“Koloman Moser wanted to fill every small niche of everyday life with art,” says Florian Kolhammer, of the Viennese gallery Kunsthandel Kolhammer, which specializes in Vienna Secession–era creations. “This particular idea still inspires designers today.”

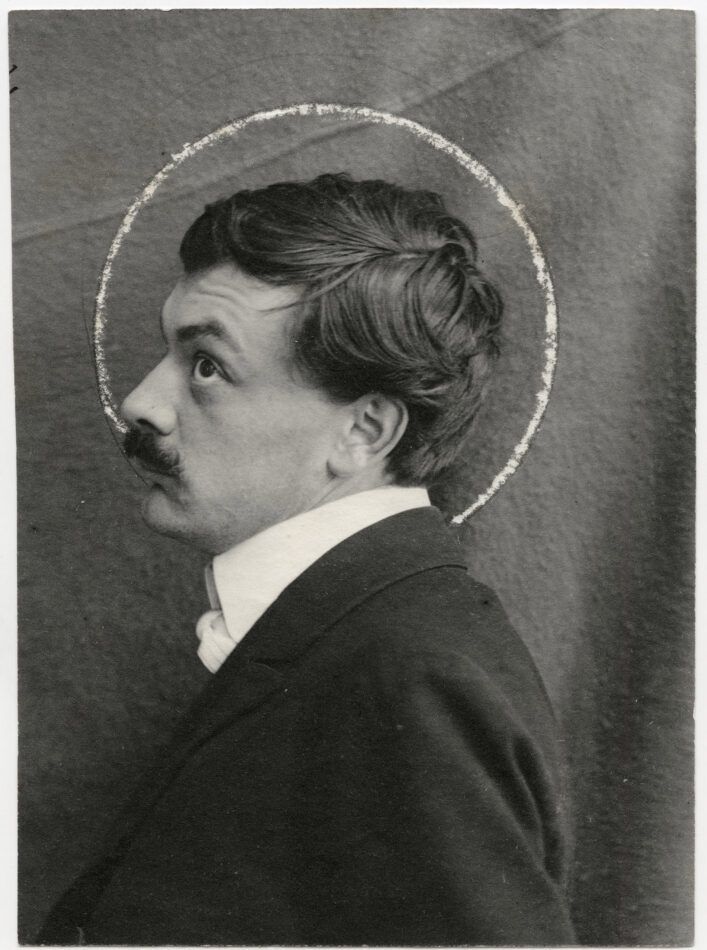

Founded in 1897, the Vienna Secession, a union of artists and designers determined to upend Austria’s artistic conservatism, was committed to making total works of art: Gesamtkunstwerken. The group’s members included marquee names like Josef Hoffmann and Gustav Klimt, but it was Moser, termed the “all-round artist,” who truly embodied its principles, working in the fields of painting, graphic design, typography, furniture, jewelry, fashion, interior design and scenography.

“Moser, together with Hoffmann, created a decisive stepping-stone in enabling the modern design of the 20th century,” says Christian Witt-Dörring, guest curator of the exhibition “Koloman Moser: Universal Artist between Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffmann,” currently on view at the MAK in Vienna. “They were among the first to leave the reuse of historic styles behind in creating a purely modern design language.”

Aptly described as the most comprehensive solo exhibition of Moser’s oeuvre to date, the MAK show contains hundreds of the artist’s pieces, brought together in commemoration of the 100-year anniversary of his death. It will move on to Villa Stuck, in Munich, in May.

Born in Vienna in 1868, Moser briefly attended trade school, honoring his father’s wish to see him in commerce. But he soon surrendered to his artistic inclinations, enrolling in 1885 in Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied painting.

When his father died unexpectedly in 1888, leaving the family in financial straits, Moser helped out by doing illustrations for books and magazines. Meanwhile, he continued his painting studies, at the academy and then at the School of Arts and Crafts, starting in 1892. That was also the year that Moser, along with other young artists revolting against the Viennese art world’s devotion to naturalism, formed the Siebner Club, the precursor to the Secession.

