Think of the Anglepoise lamp and what comes to mind? Ben Whishaw’s Q explaining the latest gadget wizardry to Daniel Craig’s James Bond in No Time to Die, aided by an Anglepoise Type 75? Roald Dahl in his hut writing The BFG by the light of his Original 1227 (the same model that has sat proudly on the desk of Her Majesty the Queen)? Or maybe it’s the 1978 single from the Soft Boys “(I Want to Be an) Anglepoise Lamp”?

It would be impossible to list every writer, designer, photographer and filmmaker who has worked deep into the night helped by the illuminating beam of an Anglepoise. Its anthropomorphic design has given it a quality that goes beyond its technical genius, imbuing it with warmth, character and a soothing presence.

No wonder it was chosen in 2009 — alongside the Mini automobile, red telephone kiosks, Penguin books and the London Underground map — for a series of stamps dedicated to British design classics. A lamp so beloved surely deserves to have its story told. How fortunate then that Jonathan Glancey explores the origins and influence of the Anglepoise in his excellent book, Spring Light (Rizzoli).

How the Anglepoise came to be is the stuff of design legend: In 1932, a vehicle-suspension engineer by the name of George Carwardine joined forces with a West Midlands springs manufacturer, Herbert Terry & Sons, to create a mechanism by which opposed springs would, as Carwardine explained, exert a “unidirectional constant force” on a pivoted lever that could counteract the force of gravity.

This invention was not destined for an auto but for a lamp Carwardine was developing. The innovation would allow the piece’s articulated arm to be moved with ease to almost any position and remain there.

Initially called the Equipoise, the desk lamp was renamed Anglepoise for patent-registration purposes. It found immediate success on its launch, in 1934, with demand quickly outstripping supply.

However, the four-spring design was considered too industrial for domestic settings, so the Carwardine-Terry team set to work creating a streamlined version, still found in offices and on bedside tables today: the three-spring Original 1227.

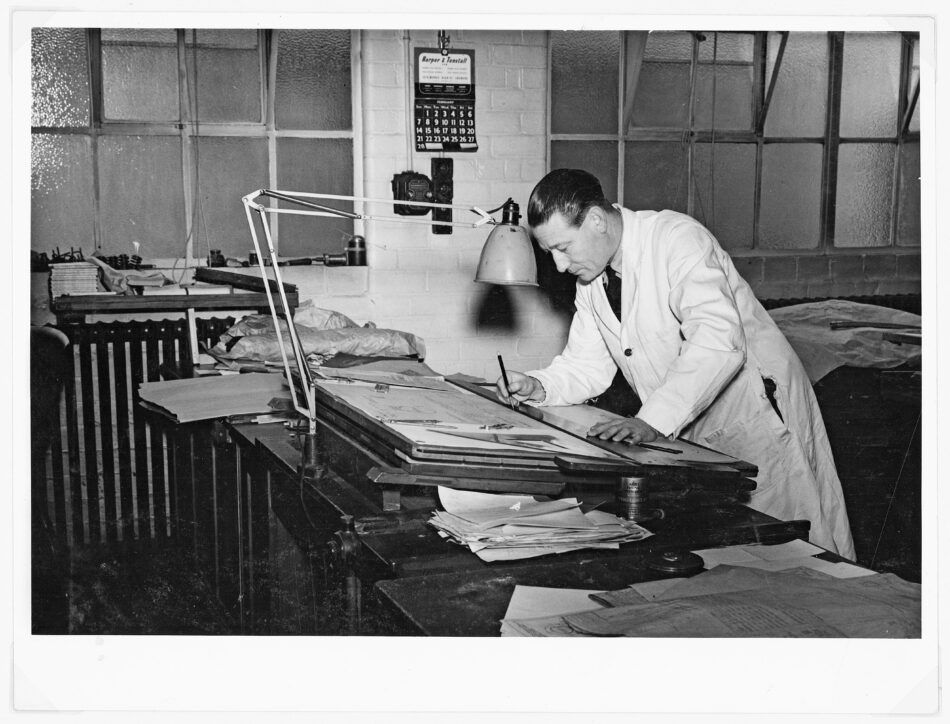

As the product of engineering acumen rather than fashion, the Anglepoise soon became a favorite among modernist architects and designers, who interpreted it as “a machine for lighting,” just as Le Corbusier had reimagined the house as “a machine for living in.”

Of course, it had rivals from the first. The 1930 Bestlite — another British success story — was one of the earliest Bauhaus-influenced designs, created by Robert Dudley Best, who had studied under Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus in Dessau. German modernist Karl Trabert’s 1930s desk lamp for Schanzenbach & Co. was notable for its domed shade above a hinged arm.

The Anglepoise’s success, however, was grounded not just in the ingenuity of its design but also in its marketing and affordable pricing. Terry was quick to adapt new colors and finishes for middle-class homes, shops and restaurants.

When Harrods opened its beauty salon in 1936, customized Anglepoises featured in its brochure. By the 1960s, Anglepoise had adopted the slogan “The lamp with the personal touch.”

By the 1980s, the most intense competition to the Anglepoise was coming from Italy, with firms such as Artemide offering the Tolomeo desk lamp, by Michele de Lucchi and Giancarlo Fassina, and the Tizio lamp, by Richard Sapper (the Tolomeo, incidentally, featured the patented Carwardine mechanism used in the original Anglepoise, proving that even half a century later, it was an engineering feat hard to beat).

Anglepoise fought back with notable partnerships with prominent designers, including collaborations with Paul Smith and Margaret Howell on several versions of the Type 75 desk lamp, conceived by Sir Kenneth Grange.

The image many Americans associate with the Anglepoise is from Pixar’s Luxo Jr., an Oscar-nominated 1986 animated short whose title character was later integrated into the company’s logo. In point of fact, the Luxo is not strictly an Anglepoise but a version of Carwardine’s 1208 lamp modified and sold by a Norwegian importer named Jac Jacobsen.

In 1936, Jacobsen saw the potential of the design and sought to acquire the licensing rights for Norway. He subsequently designed his own four-spring version, the L-1 — aka the Luxo — securing the rights to sell it outside Great Britain and the Commonwealth.

It was quickly embraced in the United States after its launch there in 1952, and although the original British design morphed somewhat on its way to becoming cultural shorthand for one of Hollywood’s most successful studios, the bones of Carwardine’s creation are still recognizable.

Anglepoise has suffered the trials and tribulations one might expect for any company in business nearly ninety years. But it has assured itself a place as a heritage British brand alongside such names as Burberry, Wedgwood and Bentley.

“The Anglepoise design is not only functional but artfully crafted to appear completely artless,” notes New York–based furniture dealer Otto Binx, who specializes in modern and postmodern design. “It was industrial chic before that was even a thing, from its bonnet-like shade to the series of joints that mirror our own neck, hips, knees and ankles. For me, it is a symbol of British excellence and humble perseverance.”