

Editions and Authentication

Most fine-art photographs are sold in limited editions, which restrict the number of prints made and enhance scarcity. A print labeled 4/10, for example, is the fourth of an edition of 10. Photos from open editions, which have no limit, are usually more affordable but less rare. Artist’s proofs are prints made outside the edition, traditionally retained by the photographer. Signed prints provide an additional mark of authenticity and can strengthen provenance. These details are important in determining value and collectibility.

Condition

When evaluating a photograph, condition is just as important as the subject or edition. Because works on paper are inherently delicate, it’s worth taking a close look at the surface of a print for any signs of fading, discoloration or damage. Minor flaws like a small crease or slight yellowing may not be visible from a distance, but they can affect both the aesthetic impact and the long-term value. Reputable galleries and auction houses will disclose any issues up front. It’s always smart, however, to ask questions before you buy.

How to Care for Fine-Art Photography

Preservation

Once you own a photograph, preservation becomes part of collecting. Light, temperature and humidity all play roles in how a print ages.

Direct sunlight is particularly harmful, as it can cause fading, even in modern pigment-based prints. Museums often use UV-filtering glazing — special glass or acrylic that blocks damaging rays — to protect works on display, and collectors can do the same at home.

Climate control matters, too. Fluctuations in temperature and humidity can warp paper or encourage mold, so keeping art in a stable environment is ideal.

Collectors who handle larger or more valuable works often consult professional conservators, particularly if restoration is needed. Even something as simple as cleaning the glazing should be done with care, since using the wrong materials can lead to scratches or residue.

And although it may feel unnecessary at first, insurance — whether for a single photo or a growing portfolio — provides peace of mind regarding loss or damage.

Framing

Framing is as much a conservation measure as an aesthetic one. Acid-free mats and backing boards help prevent discoloration, while archival tape or corners keep the print in place without introducing standard adhesives that might cause damage. If you buy an unframed print, consider having it professionally framed using archival materials, even if you don’t plan to hang it right away.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I start collecting fine-art photography prints?

Photography is one of the easiest entry points into collecting art. Buying a print begins with determining one’s particular goals. Some buyers are looking for great works that complement their homes. Some are interested in building a collection around a theme, whether a particular genre or a favorite artist. And some collect with investment in mind.

Budget is the next consideration. Photography is available across a wide price spectrum, from affordable prints by emerging photographers to high-value works by established figures. Knowing what you’re willing to spend helps focus your search and reduces the likelihood of impulse purchases.

You can gain confidence in collecting by simply browsing photography whenever you have the chance. Visiting galleries and museums, attending photography fairs and exploring reputable online platforms are all great ways to see a range of works. The more photography you experience, the better you’re able to identify your preferences. Don’t hesitate to ask gallerists questions about edition sizes, processes and provenance. Many are happy to share their expertise.

Research is also helpful. Learning about print processes, artist reputations and editioning will help you make informed decisions.

Finally, take your time. The most satisfying collections are built around genuine engagement with the works and come together gradually, reflecting not only an eye for quality but also the collector’s evolving tastes.

Who are some well-known fine-art photographers?

Several names recur across collections and exhibitions and are considered standouts in the field. Together, these artists provide a framework for understanding the diversity of fine-art photography and its evolution.

Ansel Adams (1902–84) became synonymous with black-and-white landscapes of the American West. His images of Yosemite and other national parks combine technical precision with an abstract sensibility and remain benchmarks of fine-art photography.

Slim Aarons (1916–2006) is celebrated for his color-saturated images of high society in the mid-20th century. His photographs of poolside leisure and glamorous resorts capture the era’s ideals of elegance and luxury.

Diane Arbus (1923–71) trained her lens on those on the margins of society, producing portraits that are unflinching and empathetic. Her images challenged traditional ideas of appropriate subject matter and remain highly influential.

Irving Penn (1917–2009) produced refined portraits and still lifes defined by clarity and simplicity. His fashion photography and studio work (especially for Vogue magazine) remain among the most elegant examples of the medium.

Annie Leibovitz (b. 1949) is known for bold, narrative-driven celebrity portraits. Her work is often cinematic, with elaborate staging and a strong sense of storytelling.

Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1953) uses photography to examine race, gender and history, often combining staged images with text. Her “Kitchen Table” series and other projects are both personal and political, placing lived experience at the center of art.

Cindy Sherman (b. 1954) revolutionized the medium through her conceptual self-portraits, in which she assumes a wide range of personas. Her work explores identity, media representation and the constructed nature of images.

Mickalene Thomas (b. 1971) creates vibrant, layered portraits that celebrate Black women and cultural identity. Her work often combines photography with collage and painting, expanding the medium into new territory.

Ultimately, photography is about connection. Each photograph embodies an artist’s vision and a moment in time. By choosing to live with it, you bring that vision into your own life. A collection of photographs, then, becomes a reflection not only of the artists who made them but also of your own perspective.