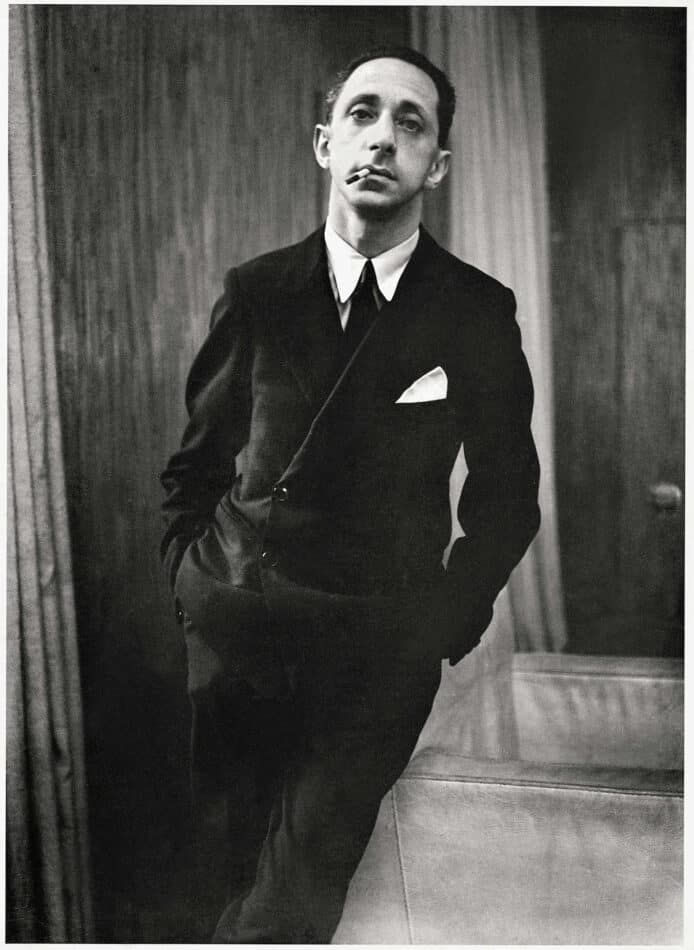

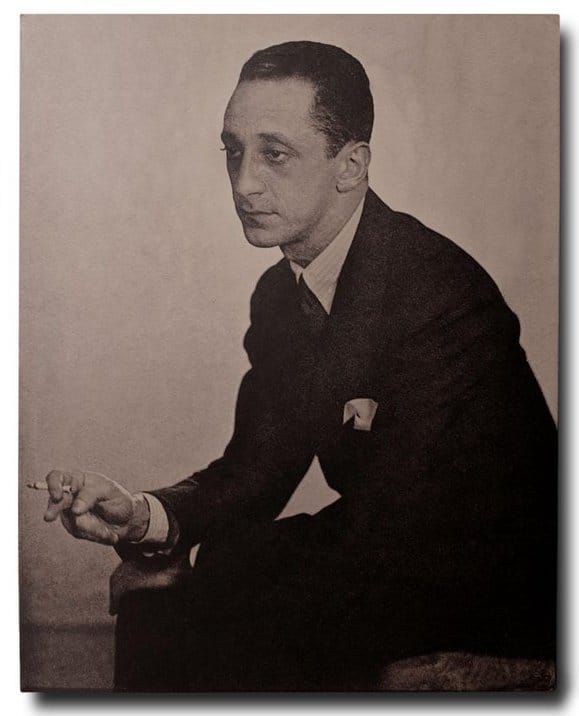

The life of Jean-Michel Frank (1895–1941), the renowned designer of furniture and interiors, was one of great privilege, prodigious talent and tremendous tragedy. His origins were exceptional and curious. His father, León Frank, was a financier and scion of a German banking family, one of 11 siblings who settled around Europe and the United States.

León married his niece Nanette Loewi, the daughter of a sister who had married a rabbi in Philadelphia. (One of his nephews was Otto Frank, Anne Frank’s father.) León and Nanette had three sons, the youngest of whom was known as Jean. (He didn’t call himself Jean-Michel until his business took off, around 1930.)

The young Frank was an unusual boy, described by one classmate as “a sort of child-woman, ageless and sexless.” In fact, he was so effeminate that he was exempted from conscription at the start of World War I. His two older brothers, however, were drafted and killed at the front within two weeks of each other in the summer of 1915.

