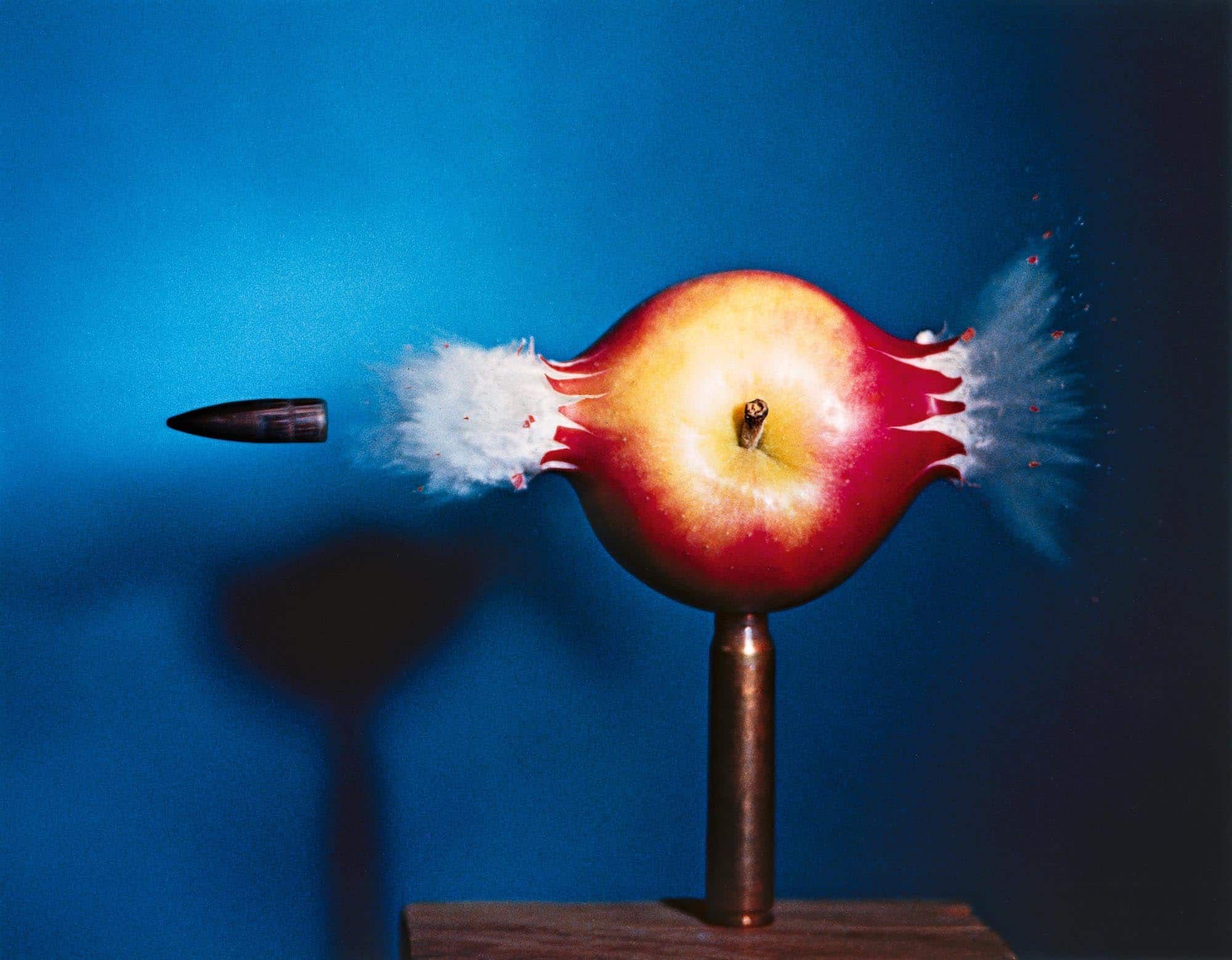

Bullet through Apple, 1964, by Harold Edgerton. © 2010 MIT. Courtesy of MIT Museum

