September 13, 2020For 100 years, Architectural Digest has lived a double life. Born in Los Angeles in 1920, it initially presented the American West as a bastion of traditional European design, “replete with stately Mediterranean-style manses, sun-kissed Italianate gardens and picturesque reflecting pools,” as the magazine’s current editor, Amy Astley, writes in a newly released book celebrating its centenary. But then, cataclysms comparable to those the world faces today sent brilliant European architects, including Richard Neutra and Rudolf Schindler, to California. Soon, the magazine was also focusing on futuristic homes of glass and steel. And so, the double life was born.

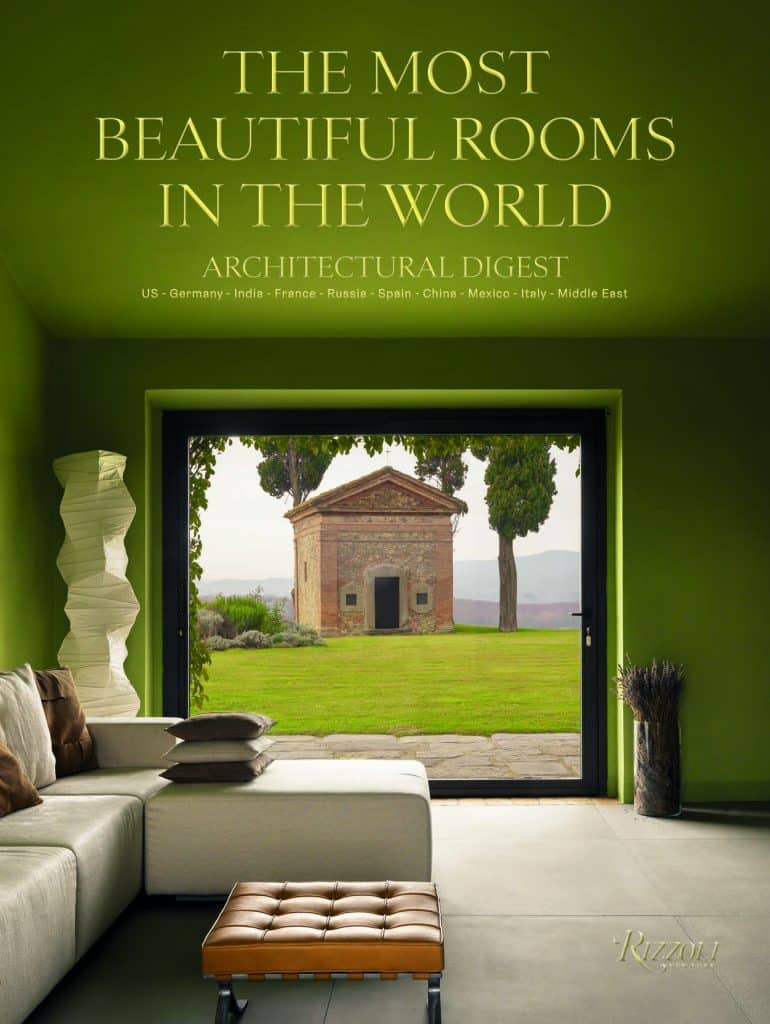

Architectural Digest, of course, expanded far beyond California. These days, the flagship magazine, published in New York by Condé Nast, has nine international siblings, with recent startups in Russia, China, India and the Middle East joining more established ADs in Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Mexico. The editors of the 10 editions selected their favorite projects, which Marie Kalt, the editor of AD France, then culled and assembled into a volume titled (with ample justification) The Most Beautiful Rooms in the World. The book, published by Rizzoli and limited to projects from the past 10 years or so, was conceived before the pandemic, and it captures an era of open borders and globalization. As Condé Nast’s artistic director, Anna Wintour, writes in her introduction, “National identity is largely what you make of it. Where we feel we come from, who we are, what country we call home — these are ideas that are changing all the time.”

