Elsie de Wolfe was a self-pronounced “rebel in an ugly world.” Her revolt began early, when as a small girl she threw a temper tantrum at the sight of the hopelessly drab William Morris-style wallpaper with which her mother had covered the walls of her room. Born in New York, in 1865, to a doctor and his wife, she lamented growing up amidst the dark, brooding and heavily ornamented rooms of her family’s Victorian brownstone, despite the fact that such decor was then considered the height of fashion. Even at a young age, de Wolfe had decisive ideas about design, and she resolved to make it her life’s mission to surround herself instead with beauty. It was a calling that would reward her with fame, fortune and lasting renown as “the mother of interior decoration.”

A 1925 image of Elsie de Wolfe. Apart from interior design, de Wolfe loved flowers, small dogs and couture clothing.

As a young woman, de Wolfe participated in amateur theatricals, a favorite Gilded Age pastime. Through this circle met Bessy Marbury, who became her devoted lover and mentor for the next 40 years. Nearly a decade her senior, Marbury came from a rich and prominent New York family and had already trail-blazed a new profession as a literary agent and theatrical manager, with Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw among her clients. Not long after their relationship began, De Wolfe’s father died, forcing her to earn a living; Marbury helped de Wolfe secure work as a professional actress.

Neither a beauty nor a talent, all de Wolfe had going for her as an actress was a petite, willowy figure ideally suited to the fashions of the day. She made the most of this asset, however, traveling to France every summer with Marbury to select outfits from top Parisian couturiers to wear in the next season’s productions. Captivated by her fetching outfits, female theatergoers began ordering the same styles or having them copied, turning De Wolfe into a fashion leader. Years later, in 1935, she was voted the best-dressed woman in the world.

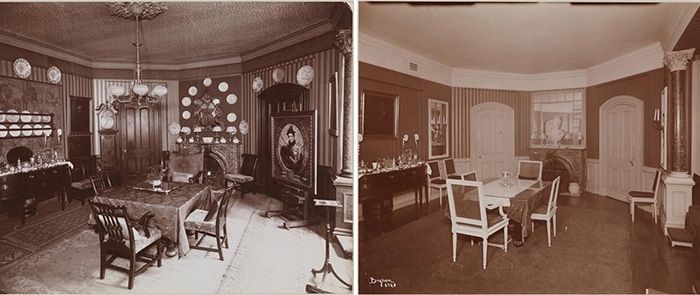

Marbury and de Wolfe’s living room before (left) and after (right) de Wolfe’s “refreshing.”

During these trips, de Wolfe became enamored with the architecture and interior design of the 18th century, even though the style was considered hopelessly passé. De Wolfe came to see in these interiors the very qualities that she found wanting in Victorian décor, namely light, air and comfort. Now sharing a home with Marbury, de Wolfe was encouraged by her partner to use the space as a canvas for her ideas about interior design. The dark woodwork, heavy curtains and clunky furniture of their home were replaced by de Wolfe with luminous ivory and pale gray walls, light muslin curtains, an abundance of mirrors, floral upholstery and pale painted Louis-style furniture. The new look caused a sensation among their society friends, including the likes of Wilde and Sarah Bernhardt, Stanford White, and J.P. Morgan’s daughter, Anne. Requests for de Wolfe’s decorating counsel quickly followed, enabling her to abandon acting for good.

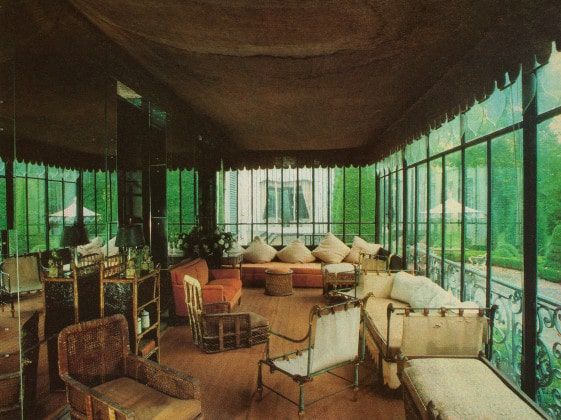

This photograph of the completed Trellis Room in the Colony Club caused a sensation among the press.

Her big break as a “professional decorator” came in 1905, when she was asked to decorate the rooms for The Colony Club, the first women’s clubhouse in America, which was being designed by Stanford White. Considered a radical project at the time (the socialite founders were mostly suffragettes), de Wolfe created a suitably revolutionary décor. The walls were pale, the floors tiled and the rooms filled with glazed chintz upholstery, then used only in country houses. The room that most dazzled visitors was an indoor garden pavilion furnished with wicker chairs that featured trelliswork on the walls and ceiling, interwoven with ivy and lights to approximate filtered sunlight. The startling originality of the design won de Wolfe numerous lucrative commissions and the acclaim of the national press.

The sunroom at de Wolfe’s Versailles residence, Villa Trianon.

