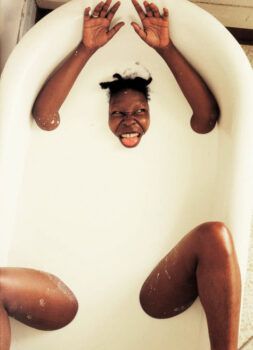

Cuba, 2017

In 1972, while Jean-Francois Rauzier was a young man of 20 just finding his way in the world, he helped his uncle, a part-time photographer, develop black-and-white film in the darkroom. “When I saw the image emerge, it was like magic,” he recalls. “Yet it also rendered reality. I was hooked.” He went off to study at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure Louis-Lumière and for nearly 30 years enjoyed a successful career as a commercial photographer.

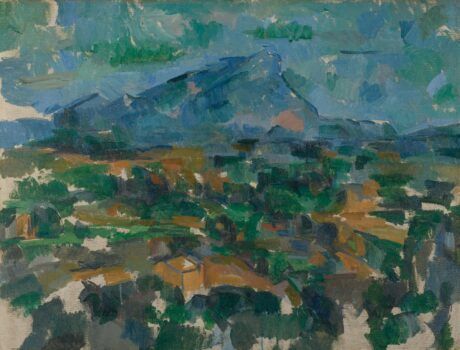

All the while, Rauzier was also working on more personal photographic expressions. Yet he didn’t make a true artistic breakthrough until 1998, when traveling in Tuscany. The landscape enthralled him. “The vistas were so wide!” he exclaims. “I thought they were fabulous.”

They were, in fact, so expansive he couldn’t capture them as he wanted with a wide-angle lens. So Rauzier, inspired by David Hockney’s composite photographs, began shooting multiple pictures of the rolling hills and fields to a form a panoramic image. After successfully stitching the vista together digitally, he thought, Why not use two or three lines of images to expand the view?

Those experiments eventually led to the mosaic-style photographs, composed of up to 3,500 individual images, he now calls “hyperphotos.” He produces these works in editions of eight C-Type prints, Diasec-mounted on aluminum, with each print featuring a unique detail.

The 1990s were a decade when a number of photographers, especially such now-celebrated German lenspersons as Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth and Candida Höfer were exploring the possibilities of digital manipulation in large-scale photography. Through the hyper reality of immense prints, often up to 10 feet wide, they were seeking to reveal the peculiar actualities of our contemporary existence. In the beginning, Rauzier says he was often compared to Gursky. “I love Gursky’s work,” he says, “but he is very Protestant in his vision, while I am Catholic. I love to put a surrealistic slant on my images to show life in all its immense complexity.”

“His artistic exploration and vision take the viewer’s impression of what is reality to another level,” says Sandra Waterhouse of Waterhouse Dodd gallery, which represents Rauzier in New York and London. When she first saw his work in Paris, she was so taken with it that she sent her Parisian agent on a mission to track him down. “The traditional purpose of photography was to record our memories faster than painters, and with an exact reproduction of scenery and people, as they are made to witness the moment and time,” she says. “Rauzier’s creations, by contrast, transform the world according to his dreams, wishes and anxieties, and recreate the magic and secrecy of ancient legends and stories, using 21st-century media.”

Cuba, Callejon de Hamel, 12017

Urban realms and monumental architecture are continuing sources of inspiration for Rauzier, yet he also draws deeply from the great canon of Western art history and literature. He cites, for example, the post-modernist French novelist Georges Perec as a major influence. The rules-based structure of Perec’s 1978 novel La Vie mode d’emploi (Life a User’s Manual), which explores the lives of the inhabitants of a fictitious Parisian apartment house by moving around the building’s floorplan like the knight on a chessboard, helped Rauzier conceive his stunning 2015 series of transfigured buildings, which he dubbed “Babel.” Two of the images, one of buildings in Paris and the other New York, also pay homage to Bruegel’s fabled painting of the biblical tower.

Travel is central to Rauzier’s creative process. After choosing a destination to serve as the subject of his next project, he reads all he can about the place, but arrives without any notion of what image he’ll create. Instead, he snaps thousands of images of everything he encounters: landscapes, buildings, flora and fauna and whatever else catches his fancy. He shoots from all angles and often as close as possible. “I shoot very fast,” he says. “I don’t really see what I shoot. It’s only later I see and find the picture.”

When reviewing his cache, he’s often surprised at what most fascinates him. When he visited Los Angeles, it was the “fabulous trees” that most impressed him. “That’s not what I read about in books,” he explains, laughing. “That’s why I love photography and this process. You discover things you don’t expect.”

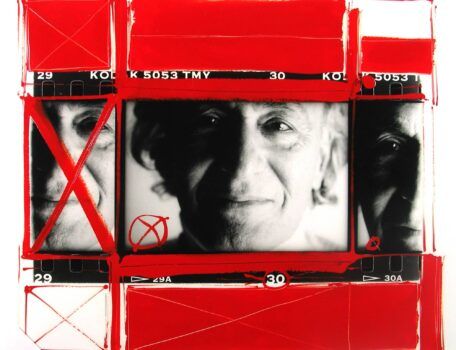

Babel Kircher, New York, 2015

Once he “sees” what he wants the image to be, he uses software to flatten curved lines and straighten awry perspectives, to duplicate and distort objects and to add elements from his immense stock library. While the process is digital, the resulting image is painterly in its references and subjectivity. As Rauzier has quipped: “It’s a kind of absolute power over the world!”

So dense and complicated are some of the prints that new details can be discerned years after a collector has acquired a work. It’s this endless sense of discovery that makes his creations so captivating. See for yourself at “Hyperphotos,” Waterhouse Dodd’s pop-up gallery at 1070 Madison Avenue in New York. The show, which runs through November 18, features 26 fantastical works composed of images from New York, Cuba and France, as well as a couple of brilliant renderings of Brasilia in the style of the paintings of Fernand Léger, who influenced many Brazilian artists.