There’s no question that global trends exist in interior design, Kalt tells Introspective. Now, for example, every rich collector, regardless of nationality, seems to have a yen for chunky wooden furniture, particularly the work of Guillerme et Chambron and Pierre Chapo, but also, as in the Barcelona home of interior designer Gabriel Escámez, pieces by anonymous craftsmen.

Even as it illustrates those commonalities, the book attempts to illuminate national differences. Each of the 10 editors, Kalt says, “has really tried to get the spirit of the times in their own country and not make it a blur.”

Craft traditions are emphasized in Mexico and India, where even the sophisticated homes designed by Studio Mumbai’s Bijoy Jain (touted as “a future candidate for the Pritzker Prize”) use only local materials and products, resulting in a look that AD India editor Greg Foster calls “Desi wabi sabi.” (India exports but hardly imports furniture; as Foster notes, Pierre Jeanneret’s Chandigarh pieces are “a little bit of India found in almost every AD home the world over.”)

What about the houses of one-percenters living in wealthy countries? Are they interchangeable, regardless of location? Not completely.

For instance, Kalt writes about France’s interior designers, “The use of color is not always their forte. [They] seem to prefer subtle monochromes of whites and beige tones.” But in Spain, just a few pages away, designers use color “freely and happily,” she notes. Spain is also a place where rooms are subject to rearrangement. We are “open to all suggestions,” writes AD Spain editor Enric Pastor, “but we draw the line at immobility.”

Or consider Germany versus the United States. In the birthplace of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe whose mantra was “Less is more,” rooms are often minimalist to the point of asceticism. But in America, more is more; it took the combined efforts of Thad Hayes, John Gachot and the late Paul Fortune to fill the television room of Marc Jacobs’s Manhattan townhouse almost to bursting.

In the Middle East, design tends to be earnest — whether it’s the home an Arab prince who studied architecture created for himself in Riyadh or the mansion of a Palestinian billionaire using grandeur as a political statement. By contrast, in Italy, the country that produced Ettore Sottsass and Giò Ponti, most designs have an “inherent irony,” says AD Italy editor Ettore Mochetti.

And then there are the distinctive environments born out of personal relationships. Developer Craig Robins was friends with Zaha Hadid for years before she added an all-white and entirely Zaha-esque bathroom to his Miami house.

Designers Ariel Ashe and Reinaldo Leandro may have saved their best work for Ashe’s sister and brother-in-law, Alexi Ashe and Seth Meyers, of late-night TV fame. Ashe + Leandro are part of a cohort of youngish American designers whose utterly original work jumps out from the pages of the book; others are Apparatus founders Gabriel Hendifar and Jeremy Anderson and Manhattan architect Giancarlo Valle.

Not that the older generation has gone missing. “You couldn’t do a book like this without Peter Marino,” says Kalt, who included the architect’s own Rocky Mountain ski house, a lesson in icy perfection.

But the aesthetic that best defines the interiors included in the book is eclecticism — the mixing and matching that has become the design world’s lingua franca. Of course, even eclecticism has variants, from the lush interiors of Studio KO (represented by a brass-trimmed flat in Paris) to the spare environments of London-based John Pawson (a trim-free Manhattan living room for Scandinavian antiques dealer Jill Dienst, of Dienst + Dotter).

One way or another, nearly all the interiors in the book combine shiny and dull, thick and thin, restrained and ornate and, especially, old and new. It’s hard to imagine a more powerful modern statement than that made by an Ekstrom armchair, designed in the 1980s by Terje Ekstrom, of Norway, and seemingly composed of thick bent pipes: A pair of these in school-bus yellow appears alongside 17th-century furniture in a Madrid living room by interior designers Las 2 Mercedes, while another set, in fire-engine red, mingles with priceless antiques in a Bologna home designed for antiquarian Maurizio Nobile by architect Enricho Bianchini. Both arrangements prove that the shock of the new and the comfort of the old together can make great rooms.

In a similar way, The Most Beautiful Rooms in the World proves that the two lives of Architectural Digest — the traditional and the modern — have merged over the magazine’s 100 years.