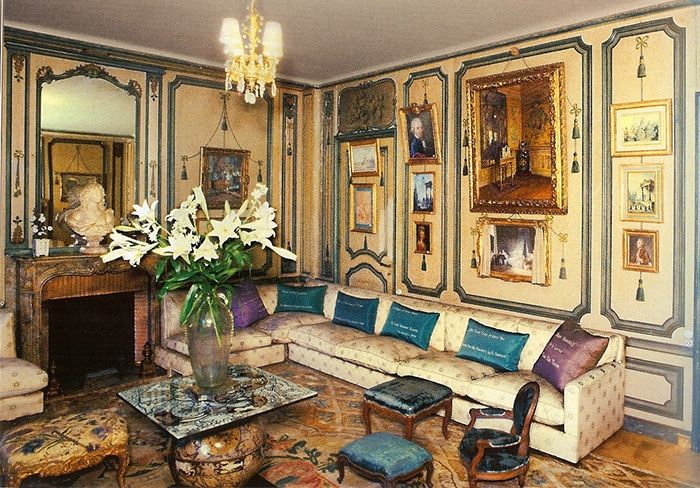

Around this time, de Wolfe and Marbury purchased Villa Trianon, at Versailles, an 18th-century wreck that de Wolfe transformed into a dreamy evocation of life in the age of Louis XV. The house became a lab for her decorating ideas for the rest of her life, as well as a favorite hangout for the period’s international glitterati: Noel Coward, Elsa Maxwell, Cecil Beaton, Coco Chanel, and Douglas Fairbanks. As Wallis Simpson, observed, “She mixes people like a cocktail — and the result is sheer genius.”

As her fame grew, de Wolfe was enlisted to write a column on domestic style for an early women’s magazine; her counsel ranged from how to select an apartment to simple do-it-yourself projects. De Wolfe believed that everyone, no matter their background, could create a delightful room “where the colors blend and the proportions are as perfect as in a picture.” Good taste was as important as good manners, she advised her readers, since “you will express yourself in your home, whether you want to or not.” The articles were later collected and published in the bestselling 1913 book The House In Good Taste.

De Wolfe designed this room as Mrs. Frick’s boudoir. The space was known as the Boucher room for the eight panels that adorned it 18th-century painter François Boucher.

By now a household name and a celebrated authority on not just decorating, but lifestyle, de Wolfe was approached by Henry Clay Frick — the wealthy industrialist and avid art collector — to decorate his family’s new quarters in the beaux-arts mansion he was building on New York City’s Upper East Side. Frick agreed to pay de Wolfe a percentage of the cost of everything she acquired for the 14 rooms, from domestic necessities to important 18th-century antiques. The compensation agreement they struck made her a wealthy woman and has since become a standard in the industry.

Despite her success, de Wolfe was not without a social conscience. When WWI broke out, she returned to France and became a Red Cross nurse, turning her villa into a hospital for gassed soldiers. At the end of the war, during the Versailles Peace Treaty talks, she rather incredibly entertained most of the signatories there. For her devoted service, France later awarded her the Croix de Guerre.

De Wolfe’s private sitting room at Villa Trianon. The pillows are embroidered with her aphorisms: “Never explain, never complain” and “I believe in optimism and plenty of white paint!”

A new age arrived with the end of the war, and the ever-youthful de Wolfe — who was still known to stand on her head at parties and rinse her silver hair blue or green to match her jewels — immediately embraced its possibilities. Her style became more free and eclectic. She mixed animal prints with Chinoiserie; added Regency and Chippendale to her stylistic repetoire; employed jazzier black-and-white schemes; and became enamored of the color beige. Reputedly, when she first saw the Parthenon, she exclaimed “It’s beige! My color!” Her business flourished, but she personally focused only on such tony clients as Cole Porter and Condé Nast.

According to de Wolfe, animal prints belonged alongside French antiques.

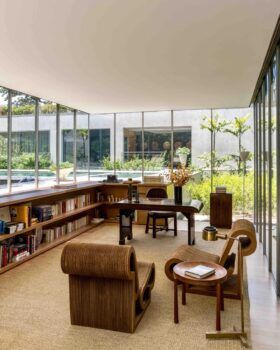

In the late 1930s, de Wolfe decamped to Beverly Hills to wait out WWII. There, she purchased a Hispano-Moorish house that she dubbed “After All,” and used as a party place stage set for entertaining prospective clients. She decorated the house in a fresh palette of white, black and emerald green, with coral red accents. To make the gardens feel larger, she discretely set up outdoor mirrors. Many of the home’s most whimsical, baroque furnishings were made by Tony Duquette, a young artist she’d discovered at a Hollywood dinner party, who would go on to become a design legend in his own right.

The drawing room of de Wolfe’s Beverly Hills estate, After All.

During WWII, the Nazis annexed de Wolfe’s precious Villa Trianon, and then it was occupied by General Eisenhower and the Allied Command. When she finally regained control of it two years after the war’s end, it was in derelict condition. She spent the last four years of her life returning it to its former glory.