This photograph of Eileen Gray was taken by Berenice Abbott in 1926. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland

The life of Eileen Gray (1878–1976) is inspiring, but also sad. She was a brilliant designer, yet because she was a woman and bisexual, her extraordinary achievements came at great personal cost. In fact, for much of her life, she lived and worked in complete obscurity. Today, some 40 years after her death, she is recognized as one of the most influential designers of the early 20th century, a singular visionary, largely self-taught, who helped shape both the Art Deco and modernist movements, endowing them with a distinctly feminine sensitivity and wit.

Gray’s background was as unusual as she. Her father, James McLaren Smith, was an Anglo-Irish landscape painter and her mother, Eveleen (Pounden) Smith-Gray, was a Scottish aristocrat. Bookish and shy, Katherine Eileen Moray Smith, as she was christened, was the youngest of the couple’s five children. When she was 10, her father left the family to live in Italy and paint. And for the rest of her childhood, she and her siblings divided their time between the family estate in Enniscorthy, Ireland, where she was born, and a townhouse in London. In 1895, after the death of her maternal grandmother, Gray’s mother became Baroness Gray and changed the surnames of her children accordingly. Eileen became a “Right Honorable” but never used the title as her politics were pointedly left of the peerage.

Gray remained devoted to her father despite his having abandoned the family. He had recognized her artistic talent early and took her with him on painting jaunts to Italy and Switzerland. Later, he encouraged her to study at London’s Slade School of Fine Art. So she was left bereft in 1900, when her father died, as did her youngest brother, killed in the Boer War. Perhaps to assuage their mutual grief, her mother took Gray to Paris that year to see the World’s Fair, and there she became enamored with the city and all things daring and new, especially the displays of Art Nouveau furnishings and the designs of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Her passion for design had been sparked.

After graduating from Slade, in 1902, she continued her training in Paris. Gray adored the city for its beauty and sophistication, as well as its bohemian culture. She could be herself in Paris, in a way that she could not in London, much less Ireland. She mingled with the city’s glittering circle of lesbian expats and embarking on a long, on-and-off affair with the celebrated singer Damia. However, unlike many in this group, she remained relatively discreet about her associations (and dutiful to her aristocratic family). When her mother became ill in 1905, Gray returned to London to look after her.

One day while strolling in London’s Soho, she came upon a lacquer repair shop and became fascinated by the Asian screens inside, as well as the whole process of making them. Soon, she apprenticed herself to the shop owner. When she returned to Paris the following year, he put her in touch with a young Japanese lacquer master, Seizo Sugawara, with whom she would study for the next four years. After she became proficient in the techniques, she experimented on her own for another three years, until she felt her designs were original enough to show.

While she was devoted to becoming a master of her craft, Gray also involved herself in other creative projects and adventures. In 1909, she traveled to Morocco with her friend, the weaver Evelyn Wyld, where she learned from local craftswomen how to dye wool and weave. During these years, she also learned to pilot a plane and was one of the first Parisians to obtain a driver’s license.

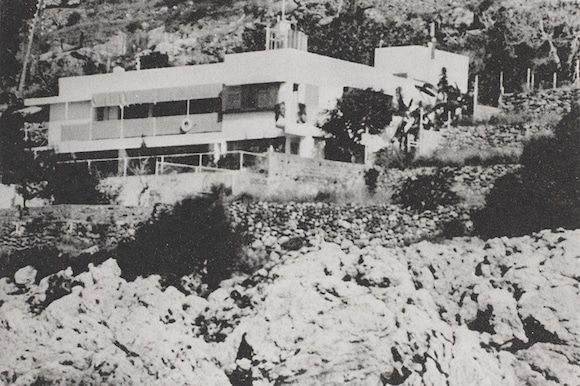

In 1926, Gray designed this vacation home, called E-1027, located in the South of France, to share with Jean Badovici.

When she finally presented a screen and several other decorative panels at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in 1913, at the age of 35, they created a sensation. Jacques Doucet, a leading haute couturier and a famously adventurous art collector, acquired the screen and commissioned other lacquer works. One of those pieces was her first masterpiece, a screen she called Le Destin, featuring an allegorical scene on one side and a geometric design on the other. The work so impressed Doucet he insisted she sign it, which she never did again. He also asked her to add tassels with large amber beads to the black lacquer and gilt Lotus table he had commissioned, which she did, but always regretted as being too gaudy.

Nevertheless, thanks to Doucet’s patronage, Gray became a darling of the beau monde. And upon her return to Paris at the end of World War I, much of which she had spent in London, Gray received her first interior-design commission from high-society milliner Suzanne Talbot. Her renovation of the Rue de Lota apartment would go on for a number of years. In addition to conceiving almost all the furnishings, including the lighting and carpets, Gray covered the molded walls of the entry with movable lacquered panels, which anticipated her now iconic Brick screen, and hand-woven textiles in another. In photographs of the rooms, you can see her style evolving from a theatrical Art Deco in pieces like the Dragon armchair to cleaner, yet still highly personal designs such as the Michelin Man–inspired Bibendum chair, which demonstrated that tubular steel seating could be sleek and comfy.

Almost all the furniture she designed for Talbot is now legendary, including the sumptuous Pirogue day bed in brown lacquer and silver leaf, inspired by a dugout Polynesian canoe, and the lounge-worthy Lota sofa. Spicing these sophisticated splendors with some “savagery,” as was then the vogue, she threw zebra skins and other exotic pelts over the floors and furnishings and adorned the rooms with tribal art. Yet what is most distinctive about the apartment, and what seems so characteristic of Gray, are the little functional details: the way, for example, that the hat shelves and closets in the dressing room are attractively lit, while the shoe cubbies are hidden; the space-saving swiveling drawers under the curved counter in the bathroom, where an elegant Satellite mirror illumines the user while providing an adjustable magnifying mirror.