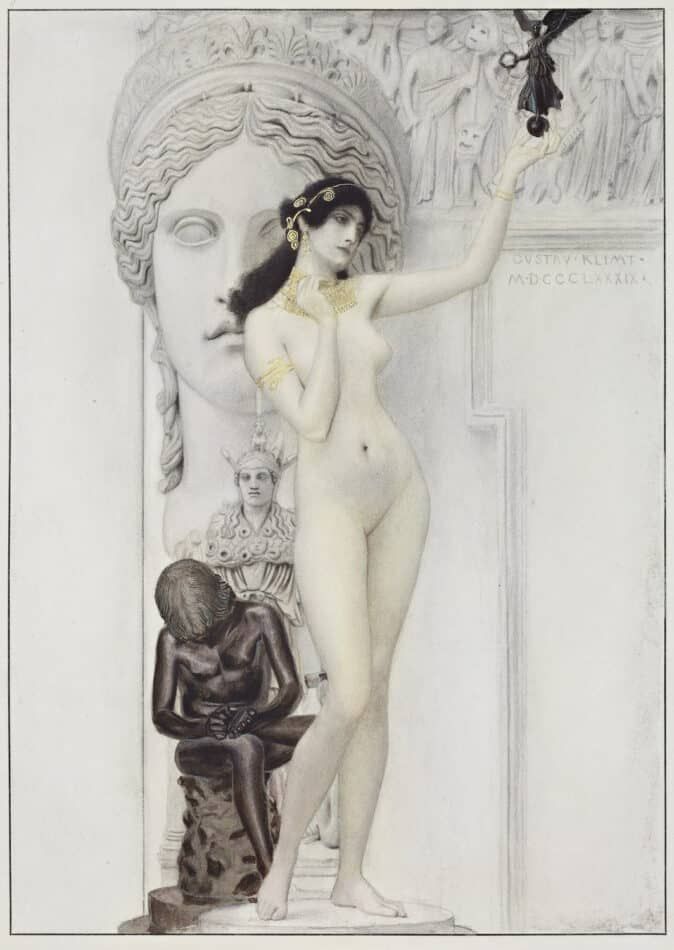

Moser’s introduction during his last term at school to Klimt’s Allegory of Sculpture proved a turning point for the young artist. “From this moment on, Moser’s drawing style changes,” Witt-Dörring notes in the exhibition’s catalogue. “Primarily inspired by the art of Japan, [Klimt] introduces new paper sizes, fragmented image details, and an emphasis on the line as opposed to the surface.” A year later, Moser together with Klimt, Carl Moll, Joseph Olbrich and Hoffmann founded the Vienna Secession.

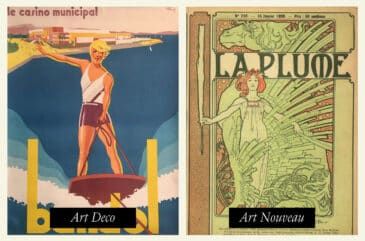

Looking to the English Arts and Crafts Movement, with its guiding principle of unity of the arts, the group attempted to bring art back into everyday life and introduce a local modernism to fin-de-siècle Vienna. Moser, whose membership in the club also afforded him entry into upper-class Viennese society, turned his back on oil painting and forged ahead with Gesamtkunstwerk.

