Every piece of wood tells a story, especially wood recovered from 400-year-old shipwrecks or from devastating earthquakes. Environmentally minded furniture designers and makers are telling the fascinating stories of reclaimed trees by giving them a second life in the form of functional furniture and lighting.

The combination of this unusually sourced wood with master craftsmanship results in one-of-a-kind pieces that can be cherished for generations. Here, we look at three extraordinary practitioners of this eco-friendly form of design.

Tréology

Tréology is a New Zealand–based company that continues a 150-year-old family tradition of furniture making. Its mission is to connect people with nature through contemporary organic furniture.

A reverence for New Zealand’s natural landscape is evident at all stages of the firm’s design process, from the inspiration behind its collections to its hands-on approach to sourcing the reclaimed wood it uses.

“The trees are rescued from rivers on the West Coast of New Zealand,” says Andrew Davies, Tréology’s cofounder and CEO. “It is a place I love to explore and take my family on adventure. I personally inspect and catalogue all our timber slabs before they are stored for drying. We love to connect our clients to the place where the tree was rescued, so we put the geographic coordinates of where the tree was found on our furniture.”

In addition to salvaging from rivers, Tréology uses wood that has been submerged in fjords and historical timber from earthquake sites in Christchurch. The ancient kauri timber employed in its lauded Umber collection comes from swamps in northern New Zealand, a sacred Maori site, where it had lain underwater for more than 45,000 years, preserved by the low oxygen conditions. Once retrieved, the logs must be given time to dry before they can be made into furniture.

“Waiting a few more years before we use them takes a bit of patience, but like a fine whiskey, good things take time,” Davies says.

Stickbulb

Stickbulb honors a different kind of landscape: the urban jungle of New York City. The award-winning lighting brand is committed to ensuring sustainability at every step in its process, and using reclaimed wood is an important part of that commitment. The firm’s first foray in this regard involved timber salvaged from the Coney Island boardwalk after it was destroyed by Hurricane Sandy, in 2012.

Now, it uses wood from local buildings that have been demolished, dismantled water towers and sustainably managed forests. Another way the firm minimizes its environmental impact is by having its sleek, sophisticated light installations manufactured within a five-mile radius of its New York City office.

Stickbulb’s creations appear simple on the surface, but the elegant wooden frames are ingeniously constructed so they can be plugged into and disconnected from various steel components without tools.

The modular systems are customizable, use as few parts as possible and are easy to maintain and recycle. They are beautiful to look at as well: The water-tower redwood employed, for instance, has a rich, warm tint from exposure to New York City weather on one side and from contact with water on the other.

Thomas Newman Studio

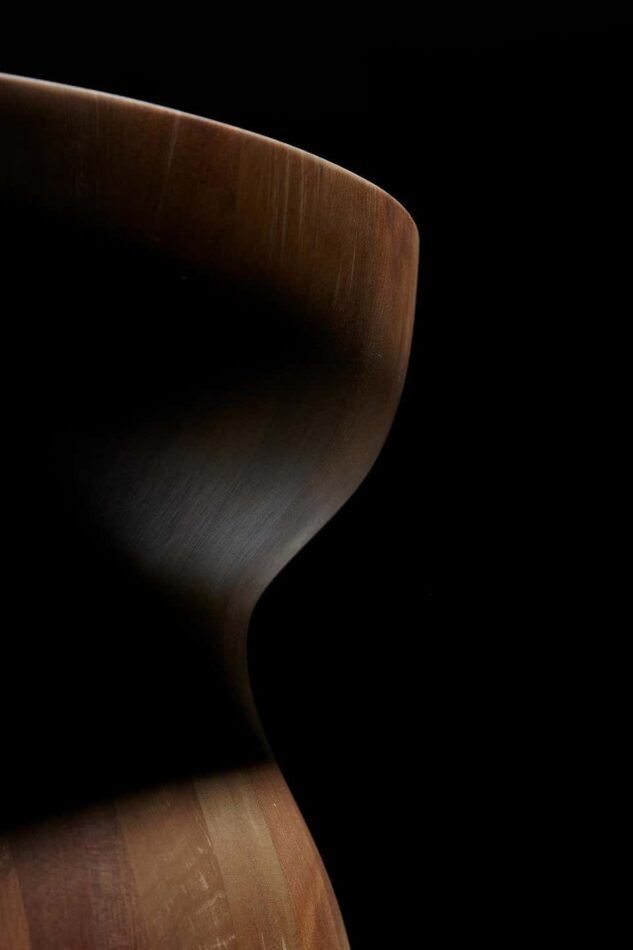

Thinking about the lifecycle of his creations comes naturally to Thomas Newman, the self-taught woodworker and master craftsman behind Thomas Newman Studio, in Hoboken, New Jersey.

“In my early career, I specialized in antiques restoration. In those days, furniture was made to last for generations. Veneers, when used, were sawn thick and could be easily patched, repaired and refinished,” Newman says. “When we use veneer, we saw it ourselves at least 1/16 of an inch thick. We stick it on wood cores. It is made to last.”

Until recently, Newman walked the woods with his loggers to personally select each piece of sapele mahogany — a sustainably grown hardwood — for the studio’s sensual, sculptural carved wood chairs and tables. The wood used in its exquisite bog oak furniture is ancient and often has a fascinating backstory. The 1,200-year-old timber for its Infinity screen, for instance, was part of the cargo of a Turkish ship sunk in the Dnieper River, in Ukraine, in a battle with Russians soldiers in the 1600s.

“Trees have a yearning to live again, perhaps to provide the beauty, strength, and utility to serve man, even to become an object of great artistic worth.” George Nakashima wrote in The Soul of a Tree, a book Thomas Newman considers crucial reading.

By making beautiful, long-lasting pieces that are gentle on the environment and telling incredible stories through their craft, these makers are honoring nature and the materials they work with.