Despite this sacrifice for his adopted country, León, because he was German-born, had his bank accounts seized and business transactions terminated by the French state, which put him under house arrest. This swift succession of calamities was too much for him, and he committed suicide by leaping from a window.

Ironically, because Jean was born in France, he was able to inherit his father’s confiscated fortune. Meanwhile, his mother sank into such an extreme depression that she had to be institutionalized in Switzerland and never recovered. She died in 1928.

With so much family catastrophe, Frank abandoned his study of law, probably taken up to please his parents, and instead lived off his inheritance, chain smoking and haunting nightclubs, bingeing on cocaine and opium and traveling to fashionable destinations in southern France, Spain and Italy. His life was louche but highly cultured, as he quickly became part of the rarefied circle of cosmopolitan creatives who would define the era.

Always something of an aesthete, he began dabbling in interior and furniture design in 1920, even though he had no aptitude for drawing or craft. In his first project, for a friend, he designed a table wrapped in stingray skin, and its combination of a basic form with an exotic material created a sensation.

It was in pursuit of this reductive elegance that in 1936 he came to design the Parsons table. The piece is now ubiquitous because of its simplicity, but he conceived its archetype as a basic armature that might be wrapped in some rarefied material like ivory, mica or shagreen. This and other projects are detailed in the sumptuous and humungous new monograph Jean-Michel Frank (Assouline).

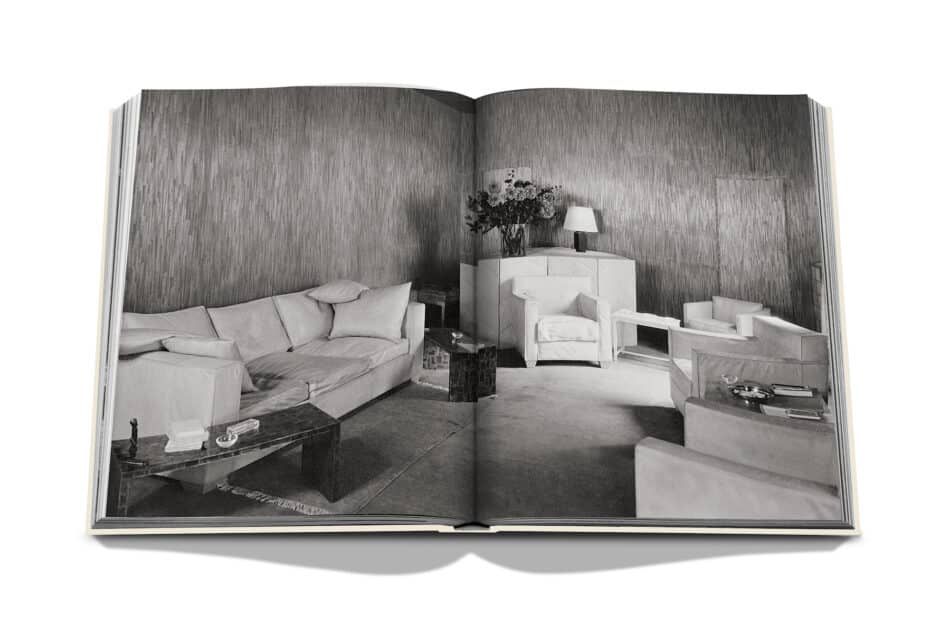

His signature look, which came to be known as luxe pauvre, was soon all the rage among Parisian trendsetters. Among these was Nancy Cunard, whose Île Saint-Louis apartment Frank turned into what looked like a chic cloister. For his own Left Bank apartment, he collaborated with the designer and cabinetmaker Adolphe Chanaux, replacing the 17th-century paneling with straw marquetry, covering the sofas in white leather and turning the capacious bathroom into a tomb-like realm with walls and floor lined in a dramatic black-veined white marble.

He furnished his study with only a simple chair and a desk wrapped in leather, from Hermès, of course. After dining at the apartment, Jean Cocteau wrote to a friend, “Very charming young man, pity the burglars took everything he had!”