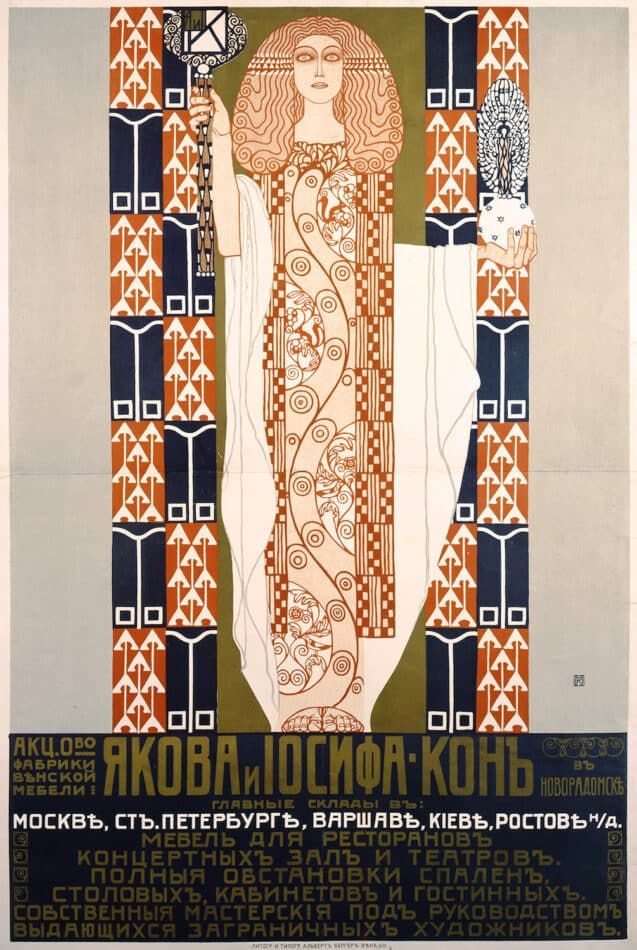

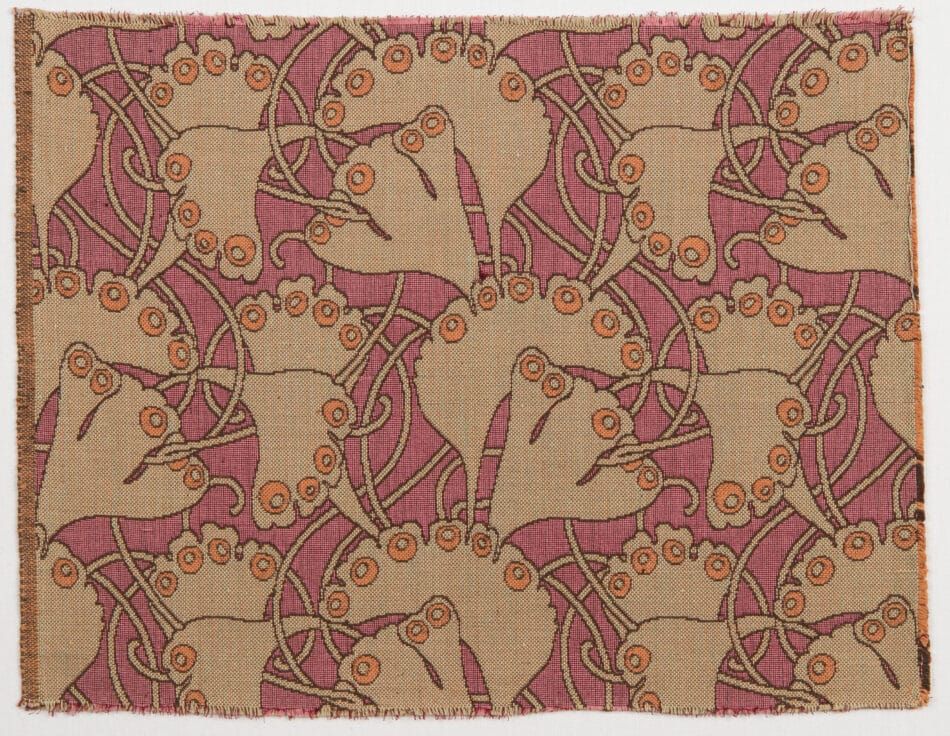

He created everything from exhibition design to facade ornamentation for the Secession Building (designed by Olbrich) to graphic materials for the group, like its letterhead, exhibition posters and the layout and fonts of its monthly magazine, Ver Sacrum. Moser also produced posters and advertisements in his “modern style” for various companies. In 1898, he presented his first decor pieces, including hand-knotted rugs and cushion covers.