By the time the Talbot apartment was completed and deemed a triumph, Gray had opened a shop called Jean Désert, where she displayed her furnishings and carpets alongside work by her artist friends. It quickly become a hangout for just about every glamorous person living in Paris, from the Vicomtesse de Noailles to James Joyce. Gray’s highly original designs garnered praise from influential architects, too, including Le Corbusier, Robert Mallet-Stevens and the Romanian-born practitioner-turned-critic Jean Badovici. Although flattered when Corbu and Mallet-Stevens invited her to collaborate, she declined. But when Badovici championed her work, she fell madly in love with him. He helped convince her to turn her talents to architecture, and she never looked back.

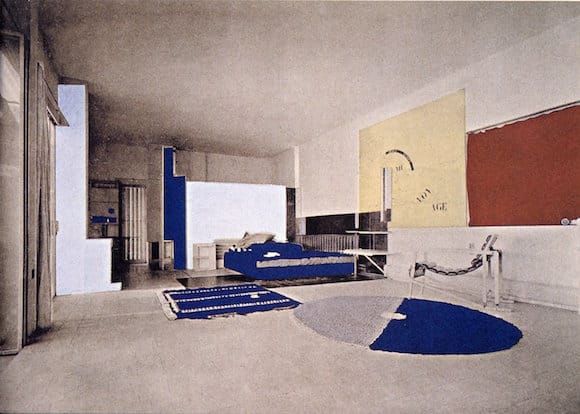

This colorized vintage photo shows the Salon, or living room, of Villa E 1027, where the furniture and rugs were designed by Gray.

In 1926, when 48, she embarked on the design of a vacation house for herself and Badovici on a hillside in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, in the South of France, that would be all about the sun and sea. While the design was all hers, Badovici provided technical assistance. The house she conceived was a true love nest, as was expressed in its deeply romantic, if cryptic, name E-1027. The “E” was for Eileen, while the “10” and “2” signified the placement of Badovici’s initials in the alphabet and likewise the “7” stood for “G.” Everything about the design was highly considered, not so much for architectural impact, but for the joy of living. “A house is not a machine,” she would later write as a retort to Corbu’s famous quip. “It is the shell of man — his extension, his release, his spiritual glow.”

A modest box-shaped building, on pillars, E-1027 guides the visitor from the entry on the hillside to the terrace overlooking the sea. To signal that this was a home for relaxing, in the entryway, Gray scribbled entrez lentement (enter slowly) on the wall, as well as other whimsical graffiti all about, revealing an almost giddy joy in this cohabitation. Her plan allows the landscape to seemingly wind through the house, while inside fixed and freestanding walls gracefully provide private spaces for retreat around an open plan.

Yet again, there is much genius in the details. In the master bedroom, for example, there is a narrow window to maintain privacy while providing a view of the sea from the bed. A winding glass and steel stairway to the second floor resembles a nautilus shell. Many of the ingenious furnishings Gray specially concocted for the house have become modern classics, none more famous than the adjustable E-1027 side table in glass and tubular steel.

Alas, the couple did not live happily ever after in this exquisite home, which drew wide praise when finally published in 1929. Three years after its completion, they split up. Apparently, Badovici was too much of a party boy. But, ever generous, Gray gave her ex-lover the house. A number of years later, he invited his friend Le Corbusier to stay at E-1027, which had been inspired by his architectural theories, and for reasons that can only be speculated upon, Corbu painted eight wildly provocative Picasso-style murals in garish colors on its white walls, forever destroying its serene and delicate charm. Gray was furious. But, as was her way, she refrained from publicly chastising the modernist master. (By then, she had built Tempe à Pailla, a small but equally inventive villa for living and working in nearby Menton.) Instead, she focused her energies on her new passion for designing social housing. Unfortunately, none of her projects were ever realized due to the onset of World War II.

Gray was forced to leave the coast and live in the interior of Provence for much of the war. When she returned after the war, she discovered that Tempe à Pailla had been ransacked, with all her drawings and plans destroyed. E-1027 had also been left badly damaged, although she must have taken some pleasure in noting that German soldiers had used Corbu’s murals for target practice. Even more disturbing was that in the years that followed, the design of E-1027 was attributed not to Gray, but to Badovici. Some have credited Le Corbusier with this misattribution. And as Gray fell further into obscurity, many of her furniture designs were actually credited to Corbu. Still, Gray continued to work quietly in her Paris apartment on a new retreat she’d designed for herself in St. Tropez. When architectural projects dried up, she wrote poetry, conceived sets for an Irish epic — she remained an Irish nationalist — and returned to painting.

Then in 1972, when she was 94, Jacques Doucet again brought Gray fame. At the Christie’s sale of his art and furnishings, Yves Saint Laurent bought the Le Destin screen for $36,000, a staggering sum at the time. No one was more shocked than Gray. And then the following year, the London design retailer Zeff Aram asked her for the rights to reproduce several of her designs. He later recalled how she demurely asked him: “Do you think it’s worthwhile to do?” Gray may have been uncertain, but Aram noted that she was meticulous about checking all the details in his reproductions.

By the time Gray died at age 98, in 1976, she had finally been acknowledged as an early modern master. And when Christie’s put Yves Saint Laurent’s art and design collection on the block in 2009, her Dragon chair sold for $28.3 million, a new record for a piece of 20th-century furniture.