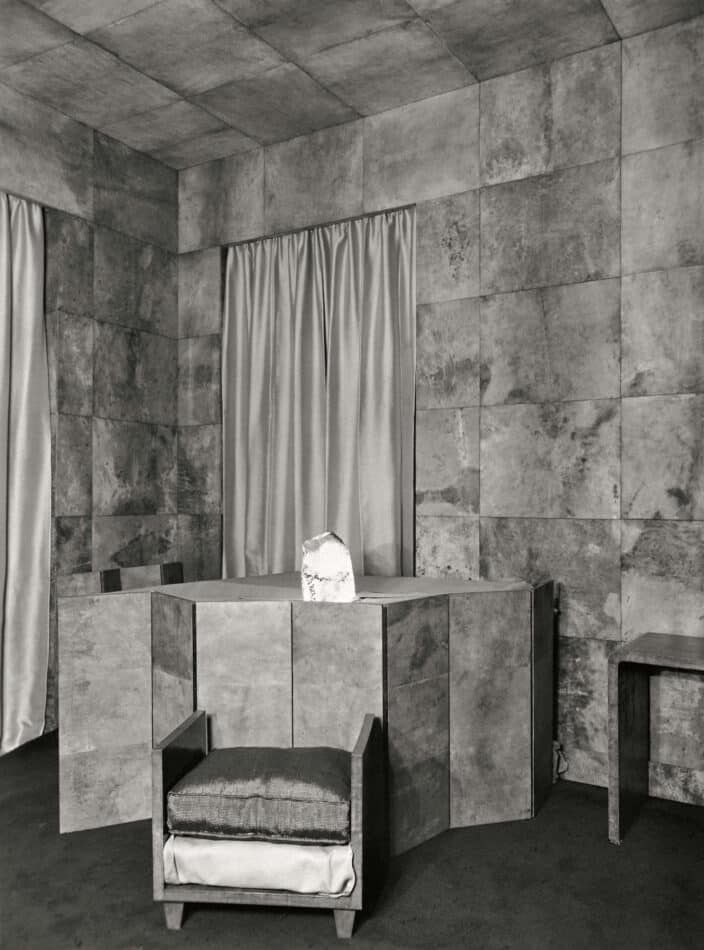

Luxe pauvre may not have appealed to Cocteau, but it did to another great Parisian tastemaker, the Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles. A great patron of the Surrealists, she commissioned Frank to redo her grand Beaux-Arts hôtel particulier. He paneled the walls in squares of vellum and furnished the rooms with block-like sofas and armchairs upholstered in pale glove leather, tables of straw marquetry, lamps made of chunks of quartz and doors wrapped in bronze. He had Man Ray photograph the rooms before the vicomtesse added her portraits by Balthus and Salvador Dalí and other personal accessories, preferring it spartan.

In 1927, Frank met his aesthetic soul sister, arguably the originator of luxe pauvre: Eugenia Huici Arguedas de Errázuriz, a Chilean silver-mining heiress, famous beauty and patroness of the avant-garde, whom Pablo Picasso affectionately called “my other mother.”

Later, Frank famously quoted her as saying, “Elegance is elimination.” Errázuriz had begun pioneering an austere interiors style around the start of World War I, whitewashing the walls of her country house as peasants did, covering its windows in unlined linen and leaving the house’s red-tiled floors bare. Young tastemakers were enchanted, even Cecil Beaton, who adored frippery: “Her toast was a work of art!” Frank became her acolyte, and she encouraged him to expand his vision, showing him how to interpret period furniture in a fresh contemporary way.

So, while he dreamed of creating rooms in multiple tones of beige, Frank also began exploring the decorative potential of brilliant color. Much impressed by the stunning Ballets Russes sets that Georges Braque, Henri Matisse and Picasso had created for his friend Sergei Diaghilev, Frank remarked, “I wish one could see more artists collaborating in arranging houses, the result would be, at the very least, something of our time, and alive.”

Once he had sufficiently established himself in the design world, such artistic collaborations are exactly what he pursued.

By 1930, he and Chanaux had joined forces, with Frank serving as artistic director of Chanaux & Co. The firm established a Left Bank workshop staffed with artisans who specialized in woodworking and varnishing and were expert in accomplishing all the decorative feats Frank required in vellum, mica and straw. It opened a showroom on the posh rue du Fabourg Saint-Honoré.

