Whoever said “Don’t judge a book by its cover” hasn’t seen the new valedictory volume Michael Coffey: Sculptor and Furniture Maker in Wood. Pointed Leaf Press managed to give the book a wrapper almost as tactile as the furniture Coffey has been carving out of bubinga, Mozambique and padouk wood for nearly 60 years.

As a maker, Coffey has few peers. Joseph Walsh and Wendell Castle come to mind, but Coffey’s designs, with surfaces as distinctive as fingerprints, are always recognizable as Coffeys. Honestly, if you’re not obsessed with this man’s work, you haven’t been paying attention.

Rectilinearity is “boring, static and without feeling,” he writes in the new book. “In my work I borrow the curving line from nature because it conveys emotion — excitement, tenderness, danger, whimsy. It speaks of movement, like flowing water or a running animal. It is going somewhere.”

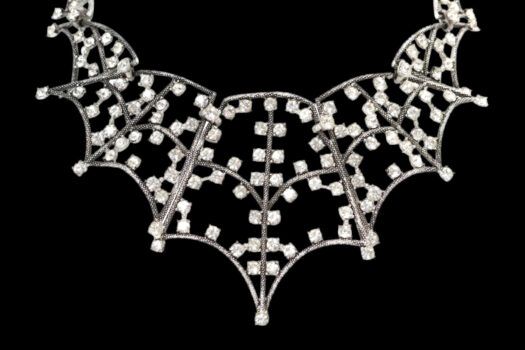

That certainly describes his 1982 Satan’s Tongue table, offered by New York’s Maison Gerard. (This Satan’s Tongue is the first of several similarly named pieces. It’s the only one, Coffey says, that he made of padouk, a tropical wood known for exceptional stability.) The piece is a single swoop: a tongue or a serpent or a flying carpet.

“I think what’s special about it is that the cantilever is defying gravity, and that creates a tension,” Coffey says. “It looks like it’s going to fall, but” — because he was careful to make the base heavier than the top — “it doesn’t.”

The table is “whimsical, and it flows with the grain,” observes Benoist Drut, of Maison Gerard. “Michael knows wood like nobody else, and he lets the wood do what it wants to do.”

Growing up at the end of a rutted dirt road in Pennsylvania during the Great Depression, Coffey learned a few things, including how to make his own toys and how to appreciate nature. Now living in Western Massachusetts, he’s still making his own toys, though he is happy to share them with discerning and patient collectors.

“When you commission a piece from him, he really puts everything into it,” says interior designer Amy Lau, who has several custom Coffeys in her New York apartment. Each piece can take a month or more to make, with Coffey acting as both engineer and artist.

His drawings, which he transfers from paper to the raw lumber in crayon, demonstrate the amount of forethought each project requires. “Before I cut a piece of wood, I know exactly what I’m going to do and how I’m going to do it,” he says.

No one who knows Coffey agrees with his description of himself in the new book: “a stubborn, quixotic old codger.” Old, maybe, but at 94, he is “jolly and a lot of fun,” says Lau. And incredibly productive. Although he can no longer do much physical work, he goes into the studio every day, where he supervises two longtime assistants and where, he says, he’s “still the arbiter of quality.”