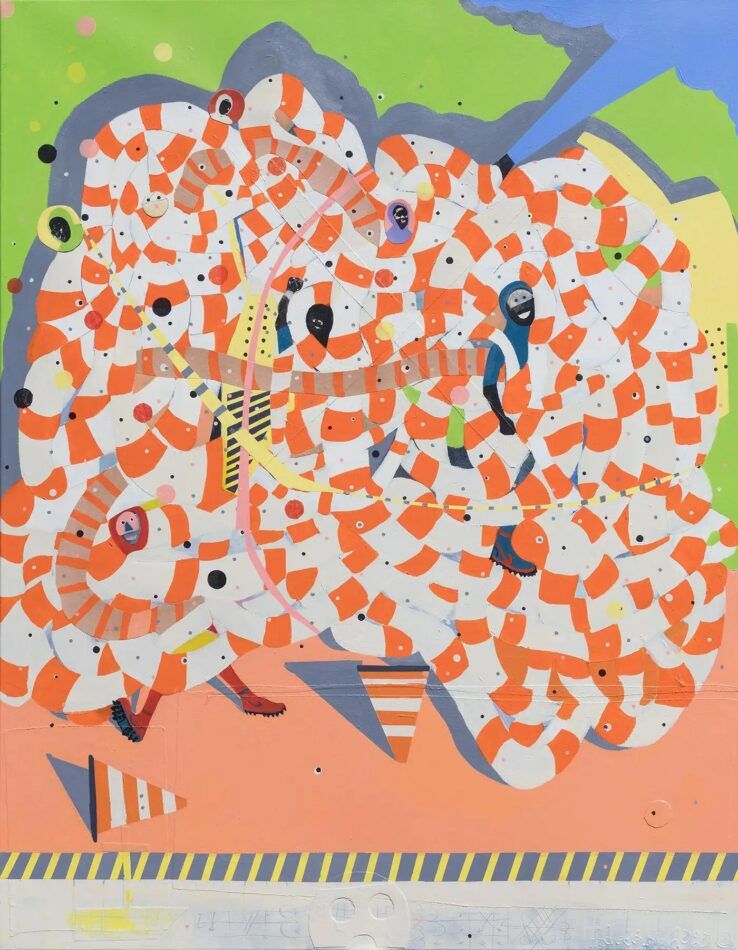

Sometimes a picture is, in fact, worth a thousand words. Such is the case with Francks Deceus’s Mumbo Jumbo #5. In this five-by-four-foot canvas, painted in 2000, the Brooklyn-based artist has encapsulated his experience navigating life in New York City as a Haitian immigrant growing up in the 1980s and ’90s.

“It was chaos and confusion and energy and flux and coming and going and hustling and bustling,” says Deceus. We feel all of that here.

Deceus tells his story with the help of a lithe, athletic figure he calls Cappy, an alter ego named for Cap-Haïtien, the Haitian town he and his family left for Brooklyn in the late 1970s, when he was nine years old. Here, we see several versions of Cappy entangled in a network of high-pressure fire hoses along with construction cones and other allusions to barriers.

The fire-hose motif recurs across Deceus’s “Mumbo Jumbo” series, referencing notorious law-enforcement tactics used to punish peaceful Civil Rights–era demonstrators. “It’s a reference to human rights and the limitation of movement for a large swath of the population, from the Mayflower to the present,” explains Deceus. “But despite this hurdle, this character has still managed to find his individuality, his sense of purpose, his humanness. So you see this bursting of energy and possibility and exhilaration.”

Indeed, Cappy, with his broad smile, is not deterred but resilient. “My parents had education and degrees that had no significance here in terms of gaining secure employment. So, they got blue-collar jobs. It was a matter of survival — but also perseverance and what happens when barriers and obstacles are replaced with opportunity.”

“There is a refreshing joyfulness to Francks’s work,” says Valentina Puccioni, of New York’s Arco Gallery, who included his paintings in a show of Caribbean art co-organized with Anderson Contemporary in the Financial District. “He always leaves room for optimism, even though his experiences may have been full of frustration.”

Deceus cites African American abstractionists Howardena Pindell, Norman Lewis and Ed Clark, among others, as influences. His style also calls to mind children’s book illustrations, with his muted but juicy hues and crisp blocks of color and the simplified features of Cappy, who comes across as a kind of urban superhero. It’s easy to imagine the impression the chaotic city made on the artist as a child. But this is clearly the work of a sophisticated artist adept at a variety of techniques.

Before Deceus starts painting, he builds up his surface by layering strips of canvas. The process creates a tactile sense of the city’s density and dynamism and captures a sense of the scrappy DIY survivalism of his family’s early days in New York. He may also add collage elements, like silkscreened photographs, which suggest memories of relatives or friends who made their way in and out of his life. “Over the years, we probably had a dozen family members stay on our cot until they got on their feet,” recalls the artist. “As a kid, you don’t know the details, but there are always these kinds of stories in the back of your mind.”

Deceus drew several Haitian Vodou cosmograms, or vèvès, across the bottom of Mumbo Jumbo #5. They stand as a reminder of his family’s culture but also of their marginal identity in New York as Black but not African American. The title, meanwhile, refers to the 1972 novel Mumbo Jumbo, by African American writer Ishmael Reed, set in Harlem in the 1920s. “It’s a way to bridge these two experiences — past and present, Haiti and America — and to link back to Africa and make a broader visual dialog,” Deceus says of his layering of symbolic and allegorical references. “I’m not a very literal storyteller.” As it turns out, his work is all the more powerful for it.