It’s not like the photographer Berenice Abbott, who died in 1991 at the age of 93, has been overlooked. She is widely known, indeed celebrated, for her iconic portraits of some of the most glamorous denizens of 1920s bohemian Paris. And although less familiar, her photos of the deserted streets, aging tenements and rising office towers of Depression-era New York have been critically recognized as nothing short of groundbreaking.

Even her relatively obscure work as a science photographer has received an admiring reappraisal in recent years. Recognized for having dramatically advanced the medium’s aesthetics and techniques (earning four patents along the way), not to mention the ambition of her subject matter — the principle laws of physics — she has been favorably compared to two early masters of modernist experimentation: her mentor Man Ray and László Moholy Nagy. Yet, despite all this, Abbott has never been heralded as one of the defining giants of 20th-century photography.

The new monograph Berenice Abbott: Portraits of Modernity may well change that. Published by the Fundación MAPFRE to accompany an exhibition touring through its Barcelona and Madrid galleries, the book contains critical essays and 190 duotone images revealing the breathtaking scope, perceptive daring and bracing realism of her work.

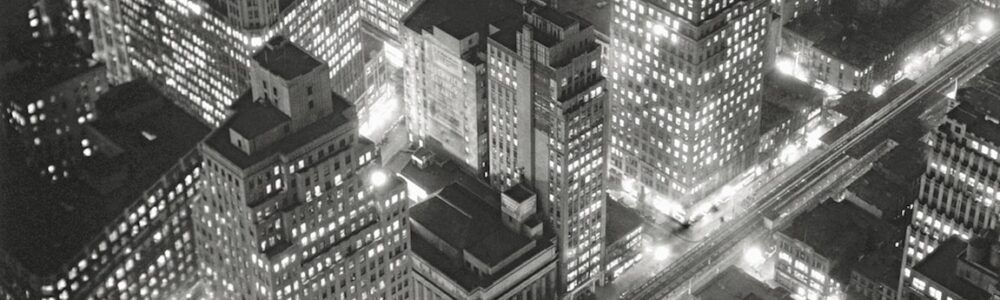

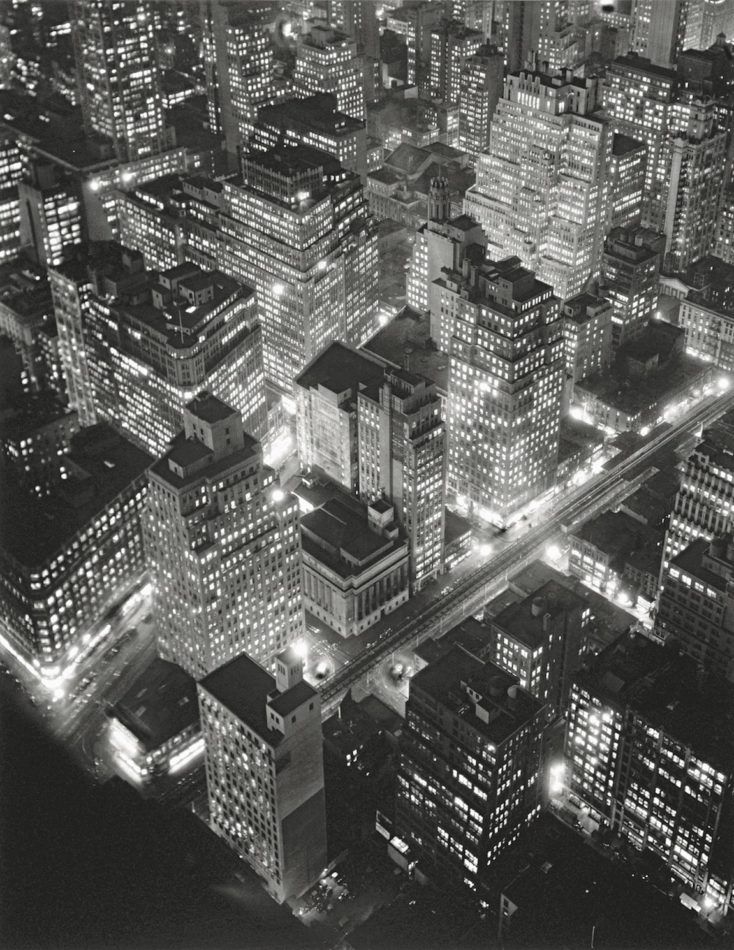

A number of Abbott’s images of New York appear to have been shot by drone or, in the technological equivalent for the day, a dirigible. They actually entailed her stationing herself precariously on the rooftops and ledges of the skyscrapers along Wall Street and Midtown.