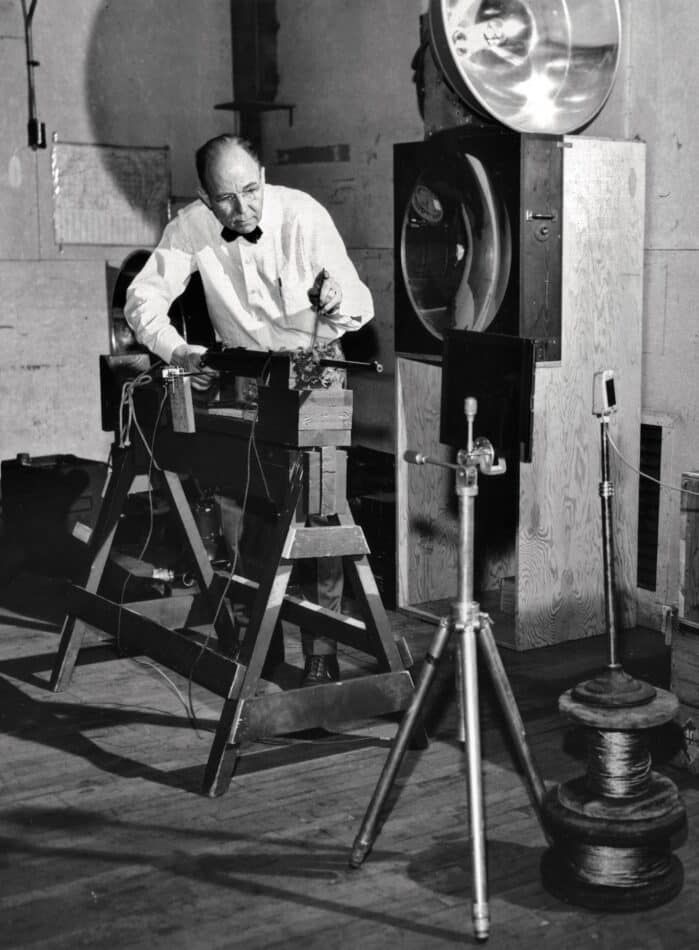

The photographer Harold Edgerton (1903–90) preferred not to call himself an artist. He described his career in pragmatic, matter-of-fact terms: “I am an electrical engineer and I work with strobe lights and circuits and make useful things.”

This modest brief doesn’t do justice, however, to Edgerton’s contributions to the history of photography, which include the invention of the modern electronic flash and a related body of work that expands our perception and understanding of time and motion.