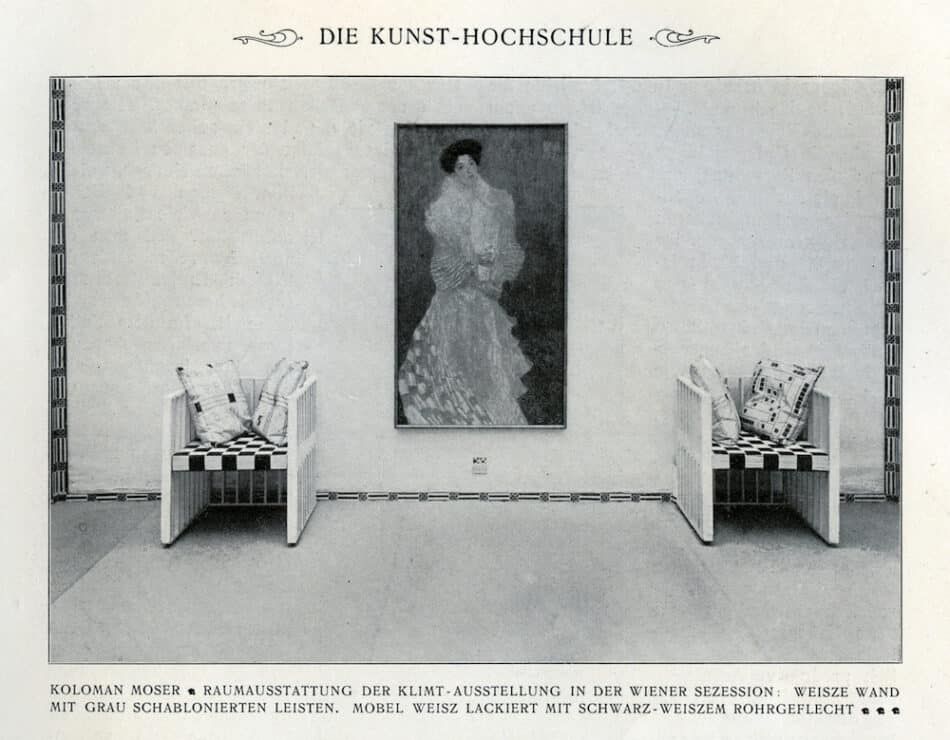

In 1899, Moser began what would become a lifelong professorship at the School of Arts and Crafts, which he saw as an opportunity to pass on the Succession’s new design vocabulary to a younger generation. Moser’s appointment, along with that of Hoffmann, was facilitated by the influential architect Otto Wagner, who joined the Secession that same year. Moser’s repertoire now expanded to include furniture, ceramics and patterns like his trademark checkerboard design. He also moved into scenography and fashion and established himself as an interior designer.

“Moser’s move to a reduced geometric design vocabulary, the so-called Viennese style, from the year 1900,” Witt-Dörring writes in the catalogue, “is now fully developed in these interior designs.” The artist decorated his own home in 1902, after which he received a series of important commissions, notably the villa of textile industrialist Fritz Waerndorfer. It was Waerndorfer who provided the financial support that enabled Moser and Hoffmann in 1903 to found the Wiener Werkstätte, a platform for fully realizing their ideal of Gesamtkunstwerk.

“Moser’s work influenced artists all around the world. The Wiener Werkstätte had branches in all the major cities at that time, including St. Petersburg, London and New York City,” Kolhammer says. “He was one of the first designers to consequently reduce shapes of furniture and art objects without forgetting the high-quality ornaments that were so defining for the Wiener Jugendstil. He was also the first Austrian designer who invented a complete corporate identity — in this case, that of the Wiener Werkstätte.”

Two years later, Moser and other like-minded Secession members left the group. He married Edith Mautner von Markhof, the daughter to one of Austria’s great industrial barons, and his work thrived.

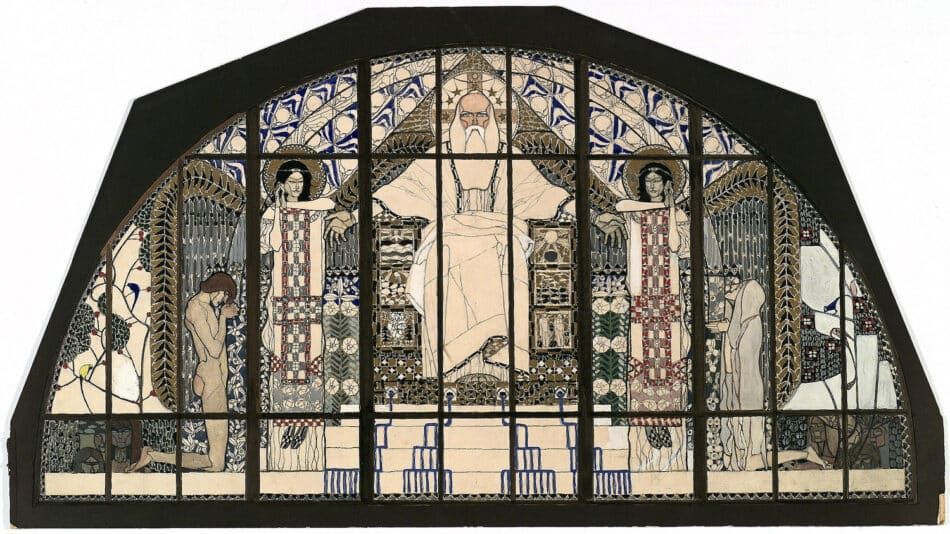

“Koloman Moser had a great influence on the works of the Wiener Werkstätte in the early stages,” says Wolfgang Karolinksky, of Vienna’s WOKA gallery, which offers originals and reeditions of Moser’s. “We see great interest in designs for the Steinhof Church, the cubistic Reininghaus table lamp, the classic seven-ball chandelier from the Wiener Werkstätte and the wall lamp for the Flöge fashion house.”

But in 1907, the Wiener Werkstätte ran into financial trouble. Losing faith in the unity of the arts and disillusioned with the group’s dependency on wealthy patrons like Waerndorfer, Moser left the Werkstätte. He returned to his original discipline, painting, which he continued to practice until his untimely death from cancer, in 1918.

Today, Moser’s work, from his metal vases to his jewelry to his interiors, remains sought-after and revered. “By creating a rare harmony between sensuality and functionality, he involves the art lover in a conversation with his designs,” says Witt-Dörring. “The first impression received on looking at his creations is never the last one. His pieces do not give everything away at first sight. They evolve with you, and vice versa.”