That feat recalls the famous photograph of Abbott’s contemporary and fellow Ohioan Margaret Bourke-White taking a shot of the New York skyline astride one of the metallic eagle heads atop the Chrysler building. One can only wonder if a photograph of Abbott in a similarly heroic pose would have helped her recognition as the trailblazing documentarian she was.

But without her camera, Abbott was a guarded, often difficult and solitary soul. And that diffidence may have kept her from achieving the eminence she’s only now being accorded.

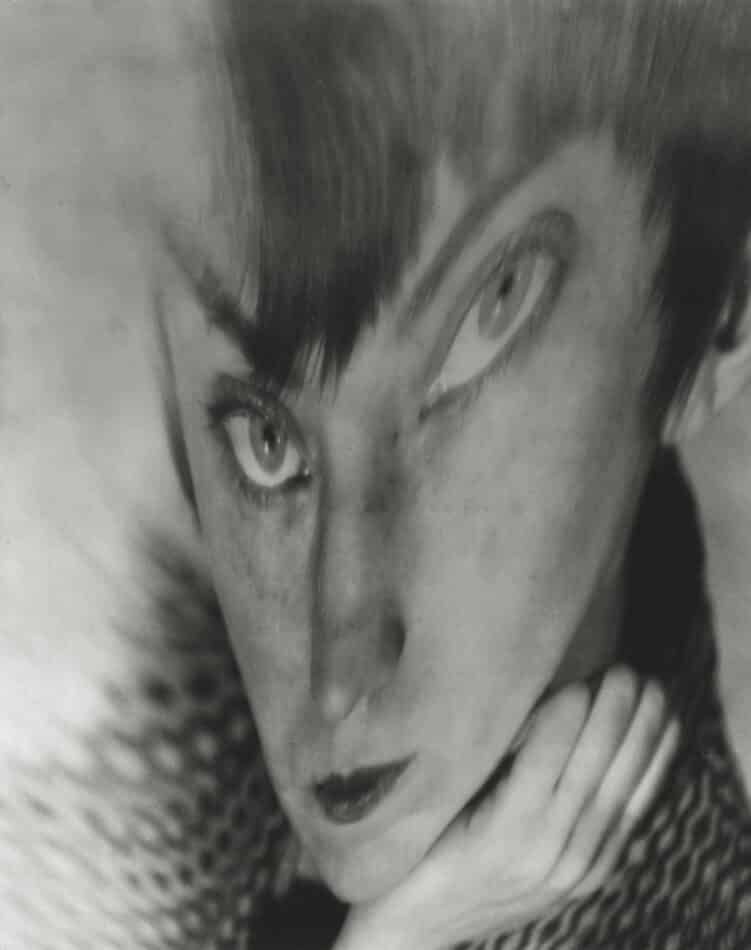

In 1918, at just 19, freckled, androgynous and with cropped hair, Abbott fell in with a crowd that included the lesbian writer and illustrator Djuna Barnes and the Dadaists Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. They encouraged her to follow them to Paris and study with the renowned sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. Unable to pay for her training, and barely surviving, Abbott took a job as Man Ray’s assistant. The miracles of the darkroom quickly converted her to photography, as did her paycheck, and Man Ray tutored her in its fundamentals.