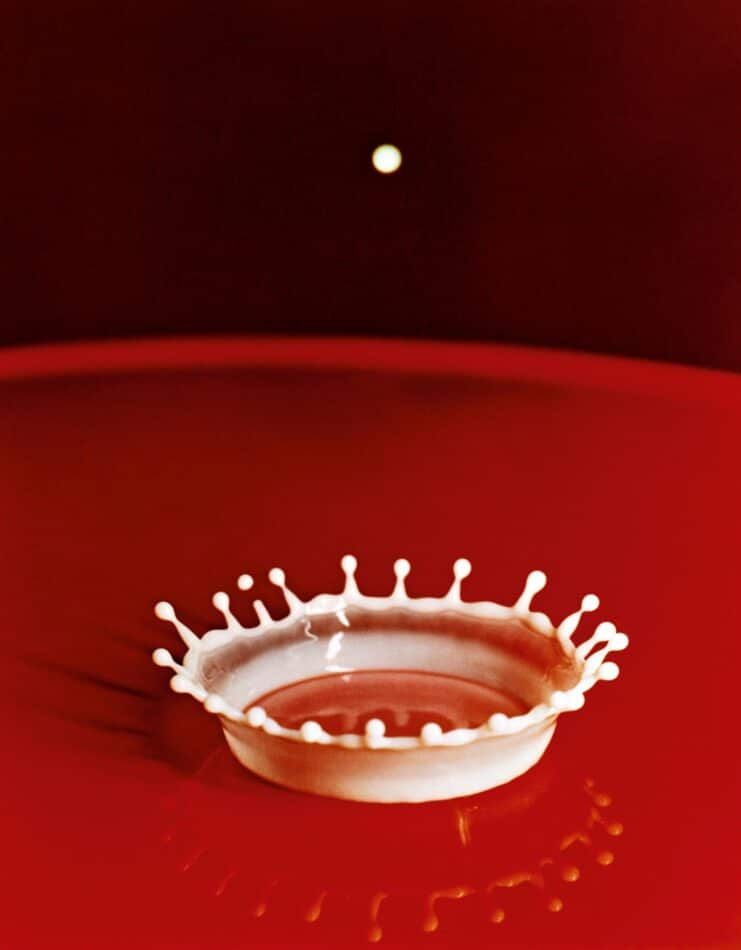

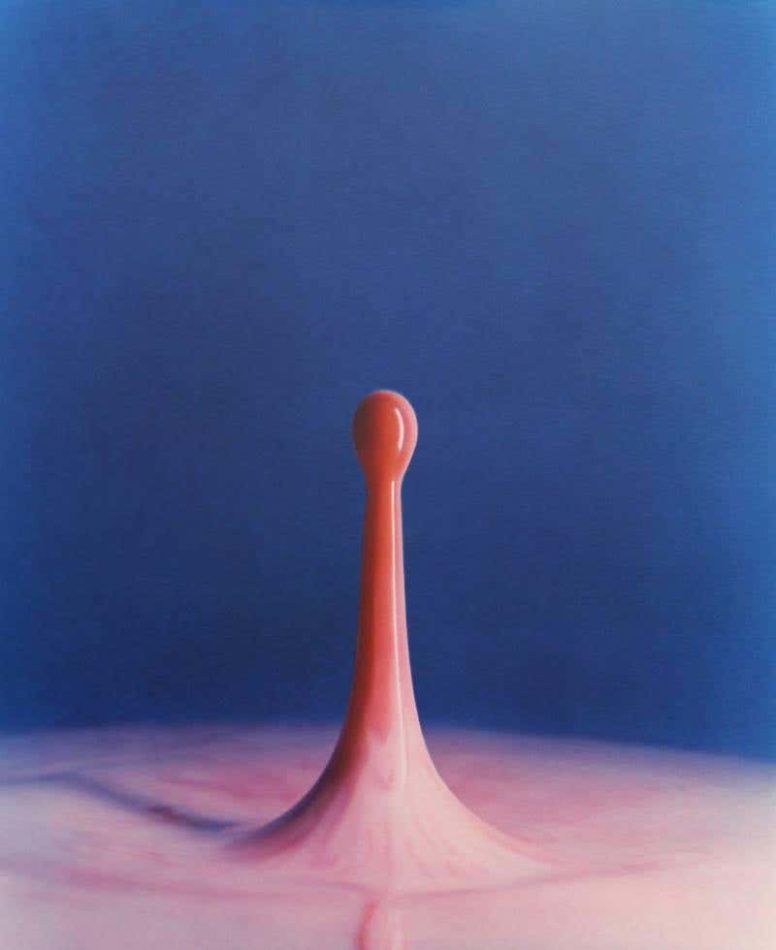

His most famous photograph, Milk Drop Coronet, captures the fringed ring, or “crown,” formed when liquid splashes on a flat surface — a phenomenon too brief to be seen with the naked eye.

With a carefully honed choreography of droppers, timers and stroboscopic lights, he made many versions of this image over more than two decades. An endlessly fascinating color example from 1957, in which the milk bounces off of a red table, was selected by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential photographs of all time and now graces the cover of the book Harold Edgerton: Seeing the Unseen (copublished by Steidl and the MIT Museum, in Cambridge, Massachusetts).

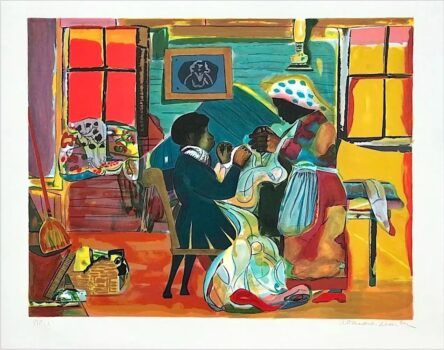

In other experiments with strobes and stop-motion photography, Edgerton showed bullets piercing apples, balloons and sheets of plexiglass; light bulbs and coffee cups shattering the instant they hit the floor; and little wisps of smoke spiraling off the blades of a fan.

