The dance floor of Studio 54. Photo courtesy of Bromley Caldari

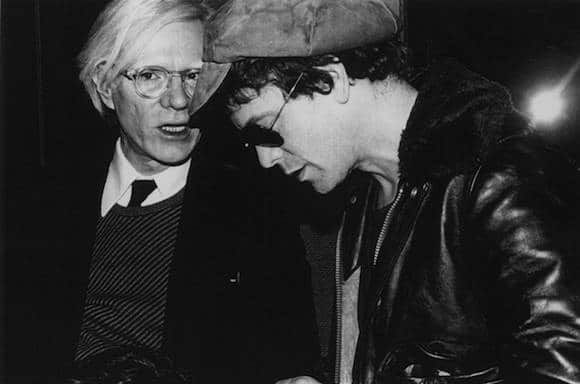

Three decades after Studio 54 opened in 1977, cofounder Ian Schrager told New York magazine that he regretted inventing the “velvet rope” barricade with his partner, Steve Rubell. “I’m surprised, quite frankly, that in 30 years no one’s come up with something better,” Schrager said. Now, 40 years out, it’s abundantly clear that some of the most enduring designs from the late ’70s are social constructs: what it means to be a celebrity, what it means to throw a party and what it means — in the words of scene-maker Andy Warhol — to have one’s 15 minutes.

Nevertheless, certain aesthetic trends persist. So we talked with Studio 54 architect Scott Bromley about the good, the bad and the groovy of 1970s design.

Studio 54 opened its doors on “April 26th, 1977, honey,” says Bromley, like it was yesterday. The club sparked immediate buzz. Cher made an appearance in suspenders and a straw hat, photographed for the cover of the New York Post, and eventually there were fables, like the one about Bianca Jagger riding in on a horse (fact check: she simply mounted it.)

Bromley’s involvement had started with a phone call from Peruvian public-relations manager Carmen D’Alessio, known for her social roster of “everyone beautiful, young and loaded,” according to Warhol. The gist of D’Alessio’s pitch to Bromley was “I represent these kids with a little disco looking at a property on 54th Street.” When Bromley went to see the former theater, Schrager and Rubell weren’t there, but he immediately had a vision that would capture the pulse of the time. “I said, ‘Everyone wants to be on the stage, let’s make the stage the dance floor,’” he remembers.

The Studio 54 balcony looked on the dance floor like a stage. Photo courtesy of Bromley Caldari

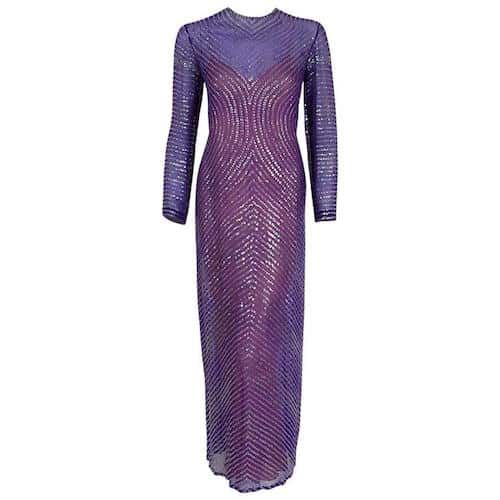

These days, Bromley interacts with a lot of young designers and architects through his firm, Bromley Caldari. “The kids are so crazy about the ’70s,” he says. But age and wisdom have brought much-needed perspective as to what should stay in the past: “Polyester 100 percent should never be again.” Instead, if you’re looking for a way to pay tribute to 1977, it would be better to go with a sequined chiffon gown by Studio 54 regular Halston.

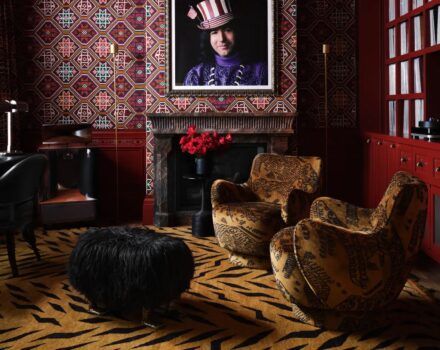

Bromley also offers a humorous critique of the elevated platforms some designers incorporated into their interiors (and the inverse: plush conversation pits.) “If you have a cocktail, it could kill you. That’s a dangerous design,” he declares. This extends to shag carpeting: “It’s not good for your knees, but before age 30 it’s terrific.” A 1977 sofa by Annie Hiéronimus for Cinna embodies some of the “intimacy” of a conversation pit, minus the literal pitfalls.

Bromley is still a fan of animal print, and uses it in his commissions — as long as it doesn’t run afoul of PETA. “I don’t want the Canadian lynx to be eliminated,” says the native Canadian (Bromley graduated from McGill University in Montreal, and gave up a spot on Canadian Olympic swim team in order to pursue architecture under the mentorship of Philip Johnson.)

For Bromley, it’s very easy to understand the intense nostalgia that 1977 evokes, even among those who were too young or too unborn to remember it. “In 1974, there was this mini economic crash, but as the decade progressed people started to loosen up. The end of the decade was joyous,” Bromley says. He adds that the ’70s had the most danceable music: “It made you feel like you were flying.”

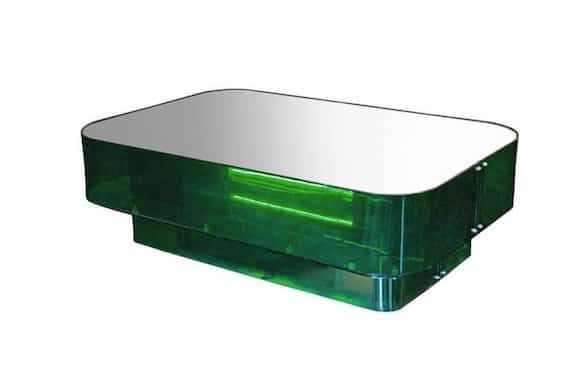

To experience this atmosphere of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll didn’t require a fortune. “It was really a lifestyle that didn’t matter if you’re rich or poor,” Bromley explains. The high-low appeal endures in trends like neon and lucite.

Perhaps the most significant ’70s contribution to residential interiors was the open floor plan. “The open plan is still the rage now. It has really flourished since the late ’70s,” Bromley notes. As social freedoms expanded, the functions of the household were no longer cordoned off as if behind a velvet rope. This soaring openness is an integral part of most contemporary interiors.

The open-plan home, popularized in the 1970s, persists today in this New York triplex by Amy Lau. Photo by Thomas Loof

Bromley splits his time between Manhattan and Fire Island, an LGBTQ enclave with its own architectural identity. Fire Island was a retreat for many in the Studio 54 scene, including Halston. The bacchanal atmosphere of both Studio 54 and Fire Island would wane with the onset of the AIDS crisis, which had a tragic impact on the design world.

Neoclassical sumptuousness met disco fabulousness in the hall of Studio 54. Photo courtesy of Bromley Caldari

Nowadays, Studio 54 is frozen in the popular imagination at its apex of fun, even though the quality of the parties declined after Rubell and Schrager’s 1980 sentencing for tax evasion. The club shut down six years later. Nobody had to watch Studio 54 slowly fade into obscurity.

The world grew up, but Studio 54 never did.