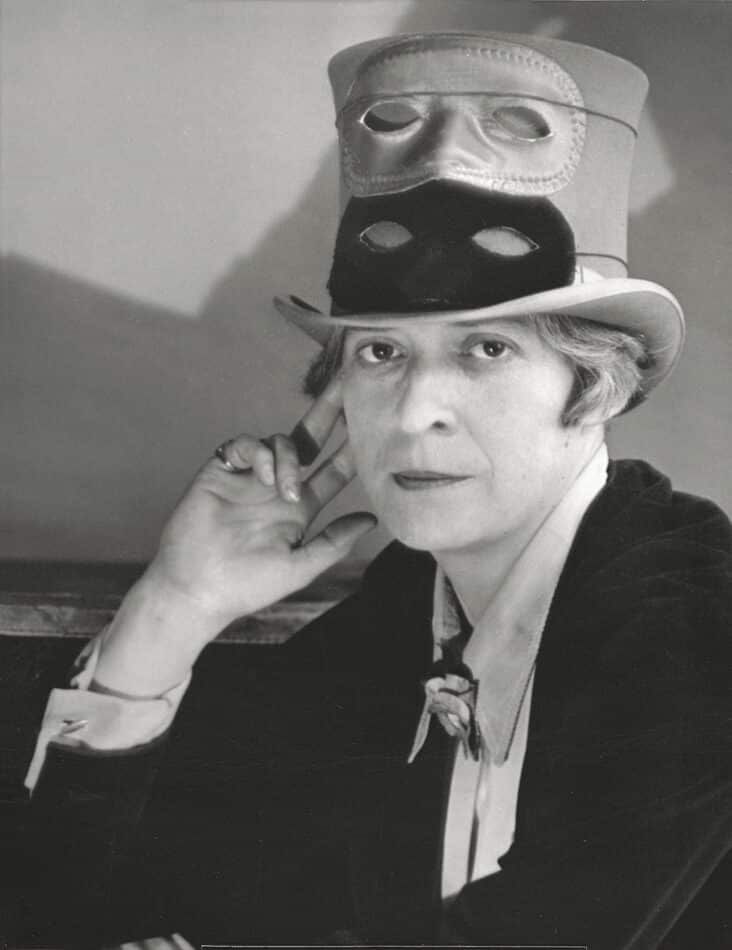

By 1926, she’d set up her own studio with backing from Peggy Guggenheim, the American heiress and art patron. André Gide, Jean Cocteau, Janet Flanner and James Joyce were among the luminaries and socialites who came for sittings. Her subversive lens made for riveting portraits. In image after image, women pose confidently before the camera, seemingly empowered by this new modern age. The men, in contrast, appear pensive, enervated and feminized by it. Such depictions didn’t deter clients, however.

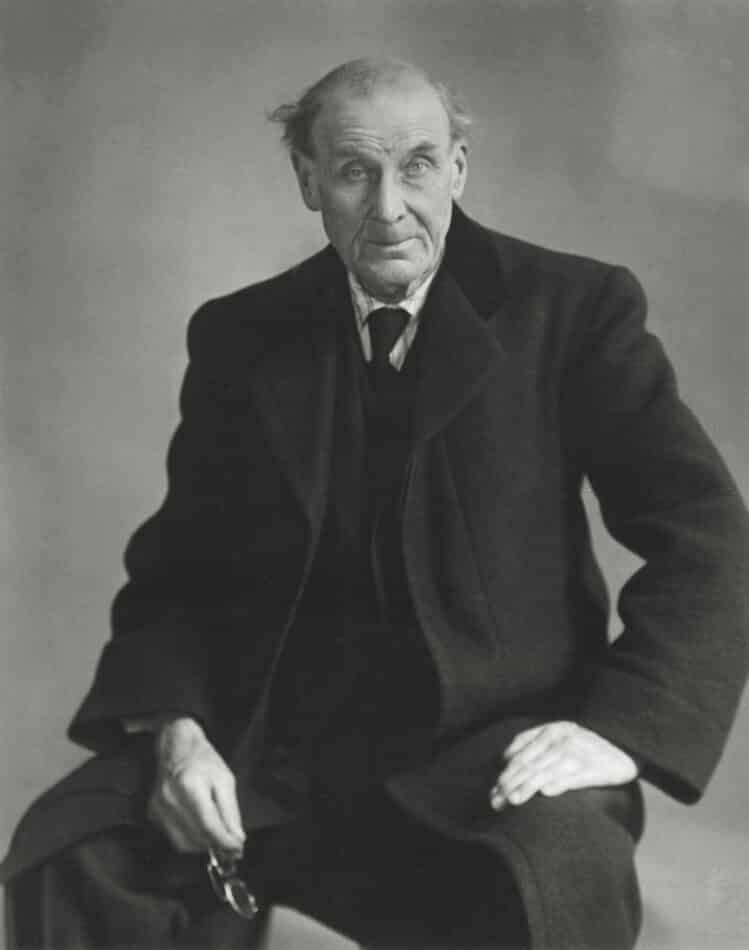

As Sylvia Beach, the proprietor of the fabled Paris bookstore Shakespeare and Company, wrote in her memoir, “To be ‘done’ by Man Ray and Berenice Abbott meant you rated as a somebody.” For Abbott, the most important somebody to come to her Paris studio was an elderly nobody named Eugène Atget, the now legendary documentarian of vieux Paris. She’d been introduced to him by Man Ray.

Atget’s stately, richly evocative pictures of old shop windows and street scenes influenced the Surrealists, but they thoroughly transformed Abbott’s vision and the course of her life. He died not long after he sat for her. The following year, 1928, she scraped together the money to purchase the bulk of his archive, becoming the chief custodian and promoter of his legacy.

Atget’s pictures inspired Abbott’s remarkable documentation of the fast-changing New York of the 1930s. They were also seminal for other celebrated photographers of her generation and the following one, from Walker Evans to Lee Friedlander — even Deborah Turbeville.

Ansel Adams deemed Atget’s prints “perhaps the earliest expression of true photographic art.” It’s sobering to consider that if Abbott had not salvaged and promoted this trove, photography might have taken an entirely different course. Few artists have the spirit and fortitude to be both passionate preservers and bold innovators. Abbott was among those few. And with this new book, her reputation should loom large.