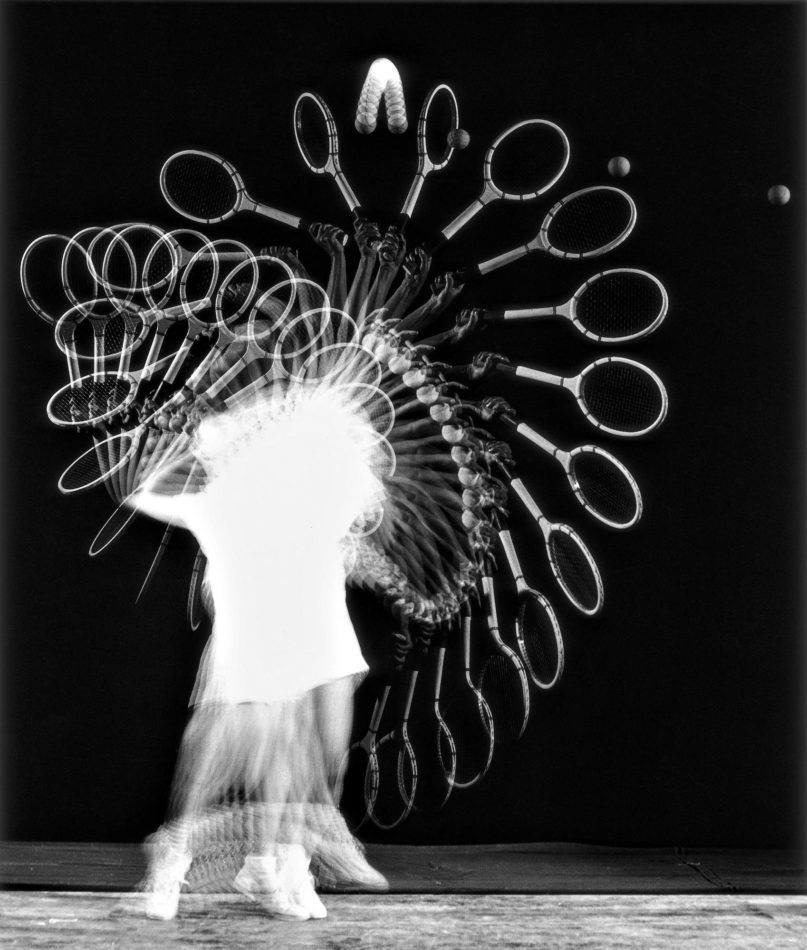

The technologies he pioneered had applications in many fields, from sports (analyzing golf swings, tennis strokes, pole vaults) to the military (assisting the U.S. Army Air Force in its aerial reconnaissance during World War II, an activity that earned him the Presidential Medal of Freedom). In the postwar years, he became involved with Jacques Cousteau’s underwater expeditions and developed sonar devices for use in maritime research and archeology.

The Nebraska-born Edgerton was known as Doc to students and faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he obtained master’s and doctoral degrees in electrical engineering and remained as a professor and researcher until the end of his life. Harold Edgerton: Seeing the Unseen includes many of his notes and diagrams, emphasizing that his photographs are experiments as well as artworks.

Although Edgerton may have seen himself as a scientist first and foremost, influential figures in art and photography consistently praised the beauty and modernity of his photographs. He received a bronze medal from the Royal Photographic Society in London, where he showed frequently.

Further adding to his artistic bona fides, he was included in the earliest exhibition of photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, organized by the pioneering curator Beaumont Newhall in 1937. “No eye has ever seen the form of a drop of milk splashing,” Newhall wrote in the accompanying catalogue.

Another famous MoMA photography curator, John Szarkowski, later wrote, “Although Edgerton’s basic motive has been informational, not aesthetic, he has consistently made pictures that have been bold, stylish and dramatic.”

Anyone looking at images such as Cranberry Juice Dropping into Milk, in which the action described in the title results in a spiky, multicolored protuberance of a backsplash, would have to agree.