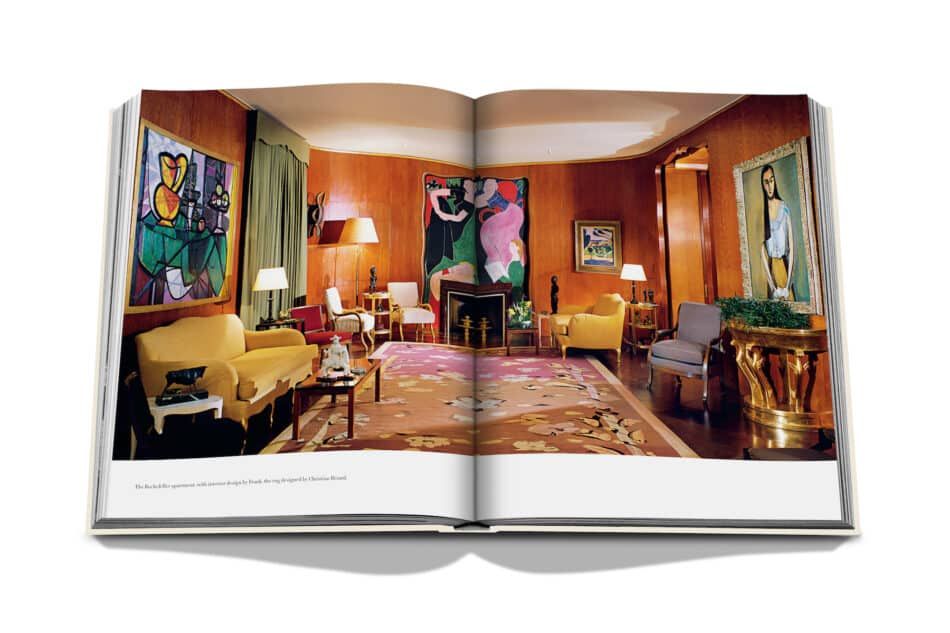

Frank recruited artists to design furniture for him. Salvador Dalí produced screens with Surrealist scenes; Christian Bérard designed flamboyant floral carpets; Emilio Terry conceived fanciful consoles and mirror frames; and Alberto and Diego Giacometti crafted bronze and plaster urn lamps and ceiling fixtures.

Emboldened by his collaborations with Bérard, Frank started creating increasingly colorful and experimental interiors. He outfitted the apartment of Elsa Schiaparelli, another beloved friend and mentor, with an orange leather sofa and black rubber draperies, upholstering the dining banquettes in quilted blue chintz. For her salon on rue de Berri, he produced a purple sofa, scarlet chairs and white and gilt bookcases. Schiaparelli was so pleased she even had Frank design the bottle for her first perfume, Salut!

By now, Frank was designing interiors all over the world. One of his most dramatic was the San Francisco penthouse he created for the eccentric railroad heir Templeton Crocker, which featured a sun room furnished with a brave mix of animal skins, Navajo rugs and elegant tables modeled on ones recently discovered in King Tut’s tomb.

Another sumptuous, and colorful, project was the Fifth Avenue apartment of Nelson and Mary Rockefeller, which boasted oak paneling, the Giacometti brothers’ gilded tables and Bérard’s floral carpets.

The start of World War II, just as Frank was finishing the Rockefeller apartment, brought Chanaux’s operations to a halt, as most of the staff was drafted. By June 1940, Frank had fled to Buenos Aires, where he had been working on the Born residence just outside the city, one of his most ambitious projects.

Since he already knew a number of wealthy Argentines from Paris, thanks largely to Errázuriz, Frank was not without friends or new clients. He soon produced another superlative project, the Llao Llao Hotel, in Patagonia, for which he designed a striking and now iconic lounge chair upholstered in doe hide.

Despite the horror of the war and its threat to his extended family in Europe, it seemed that Frank might flourish in Buenos Aires. A stay in New York that January ended this possibility. The reason for the trip remains a mystery — perhaps to see an old lover or finish some details on a few projects there and buy some materials — but three months later, as he prepared for his return, he leaped from a building on the Upper East Side. Frank received a mere 100-word obituary in the New York Times and soon slipped into obscurity.

Today, of course, his influence is everywhere. And his original designs are prized — ironically, considering Frank’s tumultuous life — for their serene and simple beauty.